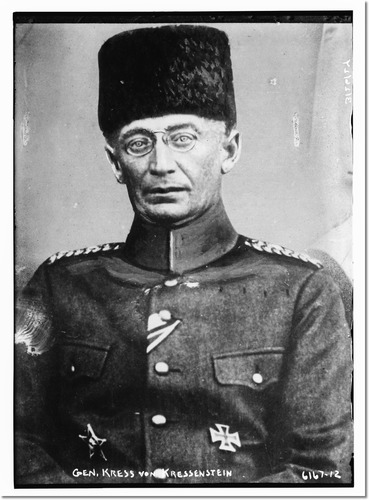

Baron (Freiherr) Kress von Kressenstein, 1916

Disabled British Mark I female tank at the Second Battle of Gaza

An strategic misstep occurred when the Ottoman General Staff appeared to underestimate the importance of the Sinai-Palestine front and the risk of a constantly growing British military presence, which was forming into an expeditionary force while the last strategic reserve was expended irresponsibly on the Caucasus front and in Europe. Most probably, in addition to its inborn myopia to see the strategic picture, the early Ottoman victories at very low cost in the Sinai and the slow British buildup deceived the General Staff. The Sinai-Palestine front was seen as nothing more than a sideshow to draw away the largest possible number of British troops from the European fronts. Thanks to the pipe dream of renewing another Suez Canal assault, the VIII Army Corps remained in the theater and carried out small raids, which maintained high levels of British angst. After the success of a much smaller raid against an outpost at Katya (Katia) on April 23, 1916, the commanding officer Kress von Kressenstein decided to launch a major assault against the British positions around Romani in order to push the enemy back to its original position on the canal. Unfortunately for the Ottomans, the Katya raid alerted the British command which in turn strengthened its positions. Thus, the British easily dealt with the two-day-long Ottoman assault (August 4 and 5) but did not follow up their victory efficaciously.

The British command paid little attention to Ottoman tactical weakness and instead focused on constructing a railway, water pipeline, and other supply facilities that could support a large campaign. The Fourth Army Commander, Cemal Pasha, and von Kress evacuated all of the indefensible forward positions and began to entrench a defensive line between Gazze (Gaza) and Birüs-Sebi (Beersheba). The Ottoman entrenchments and defense works had little depth but were of modern design. However, due to the shortage of barbed wire and entrenchment tools, priority was given to the Gaza fortifications, whereas the large expanse between Gaza and Beersheba was superficially prepared. In March 1917, General Archibald Murray, commander in chief of Egyptian Expeditionary Forces (EEF), at last satisfied with the level of logistics preparation and force buildup, launched his long-awaited offensive targeting Gaza on March 26. Initially, surprise was complete as the Ottoman side, which had grown weary of waiting, saw its forward defense troops easily taken prisoner by British cavalry. But poorly coordinated piecemeal, slow British assaults died down in front of secondary Ottoman positions. An equally uncoordinated Ottoman counterattack the next day failed, but Ottoman flanking movements in the desert forced the British troops to withdraw in safety.

Von Kress improved the fortified positions around Gaza and tried in vain to strengthen his defense line linking Beersheba. Undeterred by his old plan’s failure, Murray launched a similar assault (once again paying limited attention to the weak Ottoman defenses between Gaza and Beersheba) on April 14. This time he made use of heavy artillery fires, naval gunfire, aerial bombardment and, for the first time in the Middle East, poisonous gases (against the deep reservations of most of his officers), and even a small tank unit. The Ottoman troops had absolutely no protection against gases but, due to weather conditions or poor delivery, the gas shells (around 2,500 chlorine shells) did no harm to the defenders. Similarly, small numbers of tanks did not alter the situation and fell prey to deadly Ottoman artillery fire. In short, the staunch Ottoman area defense effectively stopped the British assault waves and inflicted heavy casualties.

The disastrous end of the Second Battle of Gaza disappointed the British High Command, and General Murray and other high-ranking officers were replaced immediately. The new commander, General Edmund Allenby, was a notable cavalry officer but was also known to be cautious. So another half a year was spent waiting for the arrival of reinforcements and improving lines of communication and logistics. While the British expeditionary forces in Palestine were undergoing a major transformation and expansion, the Ottoman General Staff turned its attention to another front; Iraq and its imminent collapse.