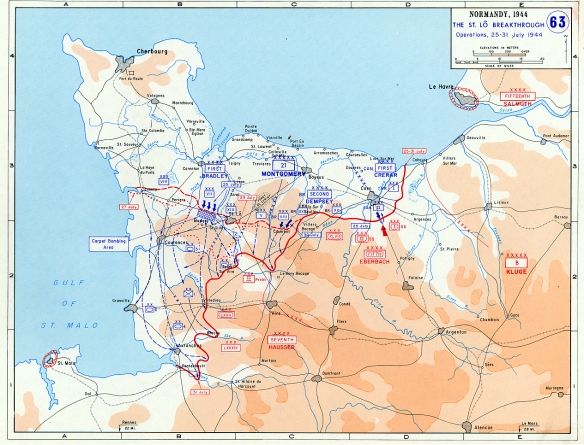

Corlett would require ten days of hard fighting to take Vire, but the tough battle waged by his XIX Corps freed VII and VIII Corps to exploit the breakthrough. Moving west of the Vire River and then heading south toward Vire, XIX Corps ran into two panzer divisions which Kluge had rushed into the breach as the nucleus of a counterattack force. For the next four days, the two sides battled around the small crossroads town of Tessy-sur-Vire, which finally fell to Combat Command A of the 2d Armored on 1 August. Although the XIX Corps had not yet reached Vire, it had blocked German efforts to reestablish a defensive line. Freed from concern for its flank, the VII Corps continued its drive south, while the 4th and 6th Armored Divisions of VIII Corps rolled down the coastal road into Coutances on 28 July and then to the picturesque, seaside city of Avranches on 30 July. The capture of Avranches opened the way for an advance west to the critical Breton ports.

As July turned to August, changes in the American command structure brought a dynamic new figure to the stage. Overbearing, often profane, yet also sensitive and deeply religious, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., had already earned a reputation as an outstanding field general, as well as a frequently difficult subordinate, in North Africa and Sicily. Few, if any, commanders in World War II could match his talent for mobile warfare, his ability to grasp an opportunity in a rapidly changing situation, and his relentless, ruthless drive in the pursuit. The buildup and expansion of the Allied lodgment had now reached the point where Bradley could bring the Third Army headquarters and its flamboyant leader into the field. He himself assumed command of the new 12th Army Group, and Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges, a modest and competent professional, took his place at First Army. Third Army would command VIII Corps and the new XV, XX, and XII Corps, while First Army retained control of the V, XIX, and VII Corps. Although introduction of an American army group was supposed to be followed by the assumption of overall command in the field by the Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower deferred this step until he could physically establish his headquarters on the Continent. In the meantime, he allowed Montgomery to coordinate both army groups in the field.

Turning the corner at Avranches, Patton’s Third Army raced west into Brittany. Hitler had ordered his troops to hold the ports “to the last man,” tying down American units and keeping the ports out of Allied hands as long as possible. However, German disarray enabled the Allies to send only VIII Corps into Brittany, rather than the entire Third Army as earlier planned. At Patton’s direction, Middleton flung the 4th Armored Division toward Quiberon Bay to cut off the peninsula at its base, while the 6th Armored Division drove from Avranches west toward Brest at the extreme tip of Brittany, bypassing strongpoints along the coast in an effort to seize the port before the Germans could react. Eager to finish its work and join the main drive farther east, the 4th Armored seized Rennes and encircled Lorient, on the southern coast of Brittany. The 6th Armored covered the 200 miles to Brest in five days, but the tankers found the city’s defenses too strong to take by a quick thrust. Not until 18 September did VIII Corps units finally batter their way into Brest and force the garrison’s surrender. To the east, it took a rugged, house-by-house fight by the 83d Infantry Division to occupy the ancient Breton port of St. Malo. By the time the Breton harbors came under Allied control, demolitions had rendered them useless, but events to the east had already reduced them to minor importance.

The Allies had moved quickly to take advantage of the dangling German flank east of Avranches. By 3 August, Montgomery and Bradley had decided to send just one corps into Brittany and turn the rest of 12th Army Group east in an effort to destroy the German Seventh Army west of the Seine. Under Patton’s Third Army, Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip’s XV Corps, which had been acting as a shield for the VIII Corps’ move into Brittany, drove east to Mayenne, Fougeres, and Laval, scattering the few German units in its path. To the north, Hodges’ First Army ran into tougher opposition, particularly on the V Corps and XIX Corps fronts, where Gerow and Corlett were encountering stubborn resistance in their advance toward Vire. Collins’ VII Corps enjoyed easier going on First Army’s right, capturing the key road center of Mortain and racing south to link up with the XV Corps at Mayenne. American troops were moving rapidly, but Bradley viewed with great unease the narrow Mortain-Avranches corridor which connected his far-flung units.

Bradley’s unease was well founded. Faced with a choice between attempting to reconstruct a defensive line in Normandy and withdrawing, Hitler opted for the former alternative. On 2 August, he directed Kluge to counterattack from the Vire area west to the sea, cutting off Third Army and restoring the German front. As so often happened in the Normandy Campaign, German efforts to prepare the blow were marked by a lack of coordination and communication, a problem only enhanced by the mutual distrust between Hitler and his generals following the July coup attempt. Confronted with a desperate situation, Kluge lacked the time to prepare the massive stroke that Hitler had in mind, and his buildup was hurried and disjointed. By the time the Germans launched their attack in the early morning darkness of 7 August, Kluge had been able to assemble only three panzer divisions with a fourth panzer division ready for exploitation, a far cry from the full panzer army that Hitler had envisioned.

Nevertheless, the attack gave the Americans plenty of trouble. Achieving surprise, the Germans drove as much as six miles into the American front, particularly in the Mortain area where the 2d SS Panzer Division overran positions that had only just been occupied by the 30th Infantry Division. By daylight, however, the German thrust was already faltering. Disorganized in the attack, the 2d SS Panzer Division in the center had been able to employ only a single column in the early stages, and the 116th Panzer Division in the north had not attacked at all. On the 2d SS Panzer Division’s front, a battalion of the 30th Division dominated the battle area from Hill 317 just outside Mortain, beating off every attack sent against it. Supplied by air drops, the unit held for four days until its relief, calling down artillery fire on German formations in the surrounding area and earning for its division the title “Rock of Mortain.” Meanwhile, as Allied aircraft pummeled the Germans, Bradley, Hodges, and Collins sent the 4th Infantry Division into the northern flank of the penetration while the 2d Armored and 35th Infantry Divisions struck from the south. By late afternoon, Kluge was convinced that the offensive had failed, but at Hitler’s direction he continued to press the attack.

Hitler’s obstinacy created a golden opportunity for the Allies. Assured by Hodges that First Army could hold at Mortain, Bradley presented Montgomery with a proposal on 8 August. From the eastern end of the crescent, which represented the Allied front, First Canadian Army had started an offensive toward Falaise, and Bradley now proposed that Patton’s Third Army, on the extreme southwest, drive across the German rear to link up with the Canadians and trap the Germans in a gigantic pocket. While Montgomery had set his eye on an even deeper envelopment to the Seine, he accepted Bradley’s plan and issued orders providing for a linkup between the Canadians and the Americans just south of the town of Argentan. From Le Mans, which it had reached on 8 August, Haislip’s XV Corps drove toward Argentan. A 25-mile gap lay between Haislip’s forces and VII Corps’ flank at Mayenne, but the Germans were too widely dispersed to take advantage of XV Corps’ exposed position. On 12 August, XV Corps troops seized Alencon, about twenty-five miles south of Argentan, and Patton authorized a drive north toward Argentan and Falaise to meet the Canadians, who, slowed by fierce opposition and command inexperience, were still far north of Falaise.

At this point, Bradley halted Third Army short of Argentan, despite Patton’s vigorous protests and jovial offers to “drive the British into the sea for another Dunkirk.” The order remains the subject of considerable controversy, with many arguing that Bradley should have crossed the army group boundary line and completed the encirclement. Bradley himself later criticized Montgomery for failing to act more vigorously to close the gap, although he had never recommended to Montgomery an adjustment of the army group boundary to permit the Americans to advance farther north. The American commander later recalled his concern about the potential for misunderstanding as Canadian and American units approached one another, but he also admitted that the army groups could have designated a landmark or tried to form a strong double shoulder to minimize accidents. A more probable consideration in Bradley’s decision was his anxiety, possibly based on secret ULTRA intercepts, that American forces were becoming overextended and vulnerable to an attack by the German divisions believed to be fleeing through the gap. In his memoirs, Bradley stated he was willing to settle for a “solid shoulder” at Argentan in place of a “broken neck” at Falaise.

Actually, as of 13 August, few German units had left the pocket. Kluge wanted to form a protective line on each salient shoulder to cover the withdrawal of his forces to the Seine, but Hitler, still planning a drive to the sea, refused to approve it. On 11 August, the Fuehrer had authorized a withdrawal from the Mortain area to counter the growing threat to Seventh Army’s rear, but only as a temporary measure prior to a renewal of the offensive to the west. The troops in the pocket, however, were unable to mount a major, coordinated blow in any direction. Lacking resources, especially fuel and ammunition, and under pressure from the repeated Allied blows, they could do little more than fight a series of delaying actions around the fringes of their perimeter. On 15 August, Kluge’s staff car was strafed by Allied planes, and the field marshal was left stranded for twenty-four hours, arousing Hitler’s suspicions that he was trying to broker a deal with the Allies. When Kluge finally reappeared, he recommended an immediate withdrawal from the pocket. A sullen Hitler agreed but replaced Kluge with Field Marshal Walther Model, whose loyalties were beyond question. During his return to Germany, the despondent Kluge committed suicide.

Behind him, Kluge left a Seventh Army that, for all practical purposes, had ceased to exist as a fighting force. Under constant pounding from Allied air and artillery, lacking ammunition and supplies, and exhausted from endless marches on clogged roads, some German units panicked or mutinied, but others managed to maintain discipline and fought grimly to keep escape routes open through the narrowing gap. Observing the area after the battle, an American officer saw “a picture of destruction so great that it cannot be described. It was as if an avenging angel had swept the area bent on destroying all things German . . . As far as my eye could reach (about 200 yards) on every line of sight, there were . . . vehicles, wagons, tanks, guns, prime movers, sedans, rolling kitchens, etc., in various stages of destruction.” Despite Allied efforts, a surprising number of German troops had escaped by the time the Americans, Canadians, and Polish armor serving with the Canadians finally sealed the pocket on 19 August. They had left behind, though, most of their artillery, tanks, and heavy equipment as well as 50,000 comrades. German . . . As far as my eye could reach (about 200 yards) on every line of sight, there were . . . vehicles, wagons, tanks, guns, prime movers, sedans, rolling kitchens, etc., in various stages of destruction.” Despite Allied efforts, a surprising number of German troops had escaped by the time the Americans, Canadians, and Polish armor serving with the Canadians finally sealed the pocket on 19 August. They had left behind, though, most of their artillery, tanks, and heavy equipment as well as 50,000 comrades.