Hernán Cortés returned to Tenochtitlán with an enlarged force of conquistadores and much more important, large numbers of allied Mesoamerican warriors who came to complete what the Spanish had started but could not finish on their own. Cortés first systematically dismantled the supports of the Aztec Empire, forging alliances with vassal city-states around the interconnected lakes of the Central Valley. Tepeca and Cholula joined the Spanish alliance. Then, in a key event, Tetzcoco—on the eastern side of Lake Texcoco—long an ally of Tenochtitlán, switched sides. This gave the attackers the critical forward base they needed. Some Tetzcoco nobles sensed the end was near for Aztec hegemony; others hoped to replace their own king in the wake of the chaos to come. In short, as the brutal authoritarianism of the Aztecs collapsed, older traditions of fierce internal political rivalry among the noble classes and of independence of the city-states of the Central Valley reemerged. The Spanish were there largely to collect the pieces of the coming political, social, and demographic chaos.

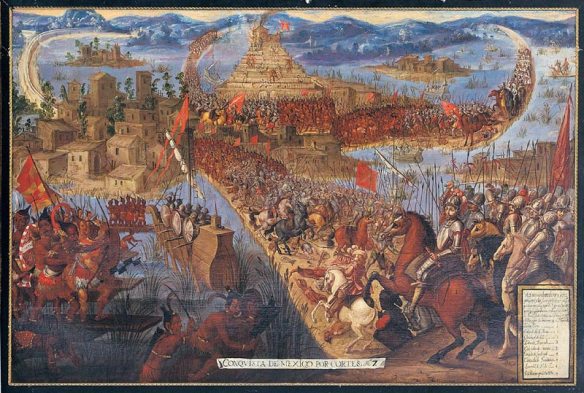

The Aztecs enjoyed a major strategic advantage: they could attack at any point along the lakeshore with a vast fleet of war canoes. It was critical, therefore, that Cortés had 14 brigantines built in Tetzcoco using timber and struts hauled from the wrecks beached at Vera Cruz. They were pulled over the mountains by hundreds of Mesoamerican porters. The high-decked brigantines were launched on April 28, 1521, again vitally accompanied by thousands of Tlaxcalan and other allied braves in war canoes. The brigantines were unassailable by the Aztecs who could neither reach their high decks and castles from flat-bottomed canoes nor withstand withering fire spat at them from swivel guns and decks lined by arquebusiers and crossbowmen. They also were overwhelmed at water level by thousands of Indian enemies fighting canoe to canoe. The Aztec canoe fleet was destroyed, denying Tenochtitlán any means of resupply of food or fresh water. Meanwhile, 1,000 conquistadores and many tens of thousands of Tlaxcalan and other Mesoamericans warriors (over 95 percent of the attacking force) cut the causeways, isolating the island city.

The Spanish set up heavy cannon and some falconetes and settled in for a 93-day siege. But this was a siege with a difference: during the day, Spanish and Tlaxcalans fought down the causeways toward the city, slaughtering as many Aztec warriors as they could before withdrawing for the night. Each sortie consumed a bit more of the causeway and then the city itself, progressively opening lines of fire for the artillery and firearms troops and charging lanes for lancers. The fighting was close: Cortés was unhorsed three times and once nearly dragged off to be ritually sacrificed. Some Spanish penetrated too far in a June attack and were ambushed and taken. Fifty conquistadores were carried off along with hundreds of Tlaxcalans. All were sacrificed in view of their comrades, their hearts cut out while still beating by high priests wearing cloaks of flayed human flesh. The bodies were tossed down the blood-slicked steps of the Aztec temples, or roasted, with their skins sent at night to shoreside towns to show that the Spanish were mortal, and to promise Aztec revenge on any who aided them. The Spanish gave no quarter either: they slaughtered hundreds each day and tore down whole blocks of houses and temples, all to no greater end than a conquest that would make them rich beyond the avarice of the basest among them.

Without a hint of moral awareness, let alone remorse, Cortés wrote to Emperor Charles V: ‘‘the people of the city had to walk upon their dead. . . . So great was their suffering that it was beyond our understanding how they could endure it. Countless numbers of men, women and children came toward us, and in their eagerness to escape many were pushed into the water where they drowned amid the multitude of corpses.’’ The Tlaxcalans took a full measure of revenge on the Aztecs, including thousands of women and children whom they slaughtered along with blood-stained priests and warriors. That caused humbug moralizing among the Spanish. On August 13, 1521, the third and last Aztec leader to face the Spanish, the boy-emperor Cuauhtémoc, surrendered Tenochtitlán. Cortés later had him murdered during an expedition to conquer Honduras in 1524.

Suggested Reading: Hugh Thomas, Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés, and the Fall of Old Mexico (1994); Ross Hassig, Aztec Warfare (1988); Richard Townsend, The Aztecs (1990; 2000).