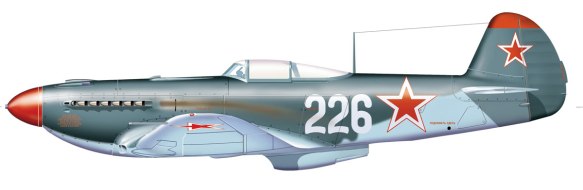

Yak-9U

BEA Vickers Viking 1B

It began slowly, with what would later come to be condescendingly called “the Little Lift.” In April and May 1948, thirty U. S. Air Force C-47s, some still bearing black-and-white D-Day stripes, plus two British Royal Air Force Dakotas and a little Avro Anson hauled food and supplies for the Allied garrisons-soldiers, staffers and diplomats. Nobody dreamed we’d be supplying the city itself; the Little Lift was simply a stopgap to relieve the temporarily trapped Yanks and Brits.

It was during the Little Lift that an unfortunate but precedential incident occurred: A British Vickers VC.1 Viking transport was about to land at Gatow, the main airport in the British Zone, when a Yak 9 single-seat fighter suddenly swooped beneath the Viking and pulled up sharply shearing off the larger planes right wing.

The Russian pilot, who had been practicing aerobatics nearby, probably intended to do a roll around the British airliner but misjudged his pull-up. The rash “Watch this!” maneuver killed the Russian, as well as two British crewmen and 12 passengers aboard the Viking, including two Americans.

What made the crash precedential was the decisive U. S. reaction: General Clay ordered fighter escorts for future missions. The Russians ordered the cessation of night flying and specified various traffic reroutings and what might be termed “new rules,” all of which the Americans pointedly ignored. But never again would they seriously challenge the airlift. Why?

The Soviets were often outstanding pilots, and some had amassed enormous kill totals, but by wars end they were invariably notched against ponderous Luftwaffe bombers and Stukas on the Eastern Front, often flown by last gasp German neophytes. How the Soviets would have fared against equally battle-hardened USAF dogfighters in superior late-model Mustangs presumably gave them pause. Furthermore, Soviet pilots followed visual flight rules and had no idea how to fly on instruments, so in lousy weather, airlift pilots could count on cloudy but Russian-free skies.

Nor did it hurt that a fighter group of Lockheed P-80 straight-wing jets was put on standby in the United States. Sixty Boeing B-29s had already arrived in England, and some were reportedly flying patrols high above the airlift corridors. The Soviets may have assumed the Superfortresses were equipped with nukes, though in fact they weren’t.

During the summer of 1948, the British operated some of the most impressive, albeit unusual, aircraft in the airlift; six huge Short Sunderland flying boats that landed on the Havelsee, a large Berlin lake. The Sunderlands flew in 5,000 tons of precious salt, which would quickly have eaten away at aluminum landplanes but didn’t affect the corrosion-proof flying boats.

The Sunderlands, so noticeable and spectacular, did as much for Berliners’ morale as they did for their food-preparation and preservation capabilities. Everybody loved the big four-engined Shorts, which looked something like pigs with wings. One Sunderland pilot en route to the Havelsee recalls watching a Russian biplane doing aerobatics in front of him, and when the Russian pilot suddenly noticed that approaching monstrosity, he was evidently so shocked that he cross-controlled his airplane and spun-much to the amusement of the Sunderland’s crew.

When the weather allowed, opposing pilots played games in the air corridors. The Soviets specialized in buzz jobs, aerobatics, towing targets amid the Allies’ transports, bombing practice and even broadcasting false nav beacons to lure pilots off course. The Americans responded by flying C-54s at treetop level down the Unter den Linden, the broad central avenue through the Soviet Zone. Late at night, U. S. pilots would glide their Douglases quietly down over the Soviet barracks, then open all four throttles to max power, shattering windows, rattling chimneys and rudely awakening the groggy Russians.