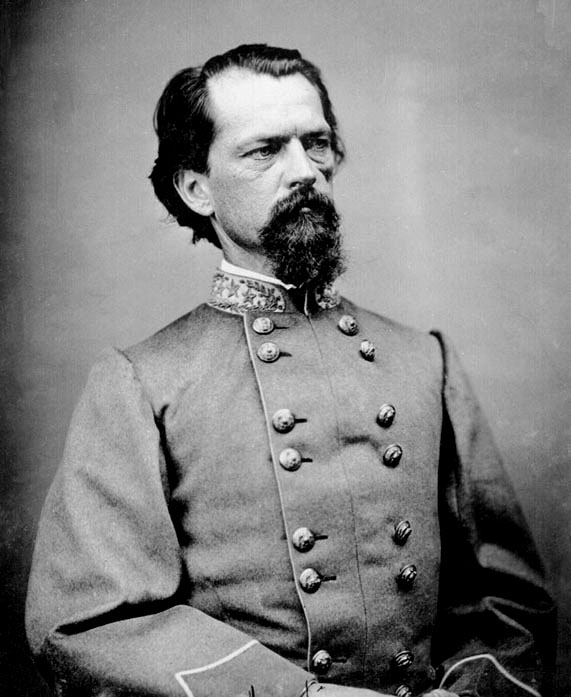

John B. Gordon, commander of the Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, launched the last offensive of that famous fighting force at Fort Stedman, on March 25, 1865.

The Confederates scored initial success in the Fort Stedman attack, top, breaking through the Union line and capturing the stronghold. Their failure to capture all of Stedman’s supporting earthworks, however, allowed the Federals to launch a counterattack that put the Southerners to flight, bottom.

Gordon’s initial result was a resounding success. Stedman and Batteries 10 and 11 were captured in the initial rush. Battery 12 to the south fell soon thereafter. But things also began to fall apart very quickly. Battery 9 made a determined stand, and Fort Haskell to the south proved unassailable. These locations would be the “shoulders” of Gordon’s breach, about 1,000 yards long at its widest that morning. In addition, Gordon’s plan had a serious flaw. There were no set of three forts immediately behind Stedman. The three hundred picked sharpshooters milled about in the darkness trying to find these nonexistent earthworks, wasting valuable time. Lastly, Gordon did not account for Hartranft’s Division,with over 4,000 men in the area, or the two forts on the old Confederate Dimmock Line.

Union Brigade commander McLaughlen, driven from Stedman in the pre-dawn darkness, organized an early small counterattack. Though he was captured, this fight temporarily discomfited the Rebel attackers and gave Hartranft and others time to organize larger assaults. Ninth Corps artillery from Fort Haskell, Battery 9, and other works pummeled the Confederates as the sun began to rise. It soon became clear to Lee and Gordon that the assault had failed, even before Hartranft’s massive counterattack.

General Gordon’s last action of the war occurred on March 25, 1865, when he launched a skillful night attack that temporarily captured Fort Stedman, Virginia. Fresh Union troops then forced him back, and he accompanied Lee’s retreat out of the Richmond area.

For nine months, Petersburg was under siege by the Army of the Potomac and the overall Union commander, General Ulysses S. Grant. The two great armies had fought a bloody campaign in the spring of 1864, and then settled into trenches that eventually stretched for 50 miles around Petersburg and the Confederate capital of Richmond. Lee could not win this war of attrition, but his men held out through the winter of 1864 to 1865. Now, Lee realized the growing Yankee army could overwhelm his diminishing force when the spring brought better weather for an assault. He ordered General John B. Gordon to find a weak point in the Federal defenses and attack.

Gordon selected Fort Stedman, an earthen redoubt with a moat and 9-foot walls. Although imposing, Gordon believed it offered the greatest chance for success since it was located just 150 yards from the Confederate lines–the narrowest gap along the entire front. Early in the morning of March 25, some 11,000 Rebels hurled themselves at the Union lines. They overwhelmed the surprised Yankees at Fort Stedman and captured 1,000 yards of trenches. After daylight, however, the Confederate momentum waned. Gordon’s men took up defensive positions, and Union reinforcements arrived to turn the tide. The Rebels were unable to hold the captured ground, and were driven back to their original position.

The Union lost around 1,000 men killed, wounded, and captured, while Lee lost probably three times that number, including some 1,500 captured during the retreat. Already outnumbered, these loses were more than Lee’s army could bear. Lee wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that it would be impossible to maintain the Petersburg line much longer. On March 29, Grant began his offensive, and Petersburg fell on April 3. Two weeks after the Battle of Fort Stedman, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.