Under Janos Hunyadi the Hungarians began to use warwagons, not surprising given the large numbers of ex-Hussites employed as mercenaries. These wagons appear to have differed little from their original Hussite counterparts and fulfilled a very similar role.

The wagon fortress or wagon camp was a defensive arrangement of war carts chained together, wheel to wheel, and protected by heavy wooden shielding. Manned with bowmen and hand-gunners, these late medieval “armored vehicles” protected against cavalry assault. First used in the Bohemian civil war after 1419 by the Hussites (followers of the reforming theologian Jan Hus, 1369?-1415), the wagon fortress tactic was introduced to the Ottomans by the Hungarians during the 1443-44 Balkan campaign of the Hungarian national hero Janos Hunyadi (1407?-1456). Hunyadi, then governor of Transylvania (then a frontier province in eastern Hungary, now in Romania), employed some 600 wagons, operated by Czech mercenaries, against the Ottoman Turks. By the end of the conflict, the Ottomans knew how to besiege the tabur, that is, the Christian wagon camp, so called in Ottoman sources after the Hungarian usage, szekér tabor, or wagon camp. In the Battle of Varna (November 10, 1444), the Ottomans defeated the crusaders’ army and captured the Christian war wagons and weapons. While the speed with which the Ottomans adapted their way of fighting to the tactic of their Christian adversaries is remarkable, it should not surprise us, for the wagenburg tactic was not dissimilar from the Turks’ own fighting traditions. Moreover, the Turks of western Anatolia also used fortified camps in the 14th century. In 1313, for instance, a Turkish raiding party, using the carts that transported the booty, erected such a fortified camp against the Byzantines who had intercepted them.

The Bohemian Hussites in the 1420s and 1430s for example, used cannon and primitive ‘hand culverins’ (ancestors of the arquebus) to help defend the mobile fortresses which they constructed on the battlefield by chaining together lines of war-wagons. One key difference, however, was introduced by the new weapons: now the side best provided with artillery could often compel its enemy to make an attack (or suffer interminable bombardment), and so secure for itself the advantages of the tactical defensive.

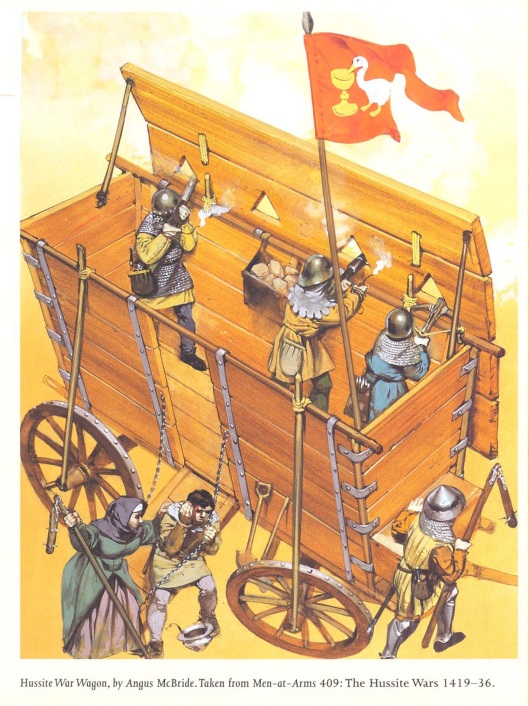

Greater mobility, at least for the march, was achieved by the Hussites, who mounted their cannon on carts. For battle, however, these guns were dug-in, being incorporated into the Hussites’ distinctive wagon-forts (Wagenburgs), which were mobile field fortifications formed out of wagons and manned by handgunners, crossbowmen, and men wielding chain flails. The Hussites were admittedly something of a military anomaly, but by the mid-fifteenth century cannon and handguns were beginning to make their mark on battlefields across Europe.

The earliest hand culverins were a kind of mini-cannon with a touch hole, attached to a pike staff and propped in a rest for firing. John Zizka, the Bohemian leader of the Hussite Wars, made good use of handgunners armed with culverins in his Wagetburgen, the laager of wagons that constituted a kind of mobile fortress. His handgunners stood in the wagons, whose sides made an excellent rest for their weapons. The wagons could also be mounted with light cannon; while pikemen and halberdiers sheltered behind the carts, ready to make their charge when the advancing enemy had been halted and disordered by gunfire and archery. Zizka’s Wagetburgen proved formidably successful against the German armies sent to fight him. Unlike the Hungarians, or the Russians in their wars against the Tatars, the Germans learned little from this experience.