Wooden trestles were easily destroyed, so blockhouses were built to protect bridges and vulnerable stretches of track. All were loopholed for musketry, and some had stockades, and embrasures for light field pieces.

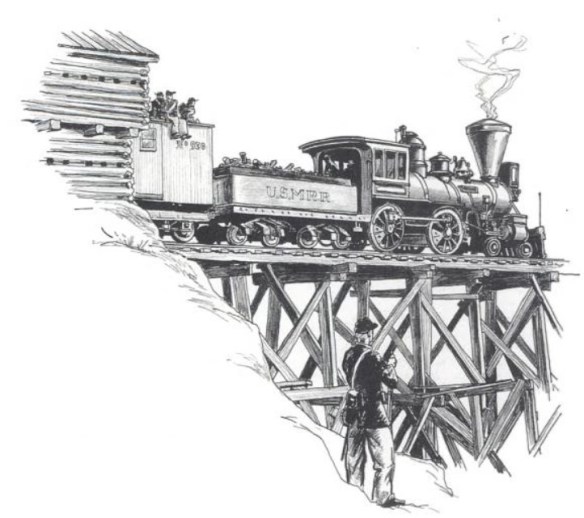

Prefabricated portable truss built by engineers for U.S.M.R.R.

In the Civil War, for the first time in history, railroads played a major role in warfare. Campaign strategy was often based on the availability and capacity of a railway line, and the construction, maintenance, and defense of these vital links involved large numbers of men and much equipment. Throughout the war the railroads bore an ever-increasing load, carrying tens of thousands of men and hundreds of thousands of tons of urgently-needed supplies.

Sherman said in his memoirs that the Atlanta campaign would have been an impossibility but for the single track road, much of its 473 miles subject to sudden raids, which carried supplies for 100,000 men and 35,000 animals for 196 days. For that matter the whole series of battles around Atlanta centered around the railroads, and the bloody fighting around Petersburg in 1865 was in great part dictated by the Federal threats to the railroads linking Richmond with the South, and Lee’s desperate attempts to keep that line of communications intact.

As far back as 1837, the United States government had adopted the policy of loaning technically-trained officers to the growing railroad industry, both sides profiting by the experience. By coincidence, both Cameron and Scott of the War Department were ex-railroaders, and McClellan himself had been a railroad executive. There was at all times during the war an awareness by the Federal authorities of the necessity of keeping the railroads in a state of high efficiency, and a determination to see it done at all costs.

Of the 30,000-odd miles of railroad in operation in the United States at the outbreak of the war, less than 9000 miles lay in the seceding states. This system or systems, for they were not all connected, had been dependent, to a great extent, on the North for locomotives, rolling stock, and railroad iron. Once this supply was cut off, the Southern railroads began to deteriorate, a process hastened by the inroads of the Federal armies. As early as January 1862 the Confederate Quartermaster General complained that some of the railroads on which the government was depending for transportation were only operating two trains a day, and those at an average six miles per hour!

A Confederate staff officer wrote of a troop movement:

“Never before were so many troops moved over such worn-out railways, none first-class from the beginning. Never before were such crazy cars—passenger, baggage, mail, coal, box, platform, all and every sort wobbling on the jumping strap-iron—used for hauling good soldiers.” (from Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer, by General G. Moxley Sorrel)

Certainly the South had the advantage of interior lines of communication, but when the lines were only “two streaks of rust and a right of way,” much of that advantage was lost. However, bad as the Southern railways were, they played an important part in the maneuvers by which the Confederates switched their outnumbered troops from one theater to another. By such a movement, Longstreet rushed a whole corps of 18,000 from the Army of Virginia to Georgia, by various routes and railroads, in time for the decisive second day’s fight at Chickamauga.

In the war’s early days, the Northern railroad companies met with the government and agreed on fixed rates for hauling supplies and troops. This was adhered to throughout the war, although other prices soared. It was cheaper, the government found, to transport 1000 men a distance of 100 miles for the price of $2000.00 than to march them the same distance by road. When space was at a premium, as in Pope’s campaign in Virginia in ’62, priorities were awarded in the following order: Rations, forage, ammunition, hospital stores, veteran infantry regiments, and, lastly, “green” regiments. Batteries marched, except in emergencies, and cavalry marched and wagons were driven.

There were very few actual military railroads during the war, but both sides occasionally took over privately-owned lines and ran them when the situation demanded.

The work of maintenance of the United States Military Railroads fell on the Construction Corps. This corps, which at its peak numbered over 24,000 men, performed prodigies, building trestles, repairing bridges, and laying track, often under fire from guerrillas and enemy scouting patrols. They were civilians and were well paid—$2.00 a day and double for overtime. While the mileage of the United States Military Railroads did not run much above 2000 miles, there were over 6000 cars in operation and more than 400 locomotives.

The bridge-building feats of the Construction Corps were fantastic. Operating in many cases with unskilled labor, they could build a one hundred and fifty-foot span with a thirty-foot elevation across a creek in fifteen hours. Some of them looked flimsy enough, but they held. Speaking of Herman Haupt, the engineering genius who headed the railway and transportation service, Lincoln said:

“That man, Haupt, has built a bridge across Potomac Creek, about four hundred feet long and nearly a hundred feet high, over which loaded trains are running every hour, and, upon my word…. There is nothing in it but bean-poles and corn-stalks.”

The Chattahoochie bridge, eight hundred feet long and nearly one hundred feet high, was rebuilt, starting with unfelled timber, in four and a half days. Trusses were designed with interchangeable parts, adapted to any span. Timber was plentiful in most of the war theaters and was usually available at the building sites, where it was cut and trimmed on the spot. Where necessary, prefabricated trusses were brought in on flatcars. Toward the close of the war, the Union engineers were rebuilding bridges and repairing tracks almost as fast as the Confederates could destroy them.

When Hood cut Sherman’s rail communications at Big Shanty and Resaca, he destroyed over thirty-five miles of track as well as burning bridges. Although a number of construction men had been killed, repair work began before Hood had left the railroad. One twenty-five mile stretch was laid in seven and a half days. New ties had to be cut, and the rails brought forward almost two hundred miles.

The Federal cavalry raiders found that the Southerners, too, could repair track at a great rate, even when the business of railroad destruction had become almost a science. Although one lone saboteur and a loosened rail could add up to a lot of trouble, the following method was used when time permitted a thorough job to be done.

The men were divided into parties, and the men of the first party distributed along the track, one man to each tie. At a signal the whole section of track was raised on edge and tipped over, ties on top. The ties were pried loose from the rails and the first party moved on to another section, while the second party stacked the ties and laid the rails over them. The ties were then set alight and when the rails were red-hot the third party, using pinchers or “railroad hooks,” bent them around trees and also twisted them. The twist was important, for both the Southern and Northern repair crews became as adept at straightening rails as the soldiers were at bending them. Rails which were not bent in too small a U could be straightened, but a scientifically twisted one had to go back to the rolling mill.

No tracks laid down in as great a hurry as these military railroads and subject to the above treatment were any joy to ride on. Contemporary photographs reveal stretches of track which any self-respecting railroader would hesitate to travel in a handcar. But they did the job, and that was all that mattered.

The wrecking of a railroad might delay a whole campaign or turn a victory into defeat. The wild ride of the “General” under Andrews and his desperate crew had its inception in Gen. O. M. Mitchell’s campaign for Chattanooga, and its purpose was to isolate that city by destroying bridges on the Georgia State railroad and one on the East Tennessee. The attempt failed and Mitchell abandoned his drive on the city.

By the war’s end most of the railroads in the South had been destroyed by the invading Federals or crippled by continued use without repair. The only Northern road to suffer much damage was the Baltimore and Ohio, some of whose tracks ran through the battleground of northern Virginia.

Besides transporting men and supplies to the theaters of war, these railroads also brought back many whose fighting days were over, at least for the time. Trainloads of wounded were carried back from the fronts, at first in any makeshift car or coach and later in specially-designed hospital trains. These were marked by bright red stacks, and at night by three red lanterns hung in a row beneath the head lamp.

Early in the war cars had been armed and even armored. An armored (bulletproof) car patrolled the Philadelphia and Baltimore Central, and a Confederate field gun on a flatcar shelled the enemy at the Battle of Seven Pines. A heavily-armored siege gun was used by Grant during the fighting around Petersburg, as was a 13-inch mortar, complete with ammunition cars and locomotive.

To combat repeated raids on stations and bridges, Major General Dodge, foremost railroad builder of the Western armies, developed a system of blockhouses and stockades. These little forts worked well against attacks by cavalry alone, but when accompanied by horse artillery, the raiders usually had it all their own way. No method of assuring one hundred per cent protection for the miles of railroad was ever found. The only answer was to keep the repair crews well supplied and in constant readiness.

Loading and unloading, and the prompt return of empty cars, became at times a major problem. Quartermasters in the field were prone to use rolling stock as portable warehouses and considerable effort was, at times, required to keep the empties moving. Train schedules were almost impossible to keep and the telegraph was usually tied up by the military. There was also much interference by subordinates, in the Quartermaster’s Department and officers in the field. In the Federal service this resulted in positive orders from the Chief of Staff forbidding all orders, except through the chief of the Construction Corps.

Despite these difficulties, which were increased by the fact that many of the lines were single-tracked and that there was no uniformity of rail gauge throughout the nation’s railroads, the railroaders, Union and Confederate, lived up to the tradition of their calling, and, where humanly possible, “kept ’em rolling.”