Chaotic and inconclusive war between the United States and Great Britain that nevertheless provided a new surge of American nationalism. There were four main causes: American insistence upon its neutral trade with both sides in the Napoleonic Wars, British boarding of American ships on the high seas and impressment of American seamen, conflicts between American pioneers and British-supported American Indians on the western frontier, and the desire for land in Canada. William Henry Harrison’s victory at Tippecanoe in 1811 was used as propaganda by the bombastic “War Hawk” political faction to demand action against Britain for supposedly arming the Indians and as an excuse for the seizure of Canadian land.

Soon after the U. S. Congress boldly declared war on Great Britain on 18 June 1812, Secretary of War William Eustis and his generals decided that the best defense was a good offense and set their sights on Canada. Major General Henry Dearborn envisioned a four-pronged attack: from Lake Champlain to Montreal; from Sackets Harbor, New York, to Kingston, Ontario; west across the Niagara River; and east across the Detroit River.

The British were too involved with Napoleon in Europe to commit significant naval, military, or matériel resources to North America in 1812 or else Britain might have crushed the United States early. The small American navy was a match for British ships in single combat, but the initial unpreparedness and inadequacy of American land forces spelled disaster for Dearborn’s plan. The chain of command was unclear, with junior officers of regulars often expecting to take command over senior officers of militia.

On 17 July 1812, American lieutenant Porter Hanks, who had not heard that there was a war on, surrendered the 57- man garrison of Fort Mackinac to British captain Charles Roberts’s 900 soldiers. This surrender gave Britain control of Lake Huron. Pro-British Potawatamis massacred about 70 American soldiers and civilians under Captain Nathan Heald as he was surrendering Fort Dearborn, now Chicago, on 15 August. Brigadier General William Hull first intended to attack Fort Malden, Ontario, but dropped that plan and instead surrendered Fort Detroit without a fight on 16 August to Major General Sir Isaac Brock. Hull was court-martialed, convicted of cowardice and neglect of duty, and condemned to be shot, but President James Madison commuted the sentence in light of Hull’s service in the Revolutionary War.

Stephen Van Rensselaer, a major general of New York militia despite his utter lack of military experience, crossed the Niagara River with about 4,000 of his 6,000 men to invade Ontario at Queenston Heights on 13 October. Although the British garrison was only about 300 strong, they held Van Rensselaer’s disorganized force on the heights. Brock was killed as his 1,800 reinforcements routed the Americans. Dearborn’s campaign against Montreal fizzled in November when his 8,000 troops, marching north from Albany, refused, like the New York militia across from Queenston Heights, to cross the Canadian border.

In the Northwest theater, Captain Zachary Taylor successfully defended Fort Harrison, Indiana, against eight-to-one odds on 4 September. Colonel Henry Procter’s 500 British and 600 Wyandots crushed Brigadier General James Winchester’s 400 Americans at the River Raisin, Michigan, on 21 January 1813. Procter was censured for recklessness and for allowing his native allies to commit atrocities but was promoted to brigadier general.

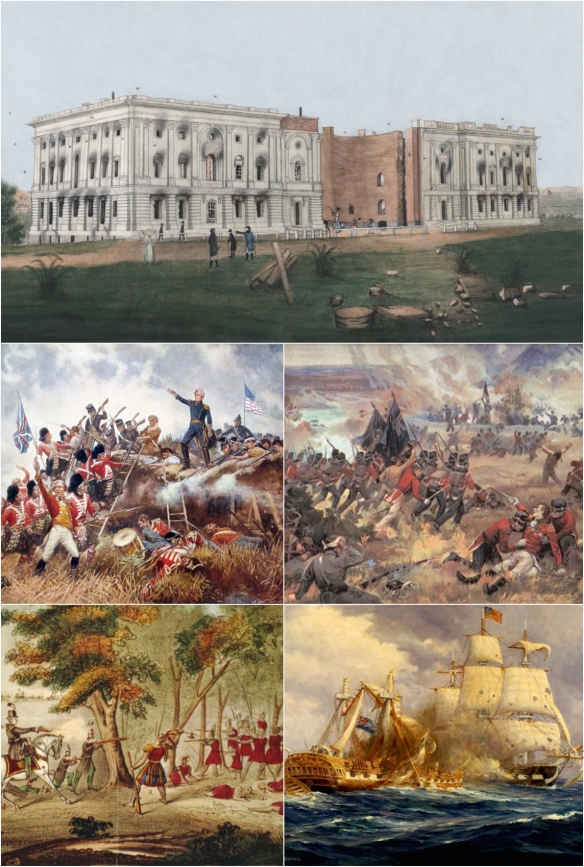

Dearborn and Brigadier General Zebulon Pike burned the capital of Upper Canada, York (now Toronto), on 27-29 April. The British burned some American matériel at Sackets Harbor on 28-29 May but failed to capture the fort. British admiral George Cockburn patrolled Chesapeake Bay, landing raiders to burn Frenchtown, Havre de Grace, Georgetown, Fredericktown, Principio, and other Maryland settlements that spring. A year later, on 14-15 May 1814, American lieutenant colonel John B. Campbell burned Port Dover, Ontario, in retaliation for the destruction of these Maryland towns.

Aided by 1,200 Kentucky reinforcements under Brigadier General Green Clay, who arrived on 5 May 1813, Harrison’s 550 defenders of Fort Meigs, Ohio, withstood siege by Procter’s 900 British regulars and 1,200 natives from 1 to 9 May. Defying Harrison’s direct order to evacuate, Major George Croghan successfully defended Fort Stephenson, Ohio, at five-to-one odds on 2 August against Procter’s attack.

On 27 May, after three days of naval shelling, 4,500 Americans under Major General Morgan Lewis took Fort George, Ontario, from Brigadier General John Vincent’s garrison of 1,900. From this dominant position, the Americans threatened the entire Niagara Peninsula. Vincent ordered other nearby forts abandoned, but on 5 June, 700 British under Colonel John Harvey surprised and defeated 2,600 Americans under Brigadier Generals William Winder and John Chandler at Stoney Creek, Ontario. On 24 June, at the Battle of the Beaver Dams, also known as the Battle of the Beechwoods, several hundred pro-British natives commanded by French captain Dominique Ducharne forced Lieutenant Colonel Charles Boerster’s column of 570 Americans to surrender. Revitalized, the British won a skirmish at Fort Schlosser, New York, on 5 July.

American brigadier general Robert B. Taylor’s 700 militiamen repelled British admiral John Borlase Warren’s and Major General Sydney Beckwith’s 4,000 amphibious invaders at Craney Island, near Norfolk, Virginia, on 22 June. However, Beckwith captured Hampton, Virginia, on 25 June and allowed his French mercenaries to rape and plunder.

Encouraged by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s naval victory on Lake Erie on 10 September and supported by Perry thereafter, Harrison took Fort Malden and Amherstburg on 27 September, recaptured Detroit on 29 September, and won at the Thames, near Moraviantown, Ontario, on 5 October. Harrison’s nemesis, Tecumseh, died in that battle.

At Chateauguay, Quebec, on 26-28 October, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry’s 1,400 French-Canadian woodsmen and militia ambushed, enfiladed, and defeated 4,500 American troops marching on Montreal under Major General Wade Hampton. At Crysler’s Farm, Ontario, on 11 November, British lieutenant colonel Joseph Morrison’s 800 regulars stopped American major general James Wilkinson’s 2,000-man expedition to Montreal dead in its tracks. A small British detachment under a Major Handcock repulsed Wilkinson at La Colle Mill, Quebec, on 30 March 1814.

Increasingly vulnerable, American brigadier general George McClure abandoned Fort George and burned the nearby town of Newark, Ontario, on 10 December 1813. The British then invaded New York, captured Fort Niagara on 18 December, massacred the inhabitants of Lewiston the same day, and burned Black Rock and Buffalo on 30 December.

Preparatory to attacking Sackets Harbor, Drummond planned to destroy the American supply depot at Oswego, New York, but the British attack on 5-6 May 1814 was only moderately successful. About 3,500 Americans under Major General Jacob Brown and Brigadier General Winfield Scott captured Fort Erie, Ontario, on 3 July. Brown and Scott defeated British major general Phineas Riall in a smart victory at Chippewa on 5 July, but Riall did stop the American invasion, halting Brown and Scott at Lundy’s Lane on 25 July, the bloodiest battle of the war. Brigadier General Edmund P. Gaines repulsed a concerted British effort to recapture Fort Erie on 13-15 August. Brigadier General Peter Porter led a successful sortie from Fort Erie against British batteries on 17 September. Brigadier General George Izard ordered Fort Erie abandoned and demolished on 5 November, ending the American military presence in Canada.

Other action during the summer of 1814 included about 300 American sharpshooters under Major Lodowick Morgan, behind earthworks at Conjocta Creek, New York, defeating 600 British under Lieutenant Colonel John Tucker on 3 August. The British occupied Eastport, Maine, on 11 July and Castine, Maine, on 1 September, and George Croghan failed to retake Mackinac on 4 August.

A 4,000-man British invading force under Major General Robert Ross routed the American defenders at Bladensburg, Maryland, on 24 August and burned Washington, D. C., that night. Ross then moved toward Baltimore. British navy captain Peter Parker died when he impulsively led a detail of 124 men ashore for a “frolic with the Yankees” at Caulk’s Field, near Chesterton, Maryland, on 30 August, and was soundly defeated by local patrols. American brigadier general John Stricker fought a delaying action against Ross at North Point on 12 September. Ross died in this engagement. His successor, Colonel Arthur Brooke, retreated from the Baltimore area after the British navy failed to neutralize Fort McHenry the night of 13-14 September. (The British repulse at Fort McHenry inspired the writing of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” but it was not officially adopted as the U. S. national anthem until 1931.)

British lieutenant general George Prevost, governor-general of Canada, led 10,000 men south in August to attack Plattsburgh, New York. Defending the area were only Brigadier General Alexander Macomb’s 3,500, since Izard’s 4,000 had been diverted toward Sackets Harbor. The Battle of Plattsburgh occurred on 11 September, coincident with the decisive American naval victory on Lake Champlain. Each side lost only about 100, but the British withdrew. Several subsidiary conflicts between the Americans and the indigenous peoples occurred during the War of 1812. The largest of these was the Creek War, fought mostly in Alabama. It began with attacks on whites at Burnt Corn Creek on 27 July 1813 and Fort Mims on 30 August. Brigadier General John Coffee destroyed Tallushatchee on 3 November, and Major General Andrew Jackson demolished Talladega on 9 November. Battles at Emuckfau on 22 January 1814, Enotachopco on 24 January, and Calibee Creek on 27 January wore the Creeks down and prepared the way for Jackson’s decisive victory at Horseshoe Bend on 27 March. The Treaty of Fort Jackson ended the Creek War on 9 August and freed Jackson for other campaigns.

As early as summer 1812, Jackson had urged a Florida campaign but was ignored. The Spanish government of Florida allowed Britain to occupy Pensacola on 14 August 1814, but Jackson captured it on 7 November. Having neutralized Pensacola’s military capability, Jackson rushed west to defend Mobile and New Orleans. Americans had already repelled one British naval attack on Fort Bowyer, guarding Mobile, on 12 September and were expecting another.

With the defeat of Napoleon, the British took counsel of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, as to the terms that they should insist upon in the continuing negotiations with the Americans at Ghent. “The Iron Duke” pointed out that the British themselves had not gained any clear-cut advantage and that they would do well to conclude the war on the basis of the status quo ante bellum. The British government took this wise advice. The war indeed ended in a virtual draw by the Treaty of Ghent on 24 December, but that news did not reach the United States until after the Americans under Jackson had inflicted on the British one of the most one-sided defeats in military history at the Battle of New Orleans on 8 January 1815, giving Americans the idea that they had somehow won the War of 1812.

All the causes of the war were moot by the time of its end: the British had no further need to interfere with American shipping after Napoleon’s defeat, the Americans had obviously failed to take any part of Canada, and with the British cutting their losses in the United States, the Americans could handle the American Indians by themselves. For the British, compared to the great struggle against Napoleon, the War of 1812 was always a sideshow. But for the Americans, the war had produced enough military heroes and legends (not to mention presidents and presidential candidates) for generations to come.

References and further reading: Adams, Henry. The War of 1812. New York: Cooper Square, 1999. Berton, Pierre. Flames across the Border: The Canadian-American Tragedy, 1813-1814. Boston: Little, Brown, 1981. Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: The Forgotten Conflict. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989. Mahon, John K. The War of 1812. New York: Da Capo, 1991. Quimby, Robert S. The U. S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1997.