It is difficult to define a “typical” battle during the Great War. Despite popular impressions of trench warfare, the nature of combat differed greatly over the course of the four years and from theater to theater. On the eastern front, the density of troops per kilometer of front was never anything akin to what it was in the west. As a result, combat on the eastern front remained more mobile. Even cavalries played an important role at times. Following the entry of Italy into the war in May 1915, the Italians and the Austrians engaged in mountain warfare along the Alpine front. The same was true in the mountains of eastern Anatolia, where the Russians and Turks fought. In the Middle East, or Turkish theater, combat was very different. The Turks and the British fought in desert or near-desert conditions in Mesopotamia and Palestine. The fighting in the Gallipoli peninsula resembled that of the western front, although the terrain was more rugged and the Commonwealth forces had their backs to the sea.

But it is the western front that people usually think of when they consider the Great War. And the nature of combat there was very different over the course of the four years of war.

In the initial, mobile stages of the war, both sides fought much as they had during the wars of the 1860s and 1870s. Formations of infantry and cavalry maneuvered about the battlefield. Troops brought firepower to bear on their opponents, sought cover where they found it, and called up their artillery howitzers in direct support. Eventually, one side was forced to retreat, and the victor moved forward.

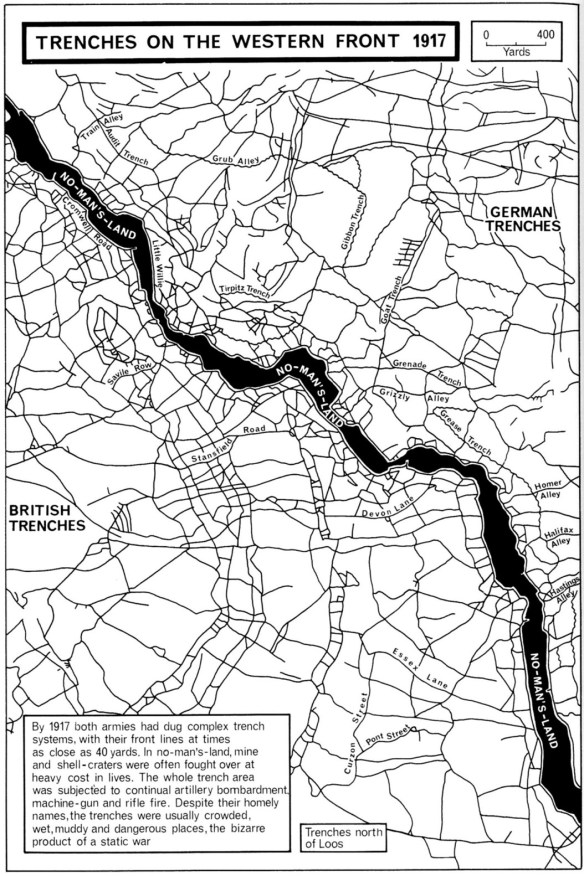

The costs of such assaults, in the face of defensive rifle and machine-gun fire and artillery, were high. Casualties were usually heavy for both victor and vanquished. Moreover, defenders soon learned that it was best to entrench, to generate one’s own cover, in order to avoid the firepower of the attacker. A successful stand by an entrenched defender led to attempts by an attacker to turn a flank. As those attempts were met, in turn, by more entrenched defenders, these temporary positions became increasingly permanent. Trench systems grew as the troops dug in and spread obstacles, such as barbed wire, in front of their positions.

Driving an entrenched enemy from the field became increasingly difficult. The flat-trajectory field howitzers that dominated early artillery arms were not much use against an entrenched enemy. Infantrymen were forced to carry the defender’s positions alone, and that drove up the costs of the attack. Eventually, those costs became prohibitive, and the armies entrenched while they waited for more reinforcements, new weapons, and new forms of artillery, such as mortars and long-range guns that fired their shells in a higher trajectory.

The new battles on the western front became what the Germans called Materialschlact—battles of materiel. In an effort to overwhelm a defender, the attacker would concentrate masses of troops and guns along a narrow sector of front, pulverize the enemy lines with a massive artillery barrage that might last for days, and then send the attacking battalions forward.

Defenders soon learned to adjust to these tactics. The lengthy preparatory barrages revealed an enemy’s intentions and allowed the defender to mass reserves to repel the coming offensive. The trench systems themselves became ever-more elaborate. Men dug deeper, building wood-, concrete-, and steel-reinforced trenches and deep, often spacious dugouts where the men could ride out the artillery barrage. The depth of systems grew as the defenders added additional lines of trenches. Rear lines housed reserves that would counterattack the assaulting force while it was still weak, disorganized, and confused, generally regaining the front line. The inability of a successful attacking force to survive a powerful counterattack by the defender’s reserve was the principal reason that the position of the trench line in Flanders so rarely moved. Over the course of the war, defenders learned to cheat—to thin out the forwardmost trench lines, the ones likely to be pulverized in the opening barrage. These trenches now became mere outposts meant to break up an enemy attack, not to stop it, and prepare the stage for the inevitable counterattack.

Amidst all of these changes, both sides began using poison gas. Early on, gas was deadly against troops who had no defense, other than to collapse in place or run toward the rear. But as the war progressed, all the armies began to issue gear that, if used properly, did protect soldiers from the gas and allow them to keep fighting. Nevertheless, with both armies wearing gas masks and other cumbersome gear, the tempo of the battlefield slowed down, a factor that could work for or against an attacker, depending on the circumstances, but that added an extra measure of horror to the Great War battlefield.

In the final stages of the war, during 1917 and 1918, both the Germans and the Allies developed new, though very different, tactical methods. Both sides realized that massive preparatory barrages did not work and surrendered the element of surprise. The Allies, especially the British, developed the “rolling” or “creeping” barrage. The artillery concentrated to support the attack would hit the front sectors for a short barrage and would then lift and move forward along preregistered lines ever more deeply into the enemy rear. The infantry would advance according to a set timetable that would bring them to a given position on the trailing edge of the barrage, so that they could assault the enemy position before the Germans could fully recover, dig themselves out of their dugouts, and set up their machine guns. It was said of the best British rolling barrages of the war that an advancing soldier would be so close to the fire that he could “light his pipe” with it.

Another British innovation, soon adopted by the French and the Americans, involved the use of tanks. These tracked armored vehicles, mounting cannon and/or machine guns, could cross the devastation of no-man’s-land, drive over obstacles such as barbed wire, brave the fire of rifles and machine guns, and provide both cover and fire support for the attacking infantry.

While such developments marked major tactical advances, they nevertheless were not the entire answer to the problems facing the Allies. Tanks tended to break down on the battlefield and could not always be depended upon to support the advance beyond the initial lines of defense. The rolling barrage worked well during the initial assault, but as the first wave of attacking battalions went forward, an increasing number would inevitably fall behind schedule as their artillery support mindlessly moved on without them. Battlefield communications remained so primitive that it was difficult, and often impossible, to make the necessary adjustments.

As a result, while Allied attacks late in the war were more successful and not as prohibitively costly as they had been earlier, they were still not cheap. Nor were they able to break through the entirety of the German defensive system until the very end, when the German army began to collapse from exhaustion and loss of hope for the possibility of victory.

Toward the end of the war, the Germans worked out their own set of tactics known as stoss (“shock”), or infiltration tactics (and occasionally and incorrectly as Hutier tactics). The Germans developed their new tactics through experience gained on all fronts and employed them first on the eastern front at Riga in September 1917, then in Italy at Caporetto in October 1917.

The keys to the new German tactics were surprise, speed, and initiative. Attacking units at the front moved only at night. Specially prepared shelters hid the new units from enemy eyes. The Germans employed a short but sharp preparatory artillery barrage using explosives and gas, followed by a rolling barrage. There was thus no need to stockpile mounds of shells that were certain to be seen by enemy reconnaissance aircraft.

Immediately behind the barrage came not masses of infantry, but small Stosstruppen. These were specially trained, organized, and equipped units. The basic unit was not the battalion, but the squad of about a dozen and a half men. Each squad included teams of men carrying light machine guns or automatic rifles and small mortars. These units were trained not to assault the entirety of the forward enemy trench line, but to search out the weak spots, bypass the strong points, and to move into the enemy rear. There they would dislocate defenses, disrupt communications lines, prevent the movement of reserves to the front, and, if all went well, achieve a breakthrough. Subsequent waves of additional Stosstruppen would be fed into the discovered gaps in the enemy defenses, while regular infantry units moved forward to mop up strong points bypassed by the Stosstruppen. The leaders of Stosstruppen units were expected make decisions on their own initiative, without receiving orders from the rear. They would, using flares and runners, identify for subsequent waves the weak spots they had found and keep moving through the enemy defenses.

The Germans unleashed their new tactics along the western front in 1918 and in a series of offensives between March and May that shattered the Allied lines, nearly breaking the British front and driving through the French toward Paris. For the first time in years, the opposing armies found themselves fighting in open terrain, areas such as Belleau Wood, where the American Marine Brigade checked the German advance toward the Marne.

But even the German tactics, while a major advance, were not the complete answer to the tactical conundrum facing Great War commanders. As the German advance progressed, the Stosstruppen eventually outran their supplies and artillery support and collapsed, exhausted. Moving supplies, guns, and reinforcements forward over the battlefield remained an unsolved problem. Poor communications bedeviled the advance. There was now more mobility on the battlefield, but not enough to bring about a decisive result. The war continued to be a contest of attrition, and one that the Germans could not win.

Nevertheless, the outlines of future warfare were becoming apparent. The marriage of German tactics, Allied armored developments, the motorization of logistic and artillery elements, wireless voice radio, and the use of aircraft in direct ground support would form the core of what in 1939 would be termed Blitzkrieg—“lightning war!”