Known to Americans during the war as the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), the People’s Army of Vietnam was the army of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Its organization included some air and naval units, but it was primarily composed of infantry units and their related support units, including artillery, armor, and logistics. It was also divided into a hierarchy of regular, regional, and self-defense forces with varying levels of equipment and training. The PAVN provided leaders, supplies, and reinforcements to the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) or Vietcong, but the two armies often operated separately and had separate identities.

The PAVN, as a military organization, was largely the creation of Vo Nguyen Giap. He was its original commanding officer, and, although other generals challenged and even eclipsed his leadership during the American war, he remained an influential and heroic figure. Giap created an armed propaganda brigade in 1944 as part of the Vietminh resistance to the Japanese. From this modest beginning, he and others built a force of mostly peasant irregulars to fight the French after 1945, and this organization became known as the People’s Army of Vietnam in 1950. PAVN leaders adopted the Chinese Communist model of protecting base areas, harassing their enemy, and avoiding set battles with the better-equipped French, but they also had organized six combat divisions by 1952. PAVN strategy against the French and later the Americans was a variant of what the Chinese called “People’s War,” but it adapted more flexibility between regular and irregular tactics than in Mao Zedong’s theories. When the PAVN scored its decisive victory over the French garrison at Dienbienphu in 1954, its assault was largely a conventional operation by regular troops.

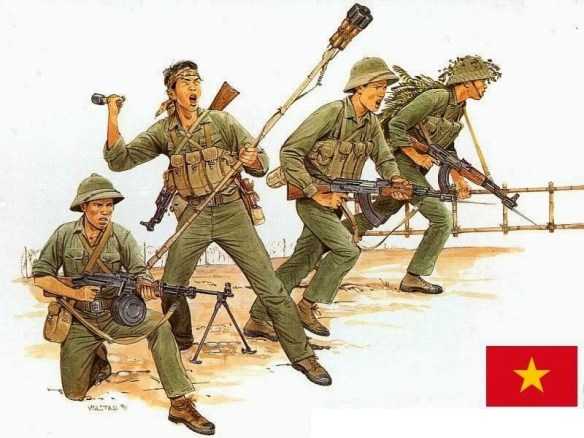

Between the French and American wars, Hanoi modernized its army and built it up to a size of about 160,000 by 1960. Aided by Chinese and Soviet advisers, the PAVN introduced standardized practices for unit organization, uniforms, ranks, recruitment, and training. It remained three-fourths infantry, but added engineering, air defense, air transport, communication, and other technological elements. The DRV also had compulsory military service, which created a large reserve pool of trained personnel. The PAVN had a good supply of soldiers but was often lacking in sufficient materiel. Consequently, it gave its troops heavy political indoctrination in the glory of patriotic sacrifice and prepared them to use guerrilla, as well as conventional, tactics as needed.

After the Politburo decided in late 1959 to aid the armed insurrection in the South, the PAVN began logistic and advisory support of the PLAF and the infiltration into the South of southern-born fighters living in the North. In 1964 units of northern-born troops were also sent into the RVN, and regular PAVN brigades eventually clashed with ARVN and U. S. forces, primarily in the Central Highlands. High PLAF losses during and after the Tet holiday fighting in 1968 required an increase in the number of PAVN troops in the South and their use in low-land areas that they previously had avoided. As the Nixon administration began lowering the number of American combat forces in South Vietnam in 1969, Hanoi felt less risk in sending more combat divisions, as well as tanks and artillery, into the RVN. The PAVN felt emboldened to launch its so-called Easter Offensive against the northern provinces of South Vietnam and isolated targets in the Mekong Delta and Central Highlands in May 1972, but it was repulsed by ARVN forces with heavy U. S. air support. In 1975, however, with U. S. air power unavailable and with the PAVN expanded to 685,000 main force troops, the DRV’s army swept through disintegrating ARVN defenses with troops, tanks, and heavy artillery and had complete control of the South by April 30.

After 1975 the PAVN continued to grow until its forces surpassed one million, making it one of the four largest standing armies in the world. In 1978 it occupied Cambodia and successfully withstood a brief clash with China’s army in 1979. The PAVN withdrew from Cambodia in 1989, and economic problems and loss of Soviet aid led to sharp cut backs in its size in the 1990s.

Vo Nguyen Giap (25 August 1911 – 4 October 2013)

As senior general in the People’s Army of Vietnam (1946-1972) and minister of national defense (1946-1982), Vo Nguyen Giap was one of the acknowledged architects of the Vietminh and DRV military successes against France and the United States. As one of the founders of the Vietminh, with Ho Chi Minh and Pham Van Dong, and a member of the Politburo from 1951 to 1982, he was also a key political leader. In fact, his military genius came from a combination of historical study of warfare and the ability to combine politics and military strategy. Born in Quang Binh Province in central Annam, he attended the National Academy in Hue but was expelled as a trouble maker. He joined the Indochinese Communist Party in 1930 and graduated from the University of Hanoi in the mid-1930s with a degree in law. He briefly taught history in Hanoi before the party sent him to southern China in 1940. He left his wife behind, and she later died a painful death in a French prison. He joined Ho in creating the Vietminh and organized an Armed Propaganda Brigade of thirty-four men who represented what would become the PAVN. His troops underwent political indoctrination as well as military training to instill high motivation. His strategic doctrine followed Mao Zedong’s model of People’s War that mixed political and military activity leading to a final offensive and political revolution.

Giap gained his fame for the dramatic PAVN siege and capture of the French fortress at Dienbienphu in 1954. During the DRV’s war against the Americans, Giap retained his leadership offices but often encountered intense debates with other commanders over strategy. He generally cautioned patience, while others wanted to be more aggressive against the U. S. forces. He designed the Tet Offensive of 1968 that produced high casualties for his own troops and no popular uprising in the South. It had enough initial success, however, to produce an unexpected psychological victory for Hanoi. Controversy continued to surround his military leadership, and before the end of the war he no longer commanded the PAVN. His political power declined as well, and after the war he was dropped from the Politburo. In his retirement the government designated him as a “national treasure.”