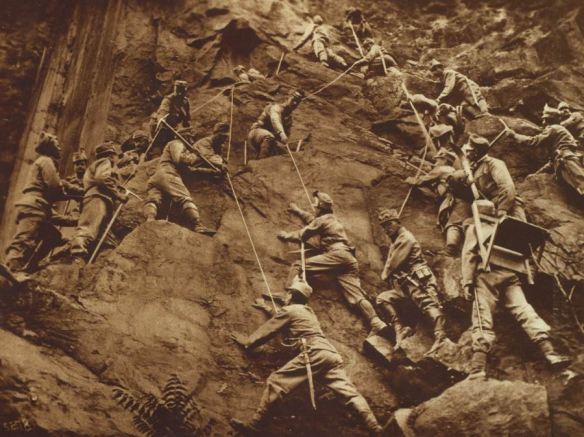

Austrian mountain troops scaling a rock face on the Italian front.

Italian alpine units climbing a steep slope during World War I.

Italian troops congregate around a mountain refuge. During WWI, for the first time in history, men brought modern technology up the highest mountains.

German Alpenkorps soldiers posing on a mountain; ca. 1915

The Alpenkorps was a provisional mountain formation of division size formed by the Imperial German Army during World War I. It was considered by the Allies to be one of the best in the German Army.

After experiencing considerable difficulties in fighting the French Chasseurs Alpins in the Vosges Mountains during the Battle of the Frontiers, the German Army determined to create its own specialized mountain units. The Royal Bavarian 1st and 2nd Snowshoe Battalions (Kgl. Bayerisches Schneeschuhbataillon I & II) were formed in Munich, Bavaria on November 21, 1914. A third battalion was formed in April 1915 from the 4th, 5th and 6th companies of the second battalion. In May 1915, the three battalions were brought together with a fourth (formed from troops of the other battalions and Bavarian Landwehr troops) to form the 3rd Jäger Regiment (Jäger Regiment Nr. 3). In October 1915, the designation Schneeschuhbataillon was eliminated.

Also in May 1915, the previously separate Bavarian 1st, 2nd and 2nd Reserve Jäger Battalions were joined to form the Royal Bavarian 1st Jäger Regiment (Kgl. Bayer. Jäger Regiment Nr. 1). The Prussian 10th, 10th Reserve and 14th Reserve Jäger Battalions were also joined together, forming the 2nd Jäger Regiment (Jäger Regiment Nr. 2).

These units, along with the elite Royal Bavarian Infantry Lifeguards Regiment (Infanterie-Leib-Regiment), the Bavarian Army bodyguard regiment, became the core of the Alpenkorps, and were complemented with additional artillery, machinegun and other support units. The Alpenkorps was officially founded on May 18, 1915 with Bavarian Generalleutnant Konrad Krafft von Dellmensingen as its commander, and Bavarian Generalmajor Ludwig Ritter von Tutschek and Prussian Generalmajor Ernst von Below as his brigade commanders.

In September 1917, the Alpenkorps was sent once more to the Italian Front to reinforce the Austrian Army for the upcoming 12th Battle of the Isonzo. By this point, the Royal Württemberg mountain battalion (“Königlich Württembergisches Gebirgsbataillon”) had been attached to the division, and one of its members, the later-Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, would distinguish himself at Caporetto in November. Another company commander who distinguished himself at Caporetto, the Infanterie-Leib-Regiment’s Ferdinand Schörner, would also rise to Field Marshal in World War II.

During World War I the 26 peacetime Alpini battalions were increased by 62 battalions and saw heavy combat all over the alpine arch.

The Alpini battalions were divided in 233 companies of 100 to 150 men each. The Alpini regiments were never sent into battle as a whole, instead single companies and battalions were given specific passes, summits or ridges to guard and defend on their own.

The war has become known as the “War in snow and ice”, as most of the 600 km frontline ran through the highest mountains and glaciers of the Alps. 12 meters (40 feet) of snow were a usual occurrence during the winter of 1915/16 and thousands of soldiers died in avalanches. The remains of these soldiers are still being uncovered today. The Alpini, as well as their Austrian counterparts: Kaiserschützen, Standschützen and Landeschützen occupied every hill and mountain top around the whole year. Huge underground bases were drilled and blown into the mountainsides and even deep into the ice of glaciers such as the Marmolada. Guns were dragged by hundreds of troops on mountains up to 3,890 m (12,760 feet) high. Roads, cable cars, mountain railroads and walkways were built up, through and along the steepest of cliffs. Many of these walkways and roads are still visible today, and many are maintained as Via Ferrata for climbing enthusiasts. In addition, along the former frontline it is still possible to see what is left of hundreds of kilometers of barbed wire.

In this kind of warfare, whoever occupied the higher ground first was almost impossible to dislodge, so both sides turned to drilling tunnels under mountain peaks, filling them up with explosives and then detonating the whole mountain to pieces, including its defenders: i.e. Col di Lana, Monte Pasubio, Lagazuoi, etc.

Climbing and skiing became essential skills for the troops of both sides and soon Ski Battalions and special climbing units were formed. It was during these years that the Alpini, their spirit and their mules became famous, although at the cost of over 12,000 casualties out of a total of 40,000 mobilized Alpinis.

Many of the famous Alpini songs originated during this time and reflect upon the hardships of the “War in Snow and Ice”.

The Kaiserschützen (English: Imperial Infantry) were three regiments of Austro-Hungarian mountain infantry during the K.U.K. Monarchy.

Established 19 December 1870 with ten Tyrolian Landesschützen (Territorial Infantry) battalions, there were two companies of mounted infantry added in 1872. In 1906 they were reorganized in the pattern of the Italian Alpini as pure mountain troops. Despite being territorial forces, the Kaiserschützen were used in the First World War in many theatres and took heavy losses.

The Battle of San Matteo took place in the late summer of 1918 on the Punta San Matteo (3678 m) during World War I. It was regarded as the highest battle in history until it was surpassed in 1999 by the Kargil Conflict at 5600m.

At the beginning of 1918 Austro-Hungarian troops set up a fortified position with small artillery pieces on the top of the San Matteo Peak, from which they were able to shell the road to the Gavia Pass and thus harass the Italian supply convoys to the front line.

On August 13, 1918 a small group of Italian Alpini (307th Company, Ortles Battalion) conducted a surprise attack taking the fortified position, half of the Austro-Hungarian soldiers were taken prisoner and the other half fled to lower positions.

The loss of the San Matteo Peak constituted a loss of face to imperial Austria, and reinforcements were immediately sent to the region while the Italians were still organizing their defence on the top of the peak.

On September 3, 1918 the Austro-Hungarian started operation “Gemse”, an attack aimed to retake the mountain. A large scale artillery bombardment, followed by the assault of at least 150 Kaiserschützen of the (3rd kuk Kaiserjäger Regiment from Dimaro) was eventually successful and the lost position was retaken. The Italians, who already considered the mountain lost, began a counter-bombardment of the fortified positions, causing many victims among both the defending Italian and the Austro-Hungarian troops.

The base of the peak lies at 2800m altitude and it takes a four-hour ice climb up a glacier to reach the top.

The Austro-Hungarians lost 17 men in the battle and the Italians 10. This was the last Austro-Hungarian victory in World War I. The Armistice of Villa Giusti, concluded on November 3, 1918 at 15:00 at Villa Giusti (near Padua) ended the Alpine War in these mountains on November 4, 1918 at 1500 h.

In the summer of 2004 the ice-encased bodies of three Kaiserschützen were found at 3400m, near the peak