King Henry V’s, pictured top right at Battle of Agincourt

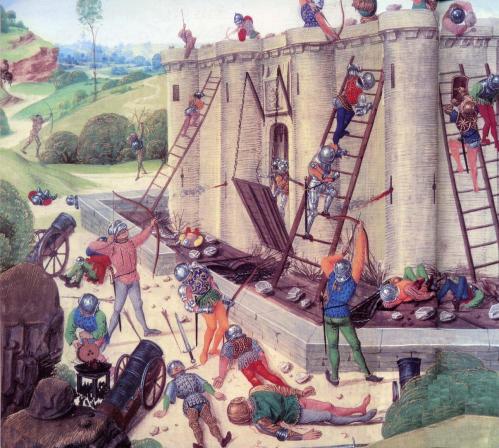

The Battle of Formigny (15 April 1450), a decisive victory for the French.

Henry V inherited a realm that was sufficiently peaceful, loyal, and united for him to campaign extensively in France (from 1415) and to spend half of the next seven years abroad. With experience of war and government as Prince of Wales, he proved a capable, fearless, and authoritarian monarch who abandoned the careful ways of his father. Even during his absences in France, his kingship was firm and energetic, enabling him to wage a war that was as much a popular enterprise as Edward III’s early campaigns had been. His reign was the climax of Lancastrian England.

Henry prepared for war by conciliating surviving Ricardians and renewing foreign alliances. The condition of France, with an insane king and quarrelsome nobles, encouraged his dreams of conquest. By 1415 he felt able to demand full sovereignty over territories beyond Edward III’s vision and even to revive Edward’s claim to the French Crown. Henry’s ambitions coincided with his subjects’ expectations. Large armies were raised under the leadership of enthusiastic magnates and knights; the realm voted taxation frequently and on a generous scale, and the king was able to explain his aims publicly so as to attract support. He even built a navy to dominate the Channel. This enthusiasm hardly faded at all before his death, though the parliamentary Commons expressed (1420) the same unease about the consequences for England of a final conquest of France as had their forebears to Edward III.

Henry V’s strategy was Edward’s – to ally with French nobles to exploit their divisions and press his own dynastic claim. Throughout the war, Burgundy’s support was essential to English success. Quite soon, however, the invader’s aims broadened into conquest and colonization on an unprecedented scale. The 1415 expedition tested the water and the victory at Agincourt strikingly vindicated traditional English tactics. In 1417-20, therefore, Henry set about conquering Normandy which, along with adjacent provinces, was the main theatre of war during and after Henry’s reign. The treaty of Troyes (1420) with Charles VI made him regent of France and heir to the Valois throne in place of the Dauphin. This extraordinary treaty dictated Anglo-French relations for more than a generation. Though Henry V never became king of France (he predeceased Charles VI in 1422), his baby son, Henry VI of England and, to the Anglophiles, Henry II of France, inherited the dual monarchy. It would require unremitting effort to maintain it.

Henry V and John, duke of Bedford, his brother and successor as military commander in France, pushed the Norman frontier east and south during 1417-29 and they defeated the French successively at Agincourt (1415), Cravant (1423), and Verneuil (1424). This was the high point of English power in France. Under Bedford, a `constructive balance of firmness and conciliation’ sought to make both the conquered lands and further campaigns (southwards in Anjou and Maine) pay for themselves. But the French resurgence inspired by Joan of Arc and the coronation of Charles VII at Rheims (1429) foiled this plan, and the English advance was halted after the defeat at Patay. Thereafter, the Normans grew restless under their foreign governors, England’s Breton and Burgundian allies began to waver, and the English Parliament had to find yet more cash for the war in northern France where garrison and field armies were an increasingly heavy burden. The English were in a military as well as a financial trap – and without the genius of Henry V to direct them.

Henry VI and the Search for Peace

During the 1430s the search for peace became more urgent, particularly in England. The Congress of Arras (1435) and discussions at Gravelines (1439) were unproductive, largely because English opinion remained divided as to the desirability of peace and the wisdom of significant concessions. But the recovery in Charles VII’s fortunes, the mounting cost of English expeditions to defend Lancastrian France, Bedford’s death in 1435, and especially the defection of Burgundy were decisive factors. The government freed the duke of Orléans (a captive in England since Agincourt) to promote peace among his fellow French princes (1440), though he did not have much success. In 1445 Henry VI married the French queen’s niece, Margaret of Anjou, but even that only produced a truce, and a proposed meeting of kings never took place. Eventually, Henry VI promised to surrender hard-won territory in the county of Maine as an earnest of his personal desire for peace. His failure to win the support of his subjects for this move – especially those magnates and gentry who had lands in France and had borne the brunt of the fighting – led to the exasperated French attacking Normandy in 1449. Their onslaught, supported by artillery, was so spectacularly successful that the English were defeated at Rouen and Formigny, and quickly cleared from the duchy by the end of August 1450: `… never had so great a country been conquered in so short a space of time, with such small loss to the populace and soldiery, and with so little killing of people or destruction and damage to the countryside’, reported a French chronicler.

Gascony, which had seen few major engagements under Henry V and Henry VI, was invaded by the triumphant French armies, and after their victory at Castillon on 17 July 1453, the English territories in the southwest were entirely lost. This was the most shattering blow of all: Gascony had been English since the twelfth century, and the long-established wine and cloth trades with south-west France were seriously disrupted. Of Henry V’s `empire’, only Calais now remained. The defeated and disillusioned soldiers who returned to England regarded the discredited Lancastrian government as responsible for their plight and for the surrender of what Henry V had won. At home, Henry VI faced the consequences of defeat.

Within three weeks of Castillon, Henry VI suffered a mental and physical collapse which lasted for 17 months and from which he may never have fully recovered. The loss of his French kingdom (and Henry was the only English king to be crowned in France) may have been responsible for his breakdown, though by 1453 other aspects of his rule gave cause for grave concern. Those in whom Henry confided, notably the dukes of Suffolk (murdered 1450) and Somerset (killed in battle at St Albans, 1455), proved unworthy of his trust and were widely hated. Those denied his favour – including Richard, duke of York and the Neville earls of Salisbury and Warwick – were bitter and resentful, and their efforts to improve their fortunes were blocked by the king and his court. Henry’s government was close to bankruptcy, and its authority in the provinces and in Wales and Ireland was becoming paralysed. In the summer of 1450, there occurred the first popular revolt since 1381, led by the obscure but talented John Cade, who seized London for a few days and denounced the king’s ministers. The king’s personal responsibility for England’s plight was inevitably great.