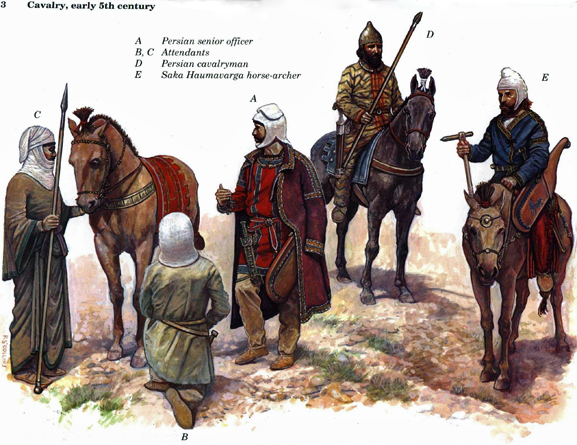

Achaemenian Asabari (Cavalry) Early 5th Century

L – R: 2 Asabari Attendants, Hazarabam (Colonel), Asabari Spearman, Saka Horse Archer with Sharp Hammer at 5 BC

The Persian army was made up mostly of light troops of varying types, nearly all of which were in large numbers (the population of the Empire was immense, both due to sheer land area and relatively dense populations in some regions). Equipment varied greatly depending on where the soldiers originated from, since each man fought according to the national style (and in the national costume) of his homeland.

A large number of archers were included in the foot troops, drawn from territories across the Empire. The sheer number of arrows they could fire meant they were a deadly component to the army, if vulnerable when caught in a melee. The infantry was scarcely better off, often fighting in nothing more than soft clothes. Nonetheless, they were extremely numerous.

No documentary evidence from the Medes themselves has been found. Few confidently identified Median sites have been excavated, and many questions remain about those that have been. Simply identifying a “homeland” of the Medes is a difficult task. The modern city of Hamadan, ancient Ecbatana, served as a capital, which we know from later traditions about Cyrus the Great’s victory over Astyages. Median settlements are mentioned in Assyrian sources, starting from the ninth century, throughout the central and northern Zagros Mountains, especially along the Great Khorasan Road towards modern Tehran.

We are thus beholden to Herodotus’ account of the rise and organization of the Median Empire, although he was not unique in his consideration of the Medes’ importance. Despite the problems with Herodotus’ portrayal, until recently it had been generally accepted – at least in outline – as an accurate rendition of the Medes’ rise to power. It has thus served as the basis for the picture of the Median Empire that is so prominent in modern scholarship. This is despite its clearly literary elements, and despite the fact that it is hopelessly conflated chronologically. In other words, Herodotus’ account of the Medes must be considered more legend than history. Nevertheless, read carefully, Herodotus has things to teach us about the Medes. If for no other reason than a lesson in historiography, a sketch of Herodotus’ telescoped tale (1.96–106) is useful.

A Mede named Deioces had designs on taking power, and he took advantage of the general lawlessness of the land. His reputation for justice brought more and more Medes to him to settle their disputes. As his influence grew, Deioces then stepped back; he refused to neglect his own affairs for the benefit of others. When lawlessness soon increased, the Medes decided to make Deioces their king. Once he had accepted the job, Deioces insisted on a bodyguard of spear-bearers and a fortified capital: Ecbatana, constructed with multiple walls, two of which purportedly had battlements plated in silver and gold (1.98). Deioces consolidated his position and then removed himself from sight, thereby making himself exceptional and emphasizing the august status of the king. He further secured his position by implementing certain behavioral protocols, for those few who did gain audience, and by establishing a network of spies and informers. This description matches in theme and outline accounts of the rise of tyrants in Greek city-states, though taken to another, grander level. With regard to the king’s exceptionality and the behavioral protocols, historians have noted the parallels with the later Achaemenid court, or rather, the Greeks’ stereotypical image of it. Many scholars thus take for granted the literary quality of Herodotus’ account of Deioces’ rise.

To resume the story, Deioces’ successor Phraortes subjugated the Persians and battled the Assyrians. Herodotus then notes a Scythian invasion, which put on hold (for twenty-eight years) the reign of Cyaxeres, who was Phraortes’ successor. Despite numerous ingenious attempts, modern scholars have not been able to reconcile large-scale Scythian invasions anywhere in the Near East in the late seventh century BCE. Assyrian evidence testifies to the Scythians’ and Cimmerians’ threat roughly a generation earlier, during the reign of Esarhaddon. But there is no Assyrian or Babylonian evidence for a “Scythian interlude” during Cyaxeres’ rule of the Medes. If this interlude is not simply a literary device, which is the most likely explanation, it seems that Herodotus or his sources conflated the history and chronology of this part of the narrative.

It is important at this point to extend the discussion of the early Medes beyond Her odotus and the Greek tradition. In the last decade, an increasing number of scholars have come to assert that even the outline of Herodotus’ account of the Medes, not just the particulars, is inaccurate. With an increase in the accessibility of Assyrian information on the Medes, reconsiderations of this important people and their place in ancient Near Eastern history are currently underway. Assyrian royal inscriptions and correspondence of the eighth and seventh centuries, until circa 650, provide a wealth of detail about the Medes and their interactions with Assyria. Some patterns have emerged. First, the Medes mentioned dwelled in fortified settlements, each headed by a city-lord (the Akkadian term bel ali). Assyrian incursions into Median territory were undertaken to control important commercial routes and to capture horses, for which the Assyrian appetite – to ride, not to eat – was insatiable. There is a striking consistency in Assyrian texts in descriptions of Medes as horsemen, and on sculptures of Sargon’s palace at Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad in Iraq) the Medes are all portrayed with horses. By the end of the eighth century, many areas, especially along the Great Khorasan Road, that the Assyrians identified as “Median” were incorporated into the Assyrian Empire. The Median city-lords of these now Assyrian-held territories were bound to the Assyrian king by loyalty oaths. Evidence for the Medes becomes sparse during Ashurbanipal’s reign (669–c. 630 BCE). It is precisely in that period in which we would expect to find a fledgling Median Empire, if such an empire existed. But Assyrian sources for the three decades before Assyria’s collapse in the 610s are thin in detail, which makes historical assessment problematic.

The Assyrian evidence is not easily reconciled with the Greek tradition. Through the mid-seventh century, there is no indication of a centralized, Median authority, that is, a sole king, one who could be equated, for example, with Herodotus’ Deioces. Modern scholars have attempted to identify some Medes named in Assyrian sources with those of early Median kings mentioned in the Greek tradition. Median local rulers Dayukku (late eighth century) and Kashtaritu (early seventh century) have been equated with Herodotus’ Deioces and Phraortes, respectively, but beyond the linguistic gymnastics involved the historical context of each does not offer a good fit. Even if Dayukku and Kashtaritu left an imprint on subsequent Median tradition through oral traditions long since lost, there is no way to forge the two perspectives, Assyrian and Herodotean, into agreement.

What remains in the dark is the critical period circa 650–550 BCE, when the Medes were at the height of their power. It remains unclear how we are to move from Assyrian descriptions of the Medes as seemingly independent city-lords to the Medes as a unified force that Cyaxeres (Umakishtar in the Babylonian sources) was able to unleash against Assyria with such devastating effect in the 610s. Recent approaches have postulated that the Medes were the leaders of a large coalition of mostly Iranian peoples from across northern Iran, a coalition unified by a forceful personality such as Cyaxeres and only for the purpose of defeating Assyria. This coalition, in conjunction with the Babylonians, was successful at that task, but afterwards the coalition splintered. If this reconstruction is accurate, it remains to be reconciled with accounts of the Medes as a major power through the first half of the sixth century, an impression given not only by Greek sources but one alluded to in Babylonian and biblical traditions (such as Jeremiah 25:25–26 and 51:27–28) as well.