PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Irish convicts vs. British colonial authorities in Australia

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): New South Wales

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: The convicts, feeling unjustly imprisoned, rebelled, seeking to escape the penal colony.

OUTCOME: The rebellion was suppressed and its leader publicly executed.

APPROXIMATE MAXIMUM NUMBER OF MEN UNDER ARMS: 266 convicts; 56 colonial troops

CASUALTIES: Convicts, 15 killed in combat, 8 executed; colonial troops, none

The history of the British penal colonization of New South Wales begins in 1788, when the first 730 convicts arrived at Botany Bay and settled at Port Jackson. Although there are different opinions as to what use the British had for the continent down under, the employment of penal colonies as a source of cheap labor in farming and development was certainly one of them, occupying a prominent place in Britain’s colonial policy in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Sydney Cove became the penal colonies’ operations center for the British, and around it flourished smaller farming penal colonies.

In 1803, Lieutenant Colonel David Collins (served as Tasmanian governor, 1804-10) arrived in Port Phillip

(near present-day Melbourne) from England with 308 prisoners. Because of the adverse conditions at Port Phillip, Collins petitioned the king for permission to relocate to Van Dieman’s Land, the present-day island of Tasmania. Once granted, a penal colony was developed in Sullivan’s Cove, the modern Hobart Town, Tasmania. The penal colony of Sullivan’s Cove was made up of Irish criminals and political prisoners, many of whom had never been tried. Such injustices led to an uprising on March 4, 1804.

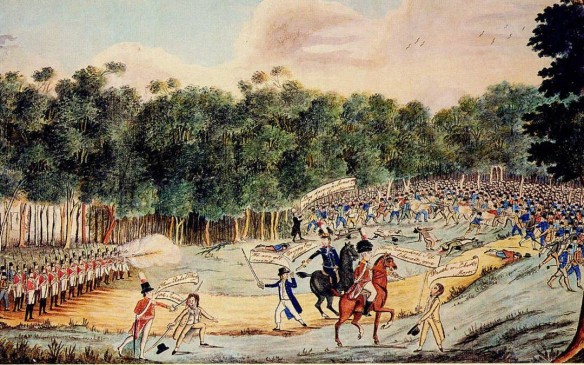

The Australian Irish Convict Revolt began at a penal farm outside Sydney called Castle Hill. Some 266 Irish convicts broke out, ransacked a nearby settlement, and, armed with farm tools and guns, rallied around their leader, Philip Cunningham (d. 1804). Cunningham had developed a plan to escape New South Wales by taking the town of Parramatta. That evening the British declared martial law and detached Brevet Major George Johnston and Lieutenant Colonel William Paterson with their troops to Parramatta. By the morning of March 5 they arrived, having marched 20 miles overnight. There ensued an unsuccessful round of negotiations, followed by gunshots. The revolt was quelled easily enough: 15 convicts were killed in the fighting and Cunningham was detained.

On March 6 the Irish rebel leader was hanged along with seven others. Nine convicts were transported to Newcastle after being flogged, and all Catholic worship was suspended in the colony. British authority had been fully restored in the region.

Further reading: Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia’s Founding (New York: Random House, 1986); A. G. L. Shaw, Convicts and Colonies: A Study of Penal Transportation from Great Britain and Ireland to Australia and Other Parts of the British Empire (Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 1977).