Battle of Buena Vista

When Taylor learned that additional Mexican troops were crossing to the north side of the Rio Grande, he withdrew most of his force to Point Isabel on the Gulf of Mexico and waited for supplies and reinforcements.

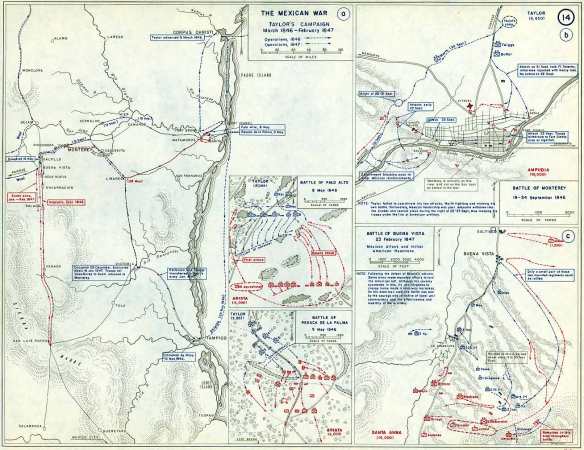

On May 7, 1846, after receiving the anticipated supplies and reinforcements, Taylor started back toward Matamoros with 2,228 officers and men, followed by 270 ox- and mule-drawn wagons loaded with supplies. On May 8, he encountered 3,709 Mexicans, commanded by General Mariano Arista, blocking the road at Palo Alto, ten miles northeast of Matamoros. The Mexican force formed a mile-long line perpendicular to the road.

Cannon fire began immediately. Solid Mexican cannonballs often fell short of the U. S. line and rolled by like bowling balls, permitting the Americans to dodge them. Horse-drawn U. S. cannons were advanced at full gallop, fired on the Mexican line, and then moved to another position. U. S. artillery was not only more mobile than that of the Mexicans, but it fired explosive shells and had greater range. Mexican attempts to advance on Taylor’s force failed due to marshy ground, dense vegetation, and withering cannon fire. After suffering some 257 casualties, mostly resulting from cannon fire, the Mexicans withdrew.

The next day the Mexicans regrouped at Resaca de la Palma, three miles north of the Rio Grande. The Resaca was an old channel of the Rio Grande, roughly ten feet deep and 200 feet wide. Since brush covered the area, the battle differed from Palo Alto. The dense chaparral prevented effective use of artillery. Combat involved small parties and hand-to-hand fighting. The outcome of the battle was still in question until U. S. troops found a trail around the west end of the Mexican line. When they appeared at the Mexican rear, the Mexicans broke and ran for the Rio Grande. The retreating force abandoned eight cannons and General Arista’s baggage, writing desk, silver service, and papers.

Matamoros, on the south side of the Rio Grande, was fortified. However, Mexican troops withdrew, permitting U. S. forces to enter it on May 18, 1846, without firing a shot. Upon occupying the city, the Americans found 400 sick and wounded Mexican troops that Arista had abandoned.

On July 7, 1846, nearly two months after the occupation of Matamoros, Mexico declared war. The first article of the declaration stated, “The government, in legitimate defense of the nation, will repel aggression initiated by the United States of America and sustained against the Mexican republic, which has had several of its states invaded and attacked.”

A few locally procured ox-carts, 175 wagons, 1,500 Mexican pack mules, and shallow-draft steamships that had been plying the Ohio and Mississippi rivers moved Taylor’s force eighty miles up the Rio Grande to Camargo, the head of navigation. His force, which had swelled to 15,000, spent four miserable months there in mud from a recent flood and heat as high as 112 degrees Fahrenheit. Estimates place the number of deaths resulting from poor sanitation there at more than 1,000. A lack of supplies, not Mexican resistance, delayed Taylor. Since the United States was not on a war footing, supplying Taylor’s army required a massive logistical effort. The supplies necessary for an offensive did not arrive until September. Even then, Taylor only had supplies to outfit 6,230 men when he began his advance.

Taylor’s first major objective was Monterrey, a city of 10,000, which guarded a key mountain pass through the Sierra Madre Oriental. Beyond that pass lay Saltillo and the interior of Mexico. The Americans faced a difficult task, as the city was protected by a river to its south, mountains to the west, and by fortresses to the north, east, and west. The 7,303-man Mexican force in Monterrey outnumbered Taylor’s force.

After meeting stiff resistance in the city, Taylor settled for less than total victory. He agreed to permit the Mexicans to retreat to Saltillo with their arms, rather than fighting to the last man. Taylor’s forces were running low on ammunition and had suffered 120 killed and 368 wounded, or 8.5 percent of the men fighting. This exceeded the Mexican casualty rate of 5 percent.

While Taylor was waging his campaign, Polk attempted to end the war through non-military means. Santa Anna, then in exile in Cuba, sent his confidential representative Alexander Atocha to Polk with a deal. Atocha claimed that if Polk would permit Santa Anna to pass through the U. S. blockade at Veracruz, Santa Anna would save lives and money by arranging for the cession of territory and a peaceful settlement of the conflict.

Polk accepted Atocha’s proposal and ordered that Santa Anna be allowed to sail from Cuba to Veracruz. In August of 1846, Santa Anna landed at Veracruz and then made a triumphal entry into Mexico City, only two years after he had been exiled “for life.” In the previous two years, Mexico had had four different governments and even more finance ministers, none of whom had enjoyed any credibility. The nation needed a savior and looked to Santa Anna, who once again received an invitation to serve as president.

Two weeks after his arrival in Mexico City, on September 28, 1846, Santa Anna ordered the Mexican army north toward Taylor’s force. This act added Polk to the long list of those betrayed by Santa Anna.

Santa Anna paused in San Luis Potosi to gather supplies and additional troops. The Mexican force that had defended Monterrey joined him. Rather than defending Saltillo, Santa Anna had ordered the troops who left Monterrey to regroup in San Luis Potosi. A lack of money hampered Santa Anna’s efforts. The refusal of the states of Jalisco, Durango, and Zacatecas, which in the past had opposed Santa Anna, to supply men and matériel presented yet another obstacle.

After four months in San Luis Potosi, Santa Anna decided to attack Taylor’s force. This decision was based on a captured U. S. dispatch that revealed that much of Taylor’s army had been withdrawn to take part in a planned amphibious landing at Veracruz. On January 27, 1847, Santa Anna’s force started north, some 21,553 strong-another tribute to his organizational capacity. In twenty-seven days, his force marched 240 miles and decreased to 15,142, not due to hostile fire, but cold weather, poor food, and desertion. A large contingent of soldaderas, who prepared food, maintained clothing, provided medical care, and on occasion, engaged in combat, accompanied the force north. Their presence was a major factor in stemming desertion.

Santa Anna’s still formidable force approached Taylor’s position ten miles south of Saltillo. Each nation engaged gave the battleground where they met different descriptive names. To the Americans, the place was Buena Vista, referring to the fine view south from the high plateau that the Americans were defending. The Mexicans called the battlefield Angostura (the narrows), referring to the narrow pass through which the Saltillo-San Luis Potosi road passed. Mountains lined the road to both the west and east. Steep gullies crisscrossed the area alongside the road, forming a natural barrier.

The ensuing battle lasted two days, February 22 and 23, 1847. On one occasion, the Mexicans broke through the east side of the U. S. line. Reinforcements thrown into the breach saved the Americans. Later Mexican attacks were turned back by light artillery, which proved decisive due to its ability to shift rapidly to check Mexican infantry advances. Finally, after two days of hard fighting and heroism on both sides, Santa Anna’s forces turned back. Taylor lost 272 killed, the highest U. S. death toll of any battle in the war, and 387 wounded, or about 14 percent of the men engaged. The Mexicans lost more than twice that number. Although Taylor’s 4,594-man force was mainly composed of green volunteers, they were well rested, well fed, and enjoyed effective artillery support.

Had Santa Anna persisted a third day, he might have broken through U. S. lines. However, he decided his men were incapable of fighting for another day. Rather than risking a decisive defeat, Santa Anna pulled his men back. He justified quitting a battlefield where he claimed to have won, noting that his troops had not eaten or slept in forty-eight hours and were dying of thirst, hunger, and fatigue. Strategically the battle accomplished little, since both armies returned to their initial positions, Santa Anna in San Luis Potosi and Taylor in Saltillo. However, the battle did stir the fires of patriotism in the United States as reports arrived of Taylor’s turning back of Santa Anna’s superior force.