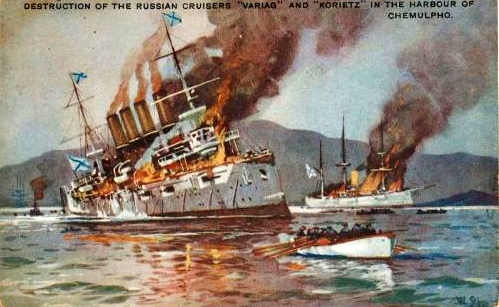

The attack on Port Arthur, sometimes referred to as history’s first Pearl Harbor, was bold in conception but poorly executed. During the evening hours of 8 February 1904, Admiral Togo dispatched three torpedo boat flotillas against the seven Russian battleships anchored in the unprotected outer roadstead at Port Arthur. This surprise attack represented only part of a grand plan to seize command of the sea immediately and unexpectedly at the war’s outbreak. Another flotilla was dispatched to attack Dalian (Russian Dal’nii), a Russian commercial port 60 kilometers north. Meanwhile, at dawn on 9 February Japanese cruisers escorted a convoy carrying 2,500 troops into the approaches to the Korean port at Chemulpo (Inchon). After a brief and lop-sided engagement, the Russian cruiser Variag and gunboat Koreets were forced to scuttle themselves rather than surrender. The way now lay open for accomplishment of an important Japanese objective, the establishment of the first of several beachheads in Korea.

Another Japanese surprise attack actually preceded the more famous torpedo strike at Port Arthur. The Japanese also attacked the port of Chemulpo (Inchon) in Korea, targeting two Russian vessels. Obviously these ships needed to be destroyed for the Japanese to land soldiers in the city. Togo assigned a strong force of cruisers to this task, calculating that they could easily overwhelm an unarmored Russian cruiser and an obsolete gunboat. The more difficult part of the assignment was ensuring the destruction of the Russian ships without harming any other ship belonging to a neutral power. These crowded the harbor. To solve this problem, the Japanese commander, Rear Admiral Uriu, summoned the Russians to sea for an engagement. He warned all parties that the Japanese would enter the harbor and attack the Russian ships should his ultimatum be rejected. Neutral ships would be responsible for themselves should the Japanese have to take this step. Captain Stefanov, the senior Russian officer, accepted his fate and led his ships to battle. Hopelessly outmatched, he returned to the harbor an hour later, both ships badly damaged but still afloat. The Japanese closed in to finish him off, prompting the Russians to scuttle their ships. A short time later, Japanese infantry disembarked in Chemulpo.

To win the war, Togo had either to eliminate or to contain the Russian Pacific Squadron and to transport the Japanese army and its supplies safely to Korea and Manchuria. His primary mission was to attain and maintain control of the sea in the theater of operations. Because Togo’s capital ships constituted his most valuable and irreplaceable asset, he could not expose them directly to the coastal artillery and minefields of Port Arthur. First, he needed to sting the Russian battleships to reduce the odds, then entice them into the open sea for a Mahanian-style main-force shoot-out. During the chilly night of 8-9 February 1904, five Japanese torpedo boats succeeded in approaching the Russian Pacific Squadron at anchorage in Port Arthur’s unprotected outer roadstead. They loosed 19 torpedoes, three of which hit their targets. The Retvizan and Tsesarevich were holed, but not mortally, while the Pallada suffered serious damage. Thus, the Russo-Japanese War began with Togo’s election initially to pursue a cautious strategy of attrition and containment. Although he was wresting control of the sea from the Russians for freedom of Japanese naval movements, his inability to eliminate the Russian Pacific squadron produced a classic example of the baleful effect of “a fleet in being.” Even bottled up, the Russian squadron would become the bane of Togo’s existence, and more importantly, the primary rationale for later bloody ground assaults against Port Arthur.

Events on 9 February revealed just how seriously the Japanese accepted their quest for control of the sea. Across the Yellow Sea at Chemulpo two Russian vessels, the cruiser Variag and the gunboat Koreets, monitored local developments and exercised presence. Cut off from telegraphic communications, they came under fire from Admiral Uriu Sokichi’s superior cruiser force, including the Asama. After a brief, lop-sided duel that left the Variag burning, the Russians were forced to scuttle their ships. Uriu’s mission was to convoy landing troops that would form the backbone of General Kuroki Tametomo’s invading First Army. Kuroki’s mission was to link up with Japanese troops coming from Pusan and other ports for an overland march to the Yalu. With the issue at Port Arthur still in doubt, Korea must be secured before the Russian army could move south from Manchuria. Otherwise, the kingdom might become impossible to retake once Russian occupiers had entered the peninsula in force. Moreover, Kuroki’s army was to become one of the tentacles that would eventually assail Russian troop concentrations in Manchuria.

The film, The Cruiser Variag, directed by Viktor Eisymont according to Georgii Grebner’s screenplay, occupies a special place in the collective memory of the Russo-Japanese War. Like Pikul”s novel, the movie was produced by the generation of victors. It was shot in 1946, riding a wave of patriotic fervor generated by the Soviet’s and its Allies’ triumph in the Second World War. This was the brief moment when love of the motherland had not yet been distorted by the Kremlin’s campaign against “cosmopolitanism and obsequiousness,” and when military history could be seen as elements of the USSR’s heritage rather than “the gloomy era” of tsarism.

It goes without saying that such a film could not have been made without approval at the highest political level. The studio was even permitted to cast as the Variag one of the holiest Soviet vessels, the Aurora, which also participated in the Russo-Japanese War and survived the Battle of Tsushima. Even to the modern viewer there is a contrast between the officers portrayed in the movie and the stereotypes of the Short Course, as well as of the novels of Novikov-Priboi and Stepanov. In the former the entire officer corps, from the most junior midshipman to the captains of the Variag and the Koreets, Rudnev and Beliaev, appears in an entirely favorable light. Whereas Soviet films typically portrayed priests negatively, in this production, the Variag’s chaplain is a “spiritual doctor,” an intellectual who not only understands Asian languages, but is capable of interpreting the most complicated Chinese poetry. The officers and the sailors operate more as a brotherhood rather than a strict hierarchy, and join together in the evening to sing Russian folksongs and to engage in spirited discussions about the Motherland and duty.

The question “Who is guilty?” is answered only indirectly: Higher command was responsible both for war and defeat. To avoid any uncomfortable parallels with Germany’s surprise attack on 22 June 1941, not one word was spoken about the central government or the emperor. The entire blame was squarely placed on the shoulders of the staff, which on the eve of the war only asked the Variag for “reports, threads, buttons and wax,” and expected only an urgent despatch wishing the wife of the Pacific Squadron’s commander a happy name-day (a reference to the mythical ball held at the Navy Club in Port Arthur). The director’s dominant cinematic metaphors include the St. Andrew’s standard-Captain Rudnev-Russia-faithfully fulfilling one’s duty-refusing to surrender to the enemy. 28 They contrast dramatically with the themes that dominate the Short Course (the attempt to head off revolution-Japan’s unexpected attack- incompetent and corrupt generals-defeat-the ignominious peace), although they do not contradict them outright. Consequently, there was no major change in the popular consciousness about the war. At the same time, the film Variag anticipated the “intelligent, patriotic line” adopted about the Russo-Japanese War by Pikul in The Cruisers as well as in textbooks, such as the aforementioned In Service of the Motherland.

Many attribute Moscow’s decision to decorate surviving veterans of the Battle of Chemulpo on the occasion of its 50th anniversary to the film’s influence. On 8 February 1954 they were awarded a medal inscribed “For Courage” (Za otvagu) and-characteristically- “For the Victory over Japan.” None of those who participated in the siege of Port Arthur or in the Battle of Tsushima were honored, surely a testimony to the “prejudicial” power of film and literature. During the same year work began on a monument to the Variag’s commander, Admiral V. F. Rudnev, in Tula (nor far from the Rudnev estate in the village of Savino). Completed in 1956, the statue is one of the most popular memorials to the Russo-Japanese War. Every year, on the anniversary of the Variag’s last battle, flowers are left at its base, and navy veterans gather at the site. To this day, the best naval conscripts of the Tula District are sent to serve on the current Variag, the Pacific Fleet’s flagship. Tula is something a regional center for the memory of the Russo-Japanese War.