Kohima, an attractive little town, was situated on a ridge of small hills approximately halfway along the road from the important rail and supply depot at Dimapur to the larger garrison town of Imphal. Although it lay on a high ridge – about 5,000 feet – it was surrounded by massive mountain ramparts rising, like Mount Pulebadze on the south-west, to more than 10,000 feet. The Dimapur road, as it approached Kohima, climbed a steep hill and passed the site of the Indian General Hospital (IGH Spur). The Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow, in its attractive, spacious and colourful grounds, dominated the centre of the town. These grounds, like most of Kohima, had been terraced, with a substantial drop between each terrace – so at different levels there were the DC’s bungalow, the tennis court and the Club. The bungalow looked south over a series of small hills which had recently been developed by the army as a supply base: first Garrison Hill; then Kuki Piquet; then the Field Supply Depot (FSD), where there were several more substantial bashas (bamboo huts), with, for example, a row of large ovens; and finally the Daily Issue Store (DIS). The Deputy Commissioner, Charles Pawsey, had been in the area for 20 years and had built up a remarkable rapport with the local Naga people who lived in the welldefended hill-top villages in the surrounding area. Pawsey and his loyal Nagas were to play a significant part in the battle of Kohima.

The Royal West Kents moved out of Kohima on 31 March, leaving Richards with `a few odds and sods’ – a company of Gurkhas, a company of the Burma Regiment and a few other minor units. Rations and ammunition, of which fortunately there was plenty, were issued, but the supply of water was precarious. There were some large metal tanks near the DC’s bungalow, but these were extremely vulnerable. Richards was told to hold Kohima for as long as possible, and was promised that the survivors of the Assam Regiment from the battles at Jessami would come to his assistance. Richards had sent urgent demands for barbed wire, essential for the defence of every type of position, but – just as at Sangshak – the front-line units about to be attacked received none. In desperation Charles Pawsey, who throughout the siege wore grey flannel trousers and an open-necked shirt, got his Nagas to sharpen wooden stakes to protect the bunkers.

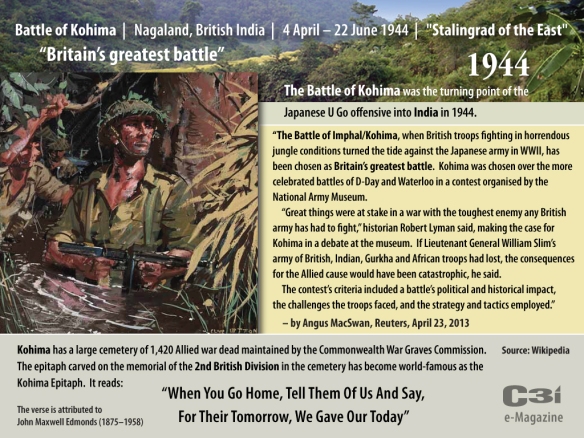

By 4 April, when the first units of 2nd Division were arriving at Dimapur, Stopford conferred with Ranking and Major-General Grover (GOC 2nd Division). Seeing the build-up at Dimapur, Stopford decided he could afford to send 161st Brigade back to Kohima. The fury, the frustration and the language of the soldiers involved can be imagined. As the Royal West Kents advanced again up the Kohima road they met hordes of panic-stricken soldiers and civilians. They relieved them of any arms and ammunition, but allowed them to go on. Lieutenant- Colonel Laverty decided that, although the Japanese were at the outskirts of the town, his battalion would advance as rapidly as possible into Kohima. As they arrived, accurate Japanese shelling began, destroying much of their kit and most of their trucks. This was the unpromising start to one of the epic sieges of the Second World War.

During these frustrating days the Assam Regiment, which had been sent from Kohima to Jessami and Kharasom, was bearing the brunt of the attack by 138th Regiment, the leading unit of Sato’s 31st Division. The first action took place on 28 March at Jessami when the Assam Regiment held their fire and then wiped out the leading Japanese platoon. The Assams had been told to hold their position to the last man, and this they prepared to do. The Japanese, after their first reverse, put in one attack after another and suffered big losses. They then brought forward 124th Regiment together with artillery and mortars. Faced by such over-whelming numbers, the Assam Regiment held grimly on, through days and nights of fierce hand-to-hand fighting, and they kept firing until the barrels of their Bren guns were red hot. One Japanese attack separated a part of the battalion from the main body, but both groups still fought on. Eventually the battalion received an order from Colonel Richards to withdraw, which they did on 31 March. However, Captain Young, commanding the minor unit, sent off his men, but stayed at his post alone, hurling grenades at the enemy until he fell riddled with bullets. Once again, as at Sangshak, the bravery and determination of an isolated unit had caused a vital delay to Sato’s leading forces. From the Assam Regiment and the Assam Rifles about 250 survivors eventually reached Kohima by 3 April.

Sato and 31st Division had made good progress towards Kohima, and his HQ was now south of Jessami, but he was angry that the advance of his whole division had been held up by determined opposition. Later he complained, with considerable justification, that if his leading units had bypassed Sangshak and Jessami the outcome of the Kohima battle would have been very different.

While 161st Brigade was returning to Kohima, the advance guard of 2nd Division were arriving at Dimapur to scenes of complete chaos. They grumbled that they were arriving in a fighting zone in dribs and drabs and without weapons, guns or transport. The Dimapur stores were disposed over an area 11 miles long by 1 mile wide; most of the staff had fled and there was indescribable confusion. Again, the fighting units criticized the HQ staff. The return of the Royal West Kents to Kohima on 5 April could not have been more discouraging. They noticed that bunkers and trenches had been badly sited, no good gun positions had been established and even the garrison HQ had not been properly dug in. At least the trenches they had previously dug were still there, and they rapidly dispersed to their company positions on IGH Spur, Garrison Hill, Kuki Piquet and DIS.

Already the Japanese 58th Regiment, which was in good heart despite its heavy losses at Sangshak, had moved towards Aradura Spur and had driven off some Manipur State troops. Next, at 0400 hours on 6 April, a Japanese company entered the Naga village and rapidly took over the buildings. The defenders seemed unaware of this, and casually turned up at 0900 to draw their rations. They were quickly and quietly captured. By midday the Japanese had control of the village and had brought up their main body of troops. Sato now had three regiments – the equivalent of three British brigades – all ready to attack Kohima. Slim’s assumption that the enemy would only advance to Kohima with a couple of battalions proved to be dangerously inaccurate.

For their part the Royal West Kents were incensed at being separated from their brigade and their division, with whom they had trained, and had been thrown into a serious fight with, as they saw it, a lot of odds and ends of base units. Their criticism fell, unfairly, on the garrison commander, Colonel Richards, who had himself been pitchforked into a difficult situation. Brigadier Warren, of 161st Brigade, made matters worse by refusing to communicate with Richards and speaking only to Laverty, the CO of RWK. Later in the siege Laverty, carrying his prejudice to absurd lengths, even refused to re-charge the wireless batteries at Richards’ HQ, thus adding to already serious difficulties.

On 6 April Warren made an important decision. The remainder of his brigade, including 1/1st Punjabis, 4/7th Rajputs and 24th Indian Mountain Regiment, had reached Jotsoma, about 2 miles west of Kohima. He therefore established a defensive box at Jotsoma from which there was good observation of the whole of the Kohima ridge, and towards which there was a reasonably good track for the brigade transport. He quickly established the guns on a reverse slope and registered fire tasks on to likely targets on the Kohima battlefield. These guns, helped by the outstanding observation work of Major Yeo inside the garrison, achieved a high level of remarkably accurate fire which they kept up throughout the siege. On 6 April the Japanese put in their first major attack. They took Jail Hill, and though they sustained heavy losses they continued their advance and made another attack on DIS and FSD. The defenders were helped by the guns from Jotsoma, which put down pre-arranged fire tasks and caused heavy casualties among the Japanese attackers. They, in turn, replied with 75mm guns sited on GPT Ridge. The persistent Japanese attacks gradually made inroads into the Royal West Kents’ positions and began to threaten C and D Companies’ positions on FSD and DIS. By the morning of 8 April Royal West Kents were effectively dug-in, with most of the men in slit trenches. That morning the trenches lay cold and wet under a thick mist, a mist which chilled everyone and added to the fear and uncertainty. The men stood-to and checked the fixed lines for the Bren guns. Rather to their surprise, just after stand-to, the cooks arrived with tea, porridge, sausage, bacon and biscuits.

The forward platoon on DIS faced Jail Hill which had been held briefly by a scratch group of Gurkhas, but was now held by the Japanese who, from that vantage point, could overlook most of the RWK positions. Laverty considered a counter-attack, but realized that he had not enough men to carry it out. Instead, the 3-inch mortars under their outstanding NCO, Sergeant King, were cleverly resited and then retalliated effectively. The rest of the platoons continued with their digging, studied the ground ahead, improved their field of fire where possible and waited for the regular hail of shells and mortar bombs which the Japanese normally sent over at dusk. After the bombardment the Japanese tried their old trick of shouting `Hey! Quick, let me through, the Japs are after me!’ The RWK, having met this trick in the Arakan, held their fire so as not to reveal their positions to the accurate Japanese snipers. Usually, the Japanese attacked with screams and yells and with bugles blowing, but occasionally, they crept forward in total silence to within a few yards of the forward trench. That night the Japanese threw in one attack after another and gradually infiltrated the Royal West Kents positions on FSD.

This incursion threatened the other positions and had to be removed. Laverty quickly organized a counter-attack on FSD and the bashas now occupied by the Japanese. A young sapper officer invented an ingenious pole charge with gun-cotton in ammunition boxes, to destroy the walls of the bashas and help the infantry forward. This attack was to provide an example of truly remarkable heroism by Lance-Corporal Harman of the Royal West Kents, which inspired his own platoon and strengthened the whole battalion through the grim weeks ahead. As his platoon attacked they came under heavy automatic fire and a shower of grenades. Harman saw two machine-guns on the flank, walked calmly towards them, used his teeth to pull the pin from two 36 grenades, and lobbed them into the enemy weapon pit. He jumped into the pit and soon emerged holding up the machine-gun. Seeing this, the whole platoon charged forward and in hand-to-hand fighting cleared the enemy from the bashas. One larger building remained. Harman entered this and found that it had been the bakery, and the Japanese were hiding in the large ovens. He rushed out to fetch grenades and returned to the bakery. There were ten ovens and he dropped a grenade into each. Afterwards, finding two Japanese still alive, he picked them up and carried them back to his platoon lines, to a wild round of cheering.

The following morning, 8 April, after a night of shelling, jitter raids and company attacks by the Japanese, D Company RWK had to mount another counter-attack against a machine-gun post. Harman ordered his Bren gunner to give him covering fire and walked calmly forward, stopped twice to kill two Japanese defenders, fixed his bayonet and then charged the post. He finished off three men with his rifle and bayonet, and then jumped out of the trench holding up the machine-gun. Then, to the horror of his watching comrades, he began to walk casually back towards his lines. They yelled to him to run, but he kept walking and despite their covering fire was cut down by automatic weapons. His friends rushed out and carried him back to his trench, where he looked up and said, `I got the lot, it was worth it.’ He died a few moments later. He was subsequently awarded a posthumous VC.

Harman’s bravery saved a critical situation, but the Japanese continued their attacks as more reinforcements – including elephants carrying heavy guns – came up. On the same day, the Japanese 138th Regiment had circled to the north of Kohima, and had cut the Dimapur to Kohima road at Zubza (Milestone 36), thus cutting off Kohima garrison as well as 161st Brigade at Jotsoma.

At this stage of the siege, there is an interesting contrast in the conditions suffered or enjoyed by neighbouring units. While the whole of his brigade were cut off and faced a very grave military situation, Brigadier Warren, at Jotsoma, who had bought some chickens from a local village, had a chicken run built near the officers’ mess. He also got his water carriers to pick wild raspberries which he had for supper; after supper he usually played a few hands of pontoon with his brigade staff.