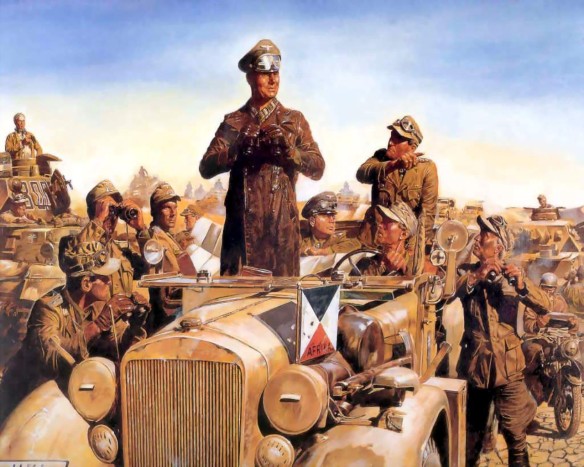

“Heia Safari – The Afrikakorps” by Nicolas Trudgian

Elements of the 10th Panzer Division, Army Group ‘Afrika’, counter-attack Allied forces in Northern Tunisia, early spring 1943. Overhead, air support is provided by the Ju87Ds of St.G3 and the formidable Fw190A fighters of II./JG2.

By comparison with the great battles waged across the Pacific, in northwest Europe, and on the Eastern Front, this campaigning between German and British Empire forces along the North African littoral was small in scale. But it was a superb test bed for the West’s innovators to try out newer ways of weakening German military power on land. For example, the two devices most commonly associated with Allied mine clearance efforts—the flail tank, one of the many contraptions in General Percy Hobart’s inventory of tricks, and the handheld acoustic mine detector, devised by the remarkable Pole Jozef Kosacki and given freely to the British Army, were both products of this particular battleground. To later armies across the globe, not having mine detectors in their armory would seem absurd, just as it would seem ridiculous to fight without advanced radar or decryption machines. Like many of the other novel Allied weapons examined in this book, this one also began as a small experiment. In his earlier life Kosacki was an engineer, and after the war he became a professor of technology and engineering. In 1942, however, he was a lieutenant and technical specialist in the British-Polish army, and eagerly desired to say thank you to Britain. It all fitted nicely together, and the mine detector arrived just in time to be used by Montgomery’s sappers when the Eighth Army at last took the offensive.

Given the massive reinforcements of tanks, trucks, artillery, and aircraft the Allies were now sending to the Middle East theater, El Alamein was probably Rommel’s (and Hitler’s) last chance to overcome the British-led forces, the last chance to seize Cairo and the Suez Canal, both hugely important strategically and symbolically. The pulling back of the Mediterranean Fleet farther east in September 1942 and the sight of confidential files being burned outside Middle East HQ in Cairo (shades of the Quai d’Orsay in May 1940) remind us that the British authorities regarded a German breakthrough as a possibility. But even if there was not a complete German victory, a heavy punch might be sufficiently destructive of Montgomery’s forces that Rommel could control the El Alamein–Quattara Depression gap and make it impassable for ages to come. This fight was also Montgomery’s (and Churchill’s) best opportunity to demonstrate that British Commonwealth forces could beat German panzers and infantry in the field, not defensively as at Alam Halfa but continuously, pushing them back again and again, harassing and sweeping aside attempted blocking points, taking ever more prisoners, and driving the Germans and Italians toward Eisenhower’s armies at the other end of the North African shores.

For once, the terrain around El Alamein favored the cautious British armies. Indeed, looking at the story of the land wars between 1940 and mid-1942, a military analyst might argue that this topographic setup was the only one in which British Commonwealth armies had much of a chance of defeating their more experienced German counterparts. The other major card in Montgomery’s hand was sheer superiority in numbers—and not just in frontline forces but in fuel and other supplies as well, and in near-total command of the air. By this stage, the Luftwaffe’s strength was much reduced, while British and American tactical aircraft squadrons were pouring into Egyptian bases. The ninety-six squadrons available to the air C in C Sir Arthur Tedder (around 1,500 aircraft) across the Middle East not only represented a much larger and more modern air fleet than the mere 350 Italian and German planes that opposed them, but now packed a far bigger punch as well. Medium-range bombers based around Cairo joined Malta-based aircraft in vastly reducing Axis supplies across the Mediterranean; the Royal Navy’s famous U-class submarines (also based out of the great caves in Malta’s harbors) wrought havoc, too. The Italian merchant ships that got past these blockades were then terribly vulnerable to low-altitude attack as they unloaded in harbor. Axis supply lines along the narrow coastal road were frequently attacked—trucks and staff cars being the favorite target—while Rommel himself displayed an amazing lack of interest in military logistics and supply limitations.

Because of improved shortwave radio communications, Eighth Army units at the front could now call in fighter-bomber squadrons for direct attacks upon enemy panzers, motorized divisions, and troop clusters. If aircraft losses to ground fire were high, replacements were always arriving. Most important of all, RAF tactical airpower, so miserable or nonexistent in the first three years of the war, was coming of age. Air Vice Marshal G. G. Dawson was transforming the air force’s hitherto lamentable record in repair and maintenance; above all, the coordinated tactical air doctrines developed by the Western Desert Air Force under Air Marshal Arthur Coningham—that is, with a central command linked by radar and radio both to army headquarters and to the attacking squadrons—proved so obviously effective that it became standard practice for both the Sicily and Normandy operations later.

Under this aerial umbrella, knowing that further reinforcements were flowing up the Suez Canal each week, and having resisted Churchill’s demands for action until he was fully ready, Montgomery unleashed a barrage of a thousand-plus guns on October 23, 1942. If, as most experts would concede, artillery was the queen of the battlefield during the slug-it-out fights that characterized the second half of the Second World War, then the Allies’ advantage in numbers and firepower was about as great as their aerial superiority (specifically, 2,300 British artillery pieces against 1,350 Axis artillery, of which 850 were very feeble Italian guns). Moreover, the Eighth Army’s gunner regiments were at last concentrated in strong groupings rather than being scattered up and down the front. Montgomery’s reinforced and varied army (British, Australian, New Zealand, South African, Indian, Polish, and Free French divisions or brigades) could deploy three times more soldiers than Rommel’s combined Italian and German troops, and his tank force of more than 1,200 vehicles, including 500 of the more powerful Shermans and Grants, far eclipsed the German-Italian armored regiments in firepower, range, and armor. But the depth of the German minefields slowed things down greatly, and the Eighth Army’s painstaking drive to clear them gave Rommel good clues as to where to position his relatively few but terrifyingly effective 88 mm antitank platoons.

This time the sheer weight of Montgomery’s pressure meant that the Axis lines just buckled under the relentless pressure; more and more British tanks were knocked out by German mines, bazookas, and the 88 mms, losing at a rate of four to one, but they still kept coming, and they could sustain their losses more easily. The Italian tanks were blown away, the lighter German tanks swiftly destroyed, the artillery barrage continued, the daytime air strikes intensified. By the end of the epic battles of November 2, during which the British had seen almost two hundred of their tanks lost or disabled, they still had another six hundred in hand; Rommel had thirty. Then the German retreat began, often leaving large numbers of less mobile Italian forces behind. The discipline of the Afrika Korps over the next few days in deploying alert and hard-fighting rear guards while the bulk of their transport units filtered through cannot but command admiration, but the blunt fact was that the Germans had lost in the most decisive battle for North Africa.

During the night of November 7, as Rommel used the drenching rains to cover his westward withdrawal from the coastal position of Mersa Matruh, massive Allied invasion forces were arriving off the Moroccan and Algerian coasts to implement Operation Torch. In that larger sense, the German-Italian forces in North Africa were now caught in a gigantic pincer movement, with Eisenhower’s forces pushing the defenders to the east and Montgomery’s divisions chasing them back to the west until they ended up, surrounded, in Tunisia in early 1943. This was how the German blitzkrieg ended, at least in the Mediterranean theater.

Yet the Wehrmacht still fought on. Part of the reason the British Eighth Army only gingerly followed up—rather than earnestly pursued—the retreat of the Afrika Korps along that very familiar Sidi Barrani–Tobruk–Benghazi route was that Rommel’s diminished cohorts would suddenly turn and bite, or would set up prepared positions from which they would give the Commonwealth forces a good drubbing. Then Rommel would retreat a bit more, just as Allied commanders were bringing forward massive aerial and armored forces to assault a force that was no longer there. Perhaps the British and American commanders (or most of them) accorded the Germans too much respect, but the record shows that there was good reason to do so.

The Germans perhaps might have significantly delayed what was later termed the “clearance of Africa” if Hitler had earlier given Rommel the divisions he belatedly ordered into Tunisia on learning of the Torch landings, or if Rommel had been freed from the complications of being formally under Italian command and from the rivalry of his coequal General Hans-Juergen von Arnim in the final months. To be sure, the massive Allied air, land, and sea superiority really made the outcome in North Africa all but inevitable, but if a German defeat had been much later, there could have been serious knock-on effects for the planned invasions of Sicily and Italy, and possibly a revival of Anglo-American disagreements about when to launch the second front in France. The Fuehrer’s erratic interventions (tolerating the Arnim-Rommel rivalry, trickling in reinforcements, sending units to guard against an Allied invasion of Greece) were by now giving the Allies unexpected benefits.

As the Western Allies moved into southern Europe, the German military record on the ground would remain impressive. The German command chose not to contest the massive Allied landings in southern Sicily, but then held on in the northeastern mountains of that island against repeated assaults by Patton’s forces. When the time was ready to go, they smartly slipped away across the Straits of Messina, but they also chose not to stand in the vulnerable “toe” of Italy, where they might be outflanked; instead, they withdrew farther north, the better to resist. And the able Kesselring (after persuading a dubious Hitler that such a strategy was feasible) was preparing successive lines of defense between the Mediterranean and Adriatic coastline and running all the way up that lengthy, rocky, difficult Italian peninsula. When the Anglo-American armies tried to foreshorten this campaign by landing behind the front, the German response (Salerno, Anzio) was ferocious. All such counteroffensives by the Wehrmacht could be contained only by an overwhelming abundance of Allied force: total control of the air, the massive use of battleship and cruiser bombardments, and the bringing in of more and more army divisions. More Allied casualties were suffered in the battles in Italy than in any other campaign in the West.

Hindered by meager supply lines, poor intelligence, loss of aerial support, and the constant damage inflicted by Hitler’s obsessions and interventions, the Wehrmacht’s divisions on the Italian and, later, northwest European fronts showed great resilience right up to the end of the war. The tenacity and operational effectiveness of a seasoned German army regiment or division had no equal in the Second World War. Only superior numbers could beat them. Some years ago the American military expert Trevor Dupuy attempted a systematic analysis of all the main battlefield encounters between German, British, and U.S. army units during the North African, Italian, and northwest Europe campaigns. Division for division, and without much exception, the German units overall had a 20 to 30 percent combat superiority (though even that may be too generous toward the Western armies).

Yet a “superior numbers” argument is not enough. By the end of 1943 the British were introducing into the North African struggle a remarkable number of force improvements: superior radar, superior decryption, a much better orchestration of tactical airpower, much better coordination between the army and the RAF, unorthodox Special Forces units (the Germans and Italians had none), aircraft that were more powerful and more adaptable, the mine-flaying tanks and the acoustic mine detectors, and, sitting above this all, a far better integrated command-and-control system than at the time of the Crete and Tobruk disasters. They had worked it out at last, and Montgomery—and his publicity team—were the beneficiaries of much hard work and deep thought. Even before the epic struggle in the wastelands of Russia, it seemed the German blitzkrieg could possibly be defeated by superior numbers, positioned in depth; but those numbers also needed more advanced weaponry and a superior organization. It had taken the British Army and RAF a long time, and Churchill’s relief was enormous.