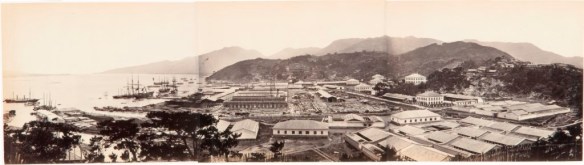

The Foochow Arsenal under construction, between 1867 and 1871. Three albumen prints joined to form a panorama.

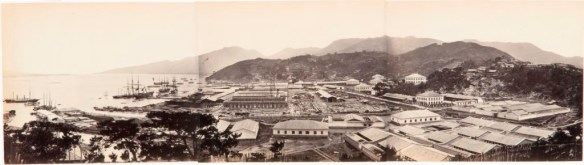

The Chinese flagship Yangwu and the corvette Fuxing under attack by French torpedo boats No. 46 and No. 45. Combat naval de Fou-Tchéou (‘The naval battle at Foochow’), by Charles Kuwasseg, 1885

The naval battle off Ma Wei, a small town at the mouth of the Min River on the east bank opposite the city of Fuzhou, was the opening of hostilities in the Franco-Chinese War. At the time of the battle, China had more than 50 ships in its navy, including German- and American-built gunboats and cruisers. About half of the ships were constructed in China, some at the Fuzhou Dockyard, near where the battle was fought. However, China had not organized its ships into a national fleet. Instead, they were controlled by regional governors-general appointed by the Qing dynasty.

The governor-general of Canton (Guangzhou) had constructed a series of fortifications along the Fujian Province coast, including along the Min River. The Fuzhou Dockyard superintendent was He Ruzhang, who had overall responsibility for the Fuzhou fleet. However, the tactical control of the fleet’s ships was the responsibility of Zhang Cheng, the captain of the fleet’s flagship, the Yang Wu.

The French fleet in Asia was dispersed off the South China and Indochina coast under the control of Admiral Amende A. P. Courbet. Although no formal state of war was declared, there were serious disputes between the French and the Chinese over control of the northern part of Vietnam (Cochin China) and the surrounding waters. The French fleet in the area in July 1884 was led by Courbet’s flagship, the Volga, and consisted of four other warships. By August 22, 1884, the French naval presence off the Min River had grown to eight warships, all anchored in the approaches to Fuzhou in the Ma Wei roads. The ships all had armor-clad hulls and were considered modern for the time. The Chinese had a fleet of 11 wood-hulled ships with modern armament at Fuzhou. In addition there were seven steam-driven launches and 12 armed junks used for troop transport. After a dispute over unimpeded access to the river for the purpose of trade, which had gone on since early July, the French initiated action against the Chinese fleet on the afternoon of August 23, 1884.

There are different accounts of whether there was any declaration of war on the part of the French before hostilities commenced. As a minimum, it seems likely that some Chinese official, if not the governor-general in Canton himself, was notified that the French would attack if a blockade of the Min River by the Chinese was not lifted. Perhaps an official of the Fuzhou Dockyard was given an ultimatum by Courbet. In any case, within about 12 minutes of the commencement of action by the French at about 2:00 P. M. on August 23, they had sunk almost the entire Chinese fleet. Varying accounts of the battle say that all 11 Chinese warships were sunk; others say that as many as 22 Chinese ships of different classes were sunk. Only five Chinese ships were reported to have gotten under way from the Fuzhou Dockyard, and only two of these escaped upriver unscathed. Command and control signals for the Chinese fleet were poor, whereas only two French ships suffered minor damage from fire.

China declared war on France on August 26, 1884.

FUZHOU DOCKYARD

The Fuzhou Dockyard was one of several regional weapons arsenals and shipyard facilities established in China by local officials with foreign equipment or assistance. Other arsenals and dockyards were established in Shanghai (Jiangnan), Suzhou, Nanjing, Tianjin, and Jilin. The Fuzhou Dockyard was established primarily with French assistance after two Frenchmen who had helped raise armies during the Taiping Rebellion, Prosper Giquel and Paul D’Aiguebelle, signed a contract with Zuo Zongtang to operate the dockyard. The contract was signed in 1866, and the dockyard was actually established under contract to build 16 ships in 1867.

In fact, the contract with Zuo Zongtang called for more than ship construction. Giquel and D’Aiguebelle were also supposed to establish a naval engineering school and a navigation school at Fuzhou, all within a five-year period. The dockyard was to be operated by Chinese natives after the expiration of the contract. The Fuzhou Dockyard launched its first ship June 1869, the Wan Nian Qing (Ten Thousand-Year Qing Dynasty), a steam-powered, 238-foot ship with six guns, powered by a screw propeller rather than paddle wheels. By 1873, 11 warships of various classes, from corvette to gunboat, had been produced by the dockyard. The final four ships constructed at the Fuzhou Dockyard were merchant ships built to haul passengers and cargo. Three of these, the Chen Hang, Yong Bao, and Da Yu, carried troops from Li Hongzhang’s Anhui Army to Taiwan during the Formosa Crisis of 1874 with Japan.

Between 1874 and the Franco-Chinese War (1884-1885), the Fuzhou Dockyard launched an additional seven ships, which were of composite, iron frame wooden skin construction. But the dockyard was continually hampered by financial problems and, in fact, supported partially by opium taxes. After the Franco-Chinese War, the dockyard’s financial situation improved, but it had to begin procurement from sources other than France, turning primarily to England and Germany.

REFERENCES John L. Rawlinson, China’s Struggle for Naval Development, 1839-1895 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967); Bruce Swanson, Eighth Voyage of the Dragon-A History of China’s Quest for Seapower (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1982). Li Hong Chang, Memories of Li Hong Chang, ed. William Mannix (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913); Prosper Giquel, The Foochow Arsenal and Its Results: From Commencement in 1867 to the End of the Foreign Directorate on 16 February, 1874, trans. H. Lang (Shanghai: 1874); John L. Rawlinson, China’s Struggle for Naval Development, 1839-1895 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967).