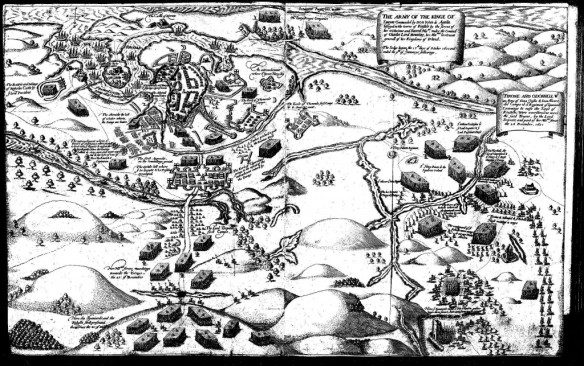

The Siege and Battle of Kinsale, 1601. The Lord Deputy’s Camp is in the centre left of the image (Pacata Hibernia, 1633)

PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Ireland and Spain vs. England

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Ireland

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Disliking English taxes, English religion, and English rule, the Irish took advantage of the outbreak of war between Spain and England to stage a revolt.

OUTCOME: Following some initial success, the Irish rebellion was crushed; its leader, however, was pardoned and went into exile.

APPROXIMATE MAXIMUM NUMBER OF MEN UNDER ARMS: England, 18,300; Ireland, 10,000

CASUALTIES: At Yellow Ford, English, 1,500 killed or missing; at Curlieu Hills, 240 killed, 208 wounded; at Kinsale, 20 killed. Total Irish and Spanish losses at Kinsale, 1,200 killed; other totals, unknown.

In the 16th century, England’s overseas commerce had begun to grow. The expansive and adventuresome spirit that had led the English “sea dogs” around the world now gained support from the birth of a Royal Navy. Old insular Britain was changing, and its obvious enemy was Spain, the nation then dominating the oceans and monopolizing the most lucrative colonial trade, especially that of the New World. Efforts to avoid the rivalry, such as the marriage of Mary I (1516-58) to Philip II (1527-98) of Spain had proved useless, and Elizabeth I (1533-1603) had been engaged in a decade of undeclared war with the Iberians- on the high seas, in America, and with the Netherlands- when the formal hostilities broke out that ultimately led to the arrival of the Spanish Armada. The conflict was greatly intensified by its religious dimension. Spain was Catholic, England Protestant, and this difference provoked rebellion in the British Isles.

The Irish, chronically maltreated by the English, sharply resented the taxes Elizabeth I levied to maintain England’s new presence in the world. Moreover, as Catholics, they hated her Protestant ecclesiastical policies. Thus, the Irish were inclined toward Catholic Spain, and in 1594, Hugh O’Neill (c. 1540-1616), second earl of Tyrone, joined the already rebellious “Red” Hugh O’Donnell (c. 1572-1602) to unite the Celtic dissenters.

The most significant military action in 1594 came on August 7, when an English force of 600 foot and 46 cavalry, escorting a large supply train, was ambushed by 1,000 Irish infantry and 100 horsemen. Fifty-six English were killed and 69 wounded. The rest fled the field, abandoning the supply train. The exchange was dubbed the “Battle of the Biscuits,” because the English left a multitude of biscuits and cakes behind as they fled. O’Neill appealed to Spain for assistance as rebellion in Eire erupted into full-scale war with the English by 1595. O’Neill raised an army of 10,000 and defeated the English at Yellow Ford on the Blackwater River on August 14, 1598, the climax of a series of brief encounters during which O’Neill had bested the queen’s top commanders.

In 1599, Elizabeth sent her favorite, Robert Devereaux (1567-1601), the earl of Essex, with 17,000 infantry and 1,300 cavalry, to crush the Irish rebels, but Tyrone’s troops outmaneuvered him for more than a year, as they waited for Spain to respond to the call for aid. In 1600, Essex- after suffering a number of reverses-gave up and concluded a peace with the Irish forbidden to him by his queen. Elizabeth angrily recalled Essex, just in time for 3,814 Spanish soldiers under Don Juan D’Aquila (fl. 16th century) to arrive in Kinsale, Ireland, in 1601. The Spaniards took Kinsale, but the English-11,800 foot and 857 horse-led by Charles Blount (c. 1562-1606), Lord Mountjoy, kept D’Aquila’s troops from uniting with Tyrone’s men and laid siege to Kinsale on November 21, 1601. Disease and combat casualties reduced Mountjoy’s force to 6,595 men fit for duty. Tyrone arrived with 6,500 Irish rebels, but the English responded with a vigorous cavalry charge executed during a severe thunderstorm on December 24. The combination of English ferocity and the fury of the storm apparently instilled panic in the Irish troops. A line of 1,800 pikemen broke and ran, prompting the Spaniards to retreat as well. Twelve hundred Irish and Spanish soldiers fell in this battle, whereas the English lost perhaps 20 men. On January 2, 1602, Aquila surrendered, and by 1603 O’Neill laid down arms and Tyrone surrendered as well. Both leaders were subsequently pardoned by King James I (1566-1625) and prudently went into voluntary exile. By 1603, the English had fully suppressed the uprising.

Further reading: Colm Lennon, Sixteenth-Century Ireland: The Incomplete Conquest (New York: St. Martin’s, 1995); Hiram Morgan, Tyrone’s Rebellion: The Outbreak of the Nine Years’ War in Tudor Ireland (London: Boydell and Brewer, 1999).