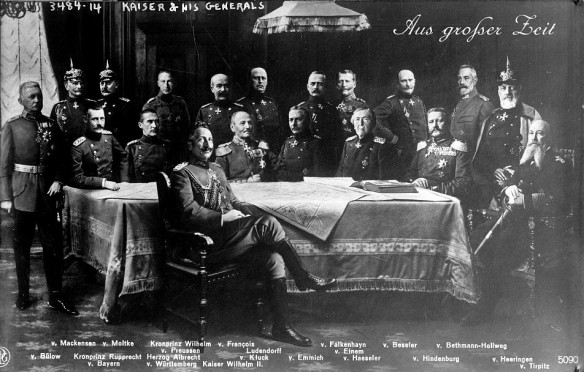

William II with his generals.

Erich von Ludendorff.

(April 9, 1865–December 20, 1937) German Staff Officer

Brilliant but mercurial, Ludendorff possessed one of the best tactical minds of World War I. When coupled with the steadying influence of Paul von Hindenburg, they constituted a formidable offensive team. However, Ludendorff proved stubborn and shortsighted in a strategic sense, and his policies actually hastened Germany’s defeat in World War I.

Erich von Ludendorff was born in Kruszevnia, East Prussia (modern-day Poland), on April 9, 1865, the son of middle-class parents. Despite these nondescript origins, he decided upon a military career and became a cadet in 1877 at the age of 12. Prospects for men of nonaristocratic birth were usually limited, but Ludendorff proved himself exceptionally adept as an officer. Rising through merit, he breezed through the Kriegsakademie (war college) in 1893 and two years later joined the prestigious General Staff as a captain. In this capacity he ultimately headed the mobilization and deployment section of that body. But having arrived at such a high station, Ludendorff began exhibiting two qualities that characterized his later military career: intense brilliance and abrasive impetuosity. In 1913, he drafted extensive plans for expanding manpower and munitions, an excellent scheme that was rejected by the war ministry as too risky. Moreover, when he clandestinely and illegally lobbied several politicians to support his plan, Ludendorff was dismissed and assigned to an infantry regiment far from Berlin. The following year he rose to brigadier general at Strasbourg just prior to the commencement of World War I.

In August 1914, Ludendorff functioned as deputy chief of staff to Gen. Karl von Bulow’s Second Army and accompanied the advance into Belgium. There he distinguished himself in the capture of several strategic forts, winning the prestigious Pour le Merite, Germany’s highest honor. At this time, large Russian armies were poised to overrun East Prussia, then weakly garrisoned, and Gen. Max von Prittwitz ordered a hasty withdrawal. To counter this, Ludendorff was teamed with a little-known officer named Paul von Hindenburg as the latter’s chief of staff and sent east. From the onset, the two men formed one of the greatest fighting duos of military history, with Hindenburg’s gravity and prudence counterbalanced by Ludendorff’s impetuous brilliance. In short order, the two men turned around the German Eighth Army, attacking and routing the Russians at Tannenburg and Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914. Throughout the fall and well into winter, Ludendorff continued hammering away at huge Russian armies, capturing thousands of prisoners and pushing the enemy back. Consequently, like Hindenburg, he acquired national acclaim and accorded near-mythic qualities. Both men, furthermore, felt that the time was right for a massive blow to knock Russia out of the war. This was strategically imperative, for Germany was severely disadvantaged fighting along two fronts. But German planning became ensnared by conflicting strategic priorities. The current chief of staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, sought a decisive victory in the West by taking troops from the Russian front and pouring them into a bloody battle of attrition at Verdun. Hindenburg and Ludendorff strongly protested these transfers, but even with smaller forces they nearly drove Russian forces out of Poland in 1916. When Falkenhayn’s strategy failed at Verdun, he was replaced by Hindenburg. The egotistical Ludendorff, who did not wish to be referred to as a mere deputy chief of staff, was also granted the title of first quartermaster general of armies. The conduct of German armies for the remainder of World War I was now in their hands-and they resolved to win at any cost.

Although the junior partner in this dynamic duo, Ludendorff was by far the most influential and aggressive. In the spring of 1917 he planned the successful Caporetto offensive for Austria, which nearly knocked Italy out of the war. His directions then led to the collapse and acquisition of Romania. Meanwhile, the nominally detached Hindenburg contentedly functioned as a figurehead, allowing Ludendorff to implement wide-ranging military and economic policies in his superior’s name. A failure of nerve on the part of Kaiser Wilhelm II, who feared and detested Ludendorff, coupled with the reluctance of politicians to question his motives, meant he was literally a military dictator. As such he oversaw the introduction of forced Belgian labor, increases in military expenditures, and conscription to shore Germany’s flagging army. He also arrogantly dismissed the thought of a negotiated peace settlement as national weakness. But most important, Hindenburg and Ludendorff felt that a six-month naval blockade by Uboats would bring England to its knees. Therefore, over the objections of Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, who was sacked at Ludendorff’s instigation, Germany reenacted the policy of unlimited submarine warfare at sea. Henceforth, the ships of neutral carriers such as the United States were liable to attack if they traded with England. Like his superior, Ludendorff realized this policy would eventually result in America’s declaration of war against Germany, but they felt time was on their side. In October 1917, horrendous Russian losses prompted the Bolshevik Revolution, which forced the giant in the east to sue for peace. This act released thousands of German soldiers for service along the Western Front, where they were needed as reinforcements. Both Hindenburg and Ludendorff optimistically predicted that Germany could crush France and England before the United States mobilized its military resources and manpower against the Fatherland. It was a high-stakes strategic gamble, but one for which Germany-thanks to Ludendorff-was well-prepared.

Through the fall of 1917, Ludendorff oversaw the development of new infantry tactics intent upon breaking the strategic stalemate. This entailed training German troops in the new “storm trooper” tactics, whereby small bodies of highly trained specialists, backed by artillery, would infiltrate along enemy-held strong points and attack rear areas. This was a complete departure from the mass bombardment and mass infantry attacks that had characterized fighting since 1914. This established Ludendorff as a brilliant tactical innovator, whose ideas anticipated what became standard practice in World War II 20 years later. In March 1918, the new German offensive sprang at the Allies along a 50-mile front with resounding success, sending trench-bound French and English forces reeling in confusion. After a series of interrelated offensives, German armies were once again poised to cross the Marne River in June 1918. Ludendorff’s gamble thus far appeared successful, but it carried a fearsome price: 500,000 men had been killed and wounded.

Unfortunately for Germany, Ludendorff’s faith in the offensive blinded him to the fact that Germany’s manpower resources were exhausted and could no longer sustain such attrition. Furthermore, to Ludendorff’s complete surprise, the first American contingents had already arrived in France and fought the last German advance to a standstill at Chateau-Thierry on May 30, 1918. Over the next two months the Allies, battered by Ludendorff’s offensive but never broken, steadily pressed back their tormentors. Ludendorff, who never had much regard for tanks, received an abject lesson in armored warfare when a tank-led British assault upon Amiens produced 30,000 prisoners-he subsequently pronounced it the “black day of the German army.” Worse, as greater and greater numbers of American troops were marshaled under the inspired leadership of Gen. John J. Pershing, they conducted several capable offensives on their own at St. Mihiel and Meuse- Argonne. By October, it was clear that the war was lost; Ludendorff advised the Kaiser to make peace and abdicate. He then backtracked and unrealistically urged Germans to fight to the finish, at which point Prince Max von Baden, head of the provisional government, demanded his resignation.

After the war, Ludendorff fled to Sweden, where he composed his memoirs. He returned to the shattered, postwar Germany to partake of the growing right-wing political movements springing up, and he also dabbled in various Nordic religions. Having embraced extreme racial and national ideology, the former general participated in Adolf Hitler’s ill-fated Kapp Putsch in Berlin and was arrested. Memory of his previous wartime service spared Ludendorff from imprisonment, and in May 1924 he gained election to the Reichstag (parliament) as head of the new National Socialist (Nazi) deputation. The following year Ludendorff humiliated himself by running as the National Socialist candidate for the presidency, winning a scant 1 percent of the popular vote. He then broke with Hitler, accusing him of cowardice and incompetence, and continued his personal war against Jews, Jesuits, and Freemasons. Ludendorff died in Tutzing, Bavaria, on December 20, 1937. His bizarre embrace of radical politics notwithstanding, he was one of the master spirits of World War I, a capable strategist and a brilliant tactician. Had Russia been knocked out of the war in 1916 as he envisioned, Germany might have decisively prevailed in that conflict.

Bibliography Arnold, Bradley C. “Snatching Defeat from the Jaws of Victory: General Erich Ludendorff and Germany in the Last Year of World War I.” Unpublished master’s thesis, James Madison University, 2000; Asprey, Robert B. German High Command at War: Hindenburg and Ludendorff Conduct World War I. New York: William Morrow, 1991; Buckelew, John D. “Erich Ludendorff and the German War Effort, 1916-1918: A Study in the Military Exercise of Power.” Unpublished master’s thesis, University of California, San Diego, 1974; Drury, Ian. Storm Trooper. Oxford: Osprey, 2000; Dupuy, Trevor N. The Military Lives of Hindenburg and Ludendorff. New York: Watts, 1970; Fleming, Thomas. “Day of the Storm Trooper.” Military History 9, no. 3 (1992): 34-41; Greenwood, Paul. The Second Battle of the Marne. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publications, 1998; Kitchen, Martin. The Silent Dictatorship: The Politics of the German High Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff, 1916-1918. New York: Holmes and Meier, 1976; Ludendorff, Erich. Ludendorff’s Own Story, August 1917-November 1918. New York: Harper and Bros, 1919; Parkinson, Roger. Tormented Warrior: Ludendorff and the Supreme Command. New York: Stein and Day, 1979; Samuels, Martin. Doctrine and Dogma: German and British Infantry Tactics in the First World War. New York: Greenwood Press, 1992.