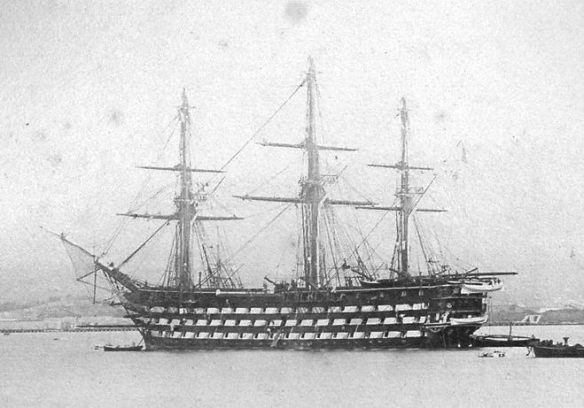

Ville de Paris in 1854. The escadre d’évolution, under vice-admiral Penaud. The ships Ville de Paris, Algésiras and Gloire can be seen.

Capture of Saigon by France, 18th February 1859.

When the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, Britain was the only global maritime power. Even with a major reduction in her navy, Britain’s naval power was unchallenged. From 152 battleships and 183 frigates in 1810, the navy shrank to 112 and 101 of each type by 1820. Still, her proportion of total world naval tonnage remained overwhelming and qualitative improvements increased the margins over potential rivals. Britain was determined to maintain a two-power standard. Political turmoil and the fragile economic recovery made renewed naval competition unattractive to most European powers. Only Turkey and Spain had maritime interests that were directly threatened between 1815 and 1830. Spain was faced by British determination to protect the independence movements and found it impossible to rebuild her navy, let alone challenge Britain. The Greek Revolt (1821–8) posed a direct threat to the maritime communications of the Ottoman Empire. The Turks responded by building up their fleet which resulted in the last major battle between sailing battlefleets.

The only other naval power whose capability showed a marked increase in the years following 1815 was the United States. Here the “navalists” had, temporarily, won the argument. Professional naval officers at last achieved a permanent influence on government policy with the creation of the Board of Commissioners in 1815. The importance of the navy to the state was emphasized by the growing Federal control over the appointment of officers. The officer corps had become established as part of the machinery of the state. The Navy Act of 1816 allowed for a fleet of nine battleships and 12 frigates, supported by a revenue bill which would ensure continued funding for maintenance. America finally had battleships, but soon found that in the postwar world the need was for the large frigates and other smaller vessels to combat piracy and, after 1818, slavers. In the years that followed, this disjunction between the battleship and American naval needs mixed with growing economic difficulties and new trading priorities in the Pacific revived “anti-navalist” feeling and in 1827 the battleships and the frigates were laid up. The United States found that its maritime ambitions were in line with British expectations and protected by them. It was not until the mid-1830s that American political attention again turned to creating a significant navy.

The European revival in naval building did not really accelerate until the 1840s. No state had a great interest in forcing maritime competition. Britain was satisfied with her position and did not want to become embroiled in conflict. After the successful bombardment of Algiers in 1816, the general situation in the Mediterranean suited Britain. Britain preferred a joint approach to maritime problems and discouraged unilateral naval action by France and Russia against the Barbary Corsairs and Greek pirates. During the early 1820s the Turks rebuilt their fleet in the wake of the Greek Revolt. Particularly active was the viceroy of Egypt, Mehmet Ali, who bought new ships from France and America and hired European officers to navigate them. Britain, France and Russia determined to use some naval forces to enforce a truce. This meant intercepting Mehmet Ali’s expeditionary force of 4,000 troops, which left Alexandria on 5 August 1827. The Anglo-French force, under Vice Admiral Sir Edward Codrington, met the Ottoman fleet anchored in line in Navarino Bay on 10 September. A prolonged truce followed and the Russians joined the allies on 11 October. On 18 October the allies decided that the Turks must be forced to conclude the negotiations before the winter and entered Navarino Bay. The forces were not large: 11 allied battleships and 16 other ships faced seven Turkish battleships and 58 smaller ships. The fierce artillery duel at short range and in the confines of the bay led to the loss of a Turkish battleship, 34 frigates and corvettes, and the best of the Turkish officer corps. The Turks were now unable to move their troops by water, but continued to fight on until November 1828 when a French land force finally took their last stronghold on the Morea. The Russian Black Sea fleet supported the army’s advance against Turkish positions at Varna on the Danube. Blockades of Turkish-held positions in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean and at Constantinople were established. British and French naval power was used to prevent the Russian conquest of Constantinople and encourage an armistice.

Sailing warships continued to be used all over the globe until the 1860s, but apart from a short blockade of the Dutch coast by French and British ships in 1830, the sailing wooden battlefleet was disappearing from European warfare. When the French and British fleets deployed in the Baltic in 1855, they were a mixed force of steam and sail. However, the sailing warship did not stagnate in its final years. In the first 40 years of the century, it reached the limits of contemporary design. Practical experience, particularly in combat with the American frigates, experimentation, such as that of Sir Robert Sepping’s work with rounded sterns, and, eventually, theoretical contributions, all combined to integrate the work of the shipwright and the emerging profession of naval architect. Britain, the leading maritime and naval power, now undoubtedly led the world in ship design and construction. The ships built in this period lasted for decades, but within 15 years of Waterloo, steamships were accompanying naval expeditions and by the 1850s the dominance of the sailing warship had entered its terminal stages.

British admiral. Born on 10 August 1753, at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, the second son of the fourth Earl of Berkeley, George Cranfield Berkeley was a member of one of England’s oldest aristocratic families. He attended Eton during 1761–1766, after which he entered the Royal Navy as a midshipman. Promoted to lieutenant in 1772 and to commander in 1778 when he took command of a sloop, his advancement in the navy was delayed because of his Whig political connections.

In 1780 Berkeley was appointed to a frigate as a post captain. He went on half pay in 1783 with the end of the War of American Independence, during which he had served in the Newfoundland Squadron and in the Channel and Mediterranean Fleets, and had fought at Ushant in 1778 and at Gibraltar in 1781.

Elected to Parliament from Gloucestershire in 1783, Berkeley was regularly reelected until 1810. His parliamentary career was not distinguished, however. A strong supporter of William Pitt’s government, he was named surveyor-general of the ordnance in 1789. At the outbreak of the French Revolutionary War in 1793, he took command of the Marlborough, a 74-gun ship in the Channel Fleet. He was severely wounded in the head in the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. Although he received with other officers the thanks of Parliament and one of the gold medals awarded, he was later accused of being a “shycock” in battle who “skulked in the cockpit.” He brought suit for this libel and won a favorable verdict.

On recovery from his injury, Berkeley in 1798 received command of the Sea Fencibles, the maritime militia along the Sussex coast. In 1799 he was promoted to rear admiral, and for the next two years he commanded a squadron in the Channel Fleet, first under Lord Bridport and then under Lord St. Vincent, who was critical of his performance. While St. Vincent was first lord of the Admiralty, Berkeley received no appointment, but in 1804, with the return of Pitt to office, he was made head of the Sea Fencibles for all of England.

Promoted to vice admiral in 1805, he was finally given an independent command in 1806 by the Grenville-Fox government when he became commander in chief of the North American Squadron. Because of his volatile temperament, his friends in the government were apprehensive about his suitability for an assignment that involved sensitive relations with the United States.

In the United States Berkeley soon became exasperated with the desertion of British seamen while his squadron was woefully undermanned. In June 1807 he issued the fateful order to stop and search any armed vessel suspected of having British seamen aboard. This led to the HMS Leopard’s firing on the American frigate Chesapeake off the Virginia Capes, the killing of three American seamen, the wounding of 18 others, and the removal of four seamen claimed to be British subjects. While Berkeley’s action in the circumstances may have been justified, war with the United States became a distinct possibility and the British government prudently disavowed the act and recalled him. Because of his influential connections, no further action was taken against him, and in late 1808 he was appointed commander in chief of the Lisbon Squadron, a post he held for three years.

Berkeley and the Duke of Wellington were closely associated during the Peninsular War. In 1810 Berkeley was made a full admiral, and that same year Portugal designated him Lord High Admiral in appreciation of his services. Berkeley’s active naval service ended with his retirement from the Lisbon command in 1812. Disappointed that he did not receive a peerage for his service, he was made a Knight of the Bath in 1813. Berkeley died in London on 25 February 1818.

References

Fisher, D. R. “Hon. George Cranfield Berkeley.” In The History of Parliament, the House of Commons, 1790–1820, ed. R. G. Thome, 5 vols., 3: 191–193. London: Secker & Warburg, 1986.

Gentleman’s Magazine 58, 1 (April 1818): 370–371.

Howard, David D. “Admiral Berkeley and the Duke of Wellington: The Winning Combination in the Peninsula.” In New Interpretations in Naval History, ed. William B. Cogar, 105–120. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989.

Naval Chronicle 12 (July–December 1804): 89–113.

Tucker, Spencer C., and Frank T. Reuter. Injured Honor: The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, June 22, 1807. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996.