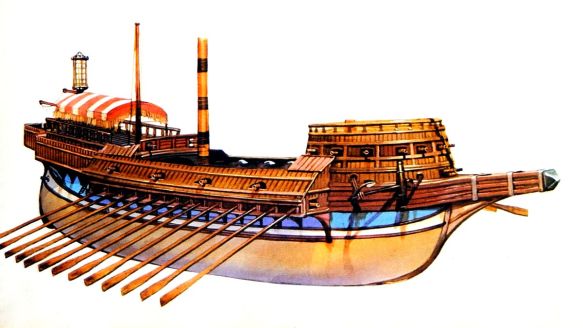

A floating fortress, the galleass was the ultimate and unwieldy result of an effort to combine both oars and broadside, taxing human muscle to the limit. Heavy cannon and high bulwarks made them dangerous attackers – and also impossible targets, for if they could not run down an enemy, they had little need to run away from one.

Battle of Lepanto.

If the siphon itself had perished with the fall of Byzantine Empire in 1453, other incendiary weapons had not. Both sides had men trained to throw clay pots filled with flaming oil, animal fat or quick lime to set the enemy decks ablaze or render them perilously slippery. Arms and cannon threw hollow iron balls filled with burning matter onto enemy vessels, and the flaming shower of sparks from the bomba marked the efforts of the Spanish vessels. The galleasses used their oars to wear ship as required to bring their stern, broadside or bow guns to bear on the targets offered, while the great height of their wooden sides rendered them practically immune to Turkish efforts to board them.

The goal of both fleets was to envelop the other, and fierce fighting raged on the flanks of each line. Gunpowder and thick armour began to make a difference in the Christians’ favour. As the Turkish marines perished, another calamity befell their ships. The Christian slaves on the benches of the Turkish fleet began availing themselves of weapons dropped in the carnage and attacking their former masters. While the ships were so embroiled, they lost all propulsion and hope of manoeuvre or escape.

Still the Turks fought on. Ali Pasha’s command squadron forced its way through to a cluster of Christian flagships in the centre of Don Juan’s line. Even the commanders became involved in the fighting: a septuagenarian Venetian nobleman too weak to span his own crossbow picked off individual Turks from the masthead while Ali Pasha himself bent a bow in the final surge of the fighting.

#

Faced with the very real threat of destruction in the forthcoming battle, the Venetian Republic added a new and innovative element to their preparations. By one recounting, six of the largest merchant galleys in the Venetian state-operated fleet stood by in one of the Arsenal’s storage basins while the preparations for the impending battle reached a fever pitch. It occurred to some inspired soul that these huge vessels could be used to carry freight rather more lethal than their usual cargoes of silks and spices.

No other shipyard in the world could have effected so sudden and drastic a conversion. The traditional emphasis on bow armament shifted under the pressure of necessity. Workman equipped the six galeazas (large galleys), with specialized fighting structures at the bow, the stern and along the sides to hold the largest cannon available from the Republic’s stockpiles. The resulting ‘galleass’ was quite literally a castle on the sea. At the bows of the ships, the high, protected forecastles bristled with cannon. These were balanced by similar armament in the substantial aftercastles. Nine or so periers, or full cannon, jutted out along each side – the guns and their carriages were mounted above, below or even among the oarsmen. On a lighter galley meant for speed and manoeuvre, such weaponry could never have been accommodated. With the creation of the galleass, however, the broadside was born.

Our detailed knowledge of the construction of the galleasses comes from specifications for later versions of these formidable hybrids. These were 49m (160ft) long and 12m (40ft) wide – twice as wide as the lighter galleys. Six men pulled each of the 76 heavy oars, and the decks were protected from boarding by the high freeboard, the long distance from the water to her deck being a difficult obstacle for an attacker to surmount. A galleass’s battery probably contained five or so full cannon firing a ball weighing 501b (22.7kg); two or three 251b (11.3kg) balls; 23 lighter pieces of various sizes and shapes; and around 20 rail-mounted swivel guns, used to slaughter rowers and boarding parties. The heaviest Venetian galleasses could fire some 3251b (147.4kg) of shot in every salvo. Five standard galleys would have been required to carry a similar armament.

The new leviathans did require towing by their smaller counterparts to achieve any sort of speed of manoeuvre – but this was no problem in a large fleet of galleys; the wind could provide the same impetus it gave to Edward III’s cogs at Sluys. Certainly on later examples, three huge lateen sails, each on its own mast, loomed above the deck. The exact size and armament of the six prototype galleasses at Lepanto is not known, but their performance is well documented. The Venetians were about to surprise the Turks.