The first bombs dropped from a heavier-than-air aircraft were grenades or grenade-like devices. Historically, the first use was by Giulio Gavotti on 1 November 1911, during the Italo-Turkish War.

In 1912, during the First Balkan War, Bulgarian Air Force pilot Christo Toprakchiev suggested the use of aircraft to drop “bombs” (called grenades in the Bulgarian army at this time) on Turkish positions. Captain Simeon Petrov developed the idea and created several prototypes by adapting different types of grenades and increasing their payload.

On 16 October 1912, observer Prodan Tarakchiev dropped two of those bombs on the Turkish railway station of Karağaç (near the besieged Edirne) from an Albatros F. 2 aircraft piloted by Radul Milkov, for the first time in this campaign.

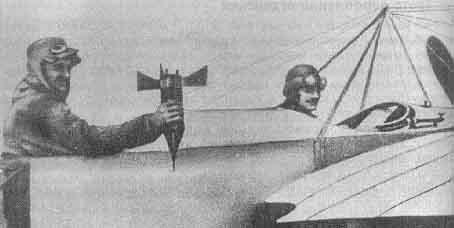

After a number of tests, Petrov created the final design, with improved aerodynamics, an X-shaped tail, and an impact detonator. This version was widely used by the Bulgarian Air Force during the siege of Edirne. A copy of the plans was later sold to Germany and the bomb, codenamed “Chataldzha”, remained in mass production until the end of World War I. The weight of one of these bombs was 6 kilograms. On impact it created a crater 4-5 meters wide and about 1 meter deep.

3 November 1912 – 26 March 1913

The siege of the Turkish city of Edirne – the former Ottoman capital – in the winter of 1912–13 was a remarkable victory for the small Bulgarian army against that of its much larger Turkish neighbour. But it is perhaps most memorable as the battle in which bombs were dropped from an aeroplane for the first time. Grenades had been thrown at Turkish soldiers by an Italian pilot in the Libyan War of 1911–12, but not bombs. A Bulgarian airman and engineer, Simeon Petrov, modified grenade shells by adding stabilizing fins and a fuse, creating what came to be known as the ‘Chataldzha’ bomb. There is some dispute about who first dropped them. The claim is usually given to the Bulgarian observer, Lieutenant Prodan Tarakchiev, flying in an Albatros F-2 aircraft piloted by Radul Milkov, who is said to have dropped bombs on Karaagac station on 16 October 1912 near the besieged city of Edirne. Another account has Major Vasil Zlatarov dropping the bombs from an aircraft piloted by an Italian volunteer, Giovanni Sabelli, on 17 November 1912. Whichever is correct, the Bulgarian air force, with its twenty-three aircraft, launched the long century of aerial bombing that followed.

The air attacks took place during the First Balkan War, in which an alliance of Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro took advantage of the fact that the Turkish Empire was engaged in war with Italy in North Africa. The aim was to expel Turkey from its remaining European territory, which stretched from Constantinople to the Adriatic coast of Albania. The war was launched by Montenegro on 9 October 1912, but the armies of the other three allies joined soon afterwards, rapidly driving the Turkish forces from the frontiers. In four weeks, Bulgaria moved its army of 400,000 a distance of 260 kilometres (160 miles) against collapsing Turkish resistance until it was only 65 kilometres (40 miles) from Constantinople on the fortified Çatalca Line. By 3 November, the city of Edirne (Adrianople) was surrounded by the 2nd Bulgarian Army under General Nikola Ivanov, supported by units of the 2nd Serbian Army led by Field Marshal Stepa Stepanovi´c. There were 154,000 troops surrounding the town, together with 520 guns. Inside the city, one of the most heavily fortified of Turkish settlements, were an estimated 50,000 soldiers commanded by Mehmet Sükrü Pasha, but the flight of Turkish and Muslim refugees had doubled the civilian population to 150,000.

Edirne held a special place in Turkish culture as the former capital of the original Ottoman state and it quickly became the symbol of Turkish resistance to the Balkan League. The press highlighted the plight of the encircled population, short of food and, after the supply was cut off by the Bulgarians in November, short of water, too. The disaster shocked Turkish opinion. One senior officer later recalled that Turkey regarded Bulgaria as a nation ‘that did not know about anything except raising pigs’, but the Bulgarians proved adept and hardy soldiers and were soon being compared with the Japanese or the Gurkhas – famously tough and effective fighters. Conditions in the city quickly deteriorated as salt and sugar disappeared and rations were limited to bread and cheese. Soldiers had little to eat and became, according to one eyewitness, ‘inhumanly emaciated’. On 15 November, the Bulgarian air force initiated another aspect of future air power by dropping leaflets over the city calling on the garrison to ‘come and surrender’. It was two days after this that bombs were dropped for the first time on the town, an inauspicious start to the long history of civilian bombing from the air. The bombing was reported in Turkey as an outrage, but in reality it was only a gesture. On 2 December a delegation came from the Bulgarian lines asking Mehmed Sükrü to surrender. ‘We have not yet given battle,’ he retorted, but three days later a ceasefire was agreed along all fronts.

The pause gave the soldiers and citizens in Edirne no respite, since the Bulgarian and Serbian troops remained in place. The garrison expected food to be sent from Constantinople but nothing came, while 180 trains laden with food and supplies passed along the city rail route to supply the besieging forces. In January 1913, unable to accept the surrender of Edirne in a future peace settlement, a group of young officers staged a government coup and rejected the proposals then under consideration. On 4 February the siege began again, with Bulgarian artillery blasting the centre of the city incessantly. ‘Being besieged within a fortress,’ wrote Rakim Ertür in his journal during the battle, ‘is an experience that resembles none other on earth – neither prison, nor exile.’ The hungry population begged and stole food, increasingly anxious about what surrender might mean. By late March, the Bulgarians judged that the garrison was too weak to resist any longer. On 24 March, the troops covered the metal of their uniforms and weapons with tissue to deaden noise and to conceal their gleam, and that night stormed the city. They captured the fortified enclave and the following night captured the fortress in the city centre. Mehmed Sükrü surrendered the following morning. The Bulgarian army allowed three days of looting and violence against the population, no doubt a deliberate echo of the Islamic law that specified this exact length of time for seizing booty. For centuries the victims of Turkish atrocities, Bulgarians could see no reason not to repay their enemy in the same coin.

Edirne was to pass to Bulgarian rule following agreements reached in a peace conference in London, but the Balkan states fell out over their territorial gains and while Bulgaria was under attack from her recent allies, Turkish forces crossed the newly agreed frontier and reoccupied Edirne on 22 July 1913. It has remained in Turkish hands, except for a brief Greek occupation in 1920–22, ever since. One of those who reoccupied the city was a young colonel, Mustafa Kemal, destined to go on to become modern Turkey’s first ruler. The ‘Chataldzha’ bomb also enjoyed a later reputation. The design was passed on by the Bulgarians to the German army and became the prototype for German bombs in the First World War. What began as a modest and militarily insignificant engineering experiment grew, within a generation, into the most destructive weapons yet devised.