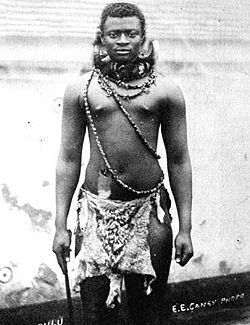

King Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo

German interest in the Zululand coast during the mid-1880s prompted British action to secure the area. In October 1886 the New Republic Boers agreed to limit their territorial ambitions and dropped their protection of Zulu King Dinuzulu. In January 1887 a British commission defined the boundary of the New Republic, and in May the Reserve Territory and central Zululand became the British Colony of Zululand. Extending the indirect rule system from Natal to Zululand, colonial officials planned to gradually diminish the power of traditional leaders. Dinuzulu refused to appear before the British Resident Commissioner, and local chiefs complained about having lost authority over their people within the New Republic. The payment of a colonial stipend to Zulu chiefs divided Usuthu (royalist) leaders as some like Mnyamana accepted it that represented a sign of submission but Dinuzulu rejected it. British regular soldiers, a company of mounted infantry and a cavalry squadron, were ordered into Zululand in August 1887 to support the mostly black Zululand Police. Dinuzulu repeatedly resisted efforts by colonial officials for him to return cattle seized from a subordinate ruler. In December the British allowed antiroyalist leader Zibhebhu and 700 men—they did not initially bring women and children as they knew they would have to fight—to return to their old area in Zululand where they pushed out the Usuthu. In early 1888 the demarcation of a border between the Usuthu and Zibhebhu’s Mandlakazi by colonial officials clearly showed a bias toward the latter. Dinuzulu withdrew to caves around Ceza Mountain with over 1,000 armed men and Usuthu leader Ndabuko, the king’s uncle, assembled another 1,000 and vowed to destroy Zibhebhu.

Tensions were increased by the upcoming June 1 deadline for payment of hut tax. On June 2 a colonial patrol of 66 Zululand Police, 160 mounted British regulars, and 400 Zulu levies from Mnyamana approached Ceza Mountain to arrest Dinuzulu but were driven off. A few days later Shingana, another uncle of Dinuzulu, left the New Republic with 1,000 men to support the Usuthu rebels around the White Mfolozi River. With colonial officials calling for reinforcements, British forces in Zululand increased to 300 cavalry, 120 mounted infantry, 440 infantry, 160 Zululand Police, and 200 Sotho cavalry supported by two field guns and two Gatling guns. On the morning of June 23, Dinuzulu and Ndabuko led 4,000 men in an attack on the small colonial fort at Ivuna protected by a few Zululand Police inside and Zibhebhu’s 700 men outside. Although the Usuthu employed the usual ‘‘chest and horns’’ tactic, Dinuzulu led around 30 horsemen with guns, some of whom were Boers with blackened faces, who charged at the centre of Zibhebhu’s battle line. Outnumbered and outflanked, the Mandlakazi lost around 300 men though Zibhebhu escaped. Capturing 750 cattle, the Usuthu, who had only 20–30 men killed, returned to Ceza Mountain pursued by a few mounted Zululand Police. A column of 500 imperial troops, Zululand Police, and Sotho cavalry reached Ivuna the next day and evacuated its inhabitants. The retiring force was joined by Zibhebhu along with 200 men and 1,500 women and children. A full-scale rebellion broke out along the Lower Mfolozi River as white traders and the local magistrate were attacked. On July 2, a colonial force of 87 Zululand Police, 190 mounted British regulars, 140 Sotho cavalry, and 1,400 Zulu levies surrounded Shingana’s 1,000 Usuthu in the open highlands at Hlophekhulu. Another colonial contingent, consisting of a British cavalry squadron, a mounted infantry company, and 400 Zulu, was positioned five kilometers away at Lumbe Hill to prevent a Usuthu withdrawal. At Hlophekhulu 300 Usuthu were killed and the rest scattered in all directions with Shingana escaping to the New Republic. Throughout the rest of July and into August several colonial columns intimidated Zulu communities along the Lower Mfolozi River and the coast. In July 1888 the New Republic joined the South African Republic. On August 11, a punitive expedition, led by Captain R. S. S. Baden-Powell, accidentally wandered across the Transvaal border and mistakenly attacked a group of loyal Zulu. Usuthu confidence was broken by the defeat at Hlophekhulu and Dinuzulu’s supporters began to disperse. By the end of September imperial military units had withdrawn from Zululand and colonial police took over the hunt for Dinuzulu. After a short stay in the South African Republic, Dinuzulu and other fugitive Usuthu leaders surrendered at Pietermaritzburg in Natal in November but were quickly escorted back to Zululand where they were found guilty of treason and imprisoned. Dinuzulu, Ndabuko, and Shingana were exiled on St. Helena from 1890 to 1898.

In the British colony of Natal, which had been granted responsible government in 1893, 100,000 Europeans and a similar number of Indians dominated around 1 million Africans. Since the African inhabitants of the original Natal colony had never been militarily conquered, European officials ruled indirectly through African chiefs. The neighboring Zulu Kingdom had been defeated by the British in 1879, torn apart by civil war in the 1880s, and then quietly annexed to Natal in 1898. Although the mineral revolution in the interior led to an expansion of settler commercial farming in Natal, the mines pulled away African labor. The years immediately after the South African War were characterized by economic recession. In 1903 the Vryheid District of the Transvaal, which had been the New Republic in the 1880s, was joined to Natal. In 1905 theNatal legislature, controlled by white farmers, imposed a poll tax on the adult male African population, on top of the existing hut tax paid by homestead heads. The purpose of the poll tax was to generate revenue for the Natal administration and to propel more African young men into wage labor.

In early February 1906 a small colonial police patrol, sent to investigate an African gathering to protest the poll tax south of the colonial capital of Pietermaritzburg, became involved in a skirmish and two white policemen were killed. The presence of independent African Christian church members in this incident served to confirm white paranoia that such movements meant to provoke resistance. Martial law was declared and a colonial army under Colonel Duncan McKenzie moved through southern Natal flogging people, burning homesteads, and seizing livestock. Seventeen men accused of having been involved in the killing of the policemen were either shot by firing squad or hung. To the north, Chief Bambatha’s people, most living as tenants on white farms, faced pressures from crop failure, increased rents, and now the poll tax. When colonial authorities deposed him as chief in early March, Bambatha fled to the bush, where he rallied several hundred men and abducted his uncle who had been appointed to replace him. On April 4, his followers shot at a white magistrate sent to investigate and the next day they ambushed a police column at Mpanza, killing three Europeans. Moving east across the Thukela River into what had been the Zulu Kingdom, the rebels took refuge in the Nkandla Forest. Some chiefs who lived in the sheltered valleys to the north and west of Nkandla, similarly angry at colonial demands, joined Bambatha. However, those of the southern open grassland stayed out of the rebellion as their communities would be exposed to colonial firepower. A volunteer settler militia was formed, including a contingent of 500 mounted men from Transvaal, a Maxim gun and crew sponsored by Castle Beer Company, and Sergeant Major Gandhi’s Indian stretcher bearers. On May 3, the Natal Field Force, consisting of around 5,000 armed men and 150 wagons, left Dundee and moved toward the Nkandla Forest in search of Bambatha. Throughout May the militia destroyed Zulu communities and fought a series of skirmishes with the rebels. On the night of June 9–10 the militia discovered Bambatha’s camp on the Mome River, artillery was moved to high ground, and the the colonial troops attacked at dawn. Bambatha’s force was defeated and the chief ’s severed head subsequently brought around the colony to intimidate Africans. Of Bambatha’s 12,000 followers, 2,300 had been killed and 4,700 taken prisoner.

Another phase of the rebellion began on June 19, when 500 armed Africans attacked European stores and militia 50 kilometers south of the Nkandla Forest in the densely populated valleys of the Maphumulo area. Over the next three weeks, fighting spread east to the settler farms near the coast and to the south through the sugar-producing areas close to the port of Durban. Once again, the rebels attempted to conceal themselves in densely forested valleys to reduce the effectiveness of colonial horses and firepower. By the end of June the number of colonial soldiers in Maphumulo was increased from a few hundred to 2,500, with many returning from operations against Bambatha in Zululand. In early July, after failing to encircle a Zulu rebel group that had slipped away, McKenzie’s militia went on a rampage in the Mvoti Valley looting, burning, seizing livestock, and indiscriminately shooting any fleeing African, including some ‘‘loyalists.’’ McKenzie then learned that a large rebel force was camped in the Izinsimba Valley. On July 8, he repeated his favorite tactic of a night march to position artillery and Maxim guns on the high ground in support of an infantry assault at sunrise. In all, 447 Zulu, including key leaders such as Mashwili, were killed and the militia sustained no losses. The colonial scorched earth campaigned continued throughout the rest of the month and brought the rebellion to an end. Justifying extremely heavy African casualties, colonial authorities claimed that supposedly primitive people did not understand the destructive power of modern weapons. During the campaign, colonial soldiers defended their use of ‘‘dum dum’’ bullets, internationally banned because of the terrible wounds they inflicted, as necessary because savage African warriors could not be stopped by normal ammunition.

Hundreds of Africans were brought before martial law courts, and after October 1906, conventional courts, where they were convicted of treason and usually sentenced to flogging followed by two years of hard labor on the Durban docks or northern Natal mines. Among these was Dinuzulu, who had stayed out of the fighting but was convicted of treason and sentenced to four years in prison for harboring Bambatha’s family. According to historian Jeff Guy, the Natal settler community was supremely confident following the South African War and the overreaction to the Zulu rebellion represented ‘‘the act of conquest that the colonists had been unable to carry out when Natal was established sixty years before.’’