Battle of Killiecrankie

The war that Dundee declared in the name of James VII against the government forces is called the First Jacobite Rebellion, and the army of mostly Highlanders that he gathered together came not from the larger clans and magnates, but from smaller marginal clans such as the Macdonalds of Keppoch, Clanranald and Glencoe, the Stewarts of Appin and the MacGregors—although the latter adhered too late to participate in the Battle of Killiecrankie. The Keppoch and Glencoe Macdonalds and the MacGregors were regarded as little better than cateran bands, but in their defence it has to be said that previous Stuart kings in alliance with some of the Campbells had marginalized them by unremitting persecution earlier in the seventeenth century. A more respectable ally and a valuable lieutenant was Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheill, who was 60 years of age and had fought in the Glencairn Rebellion of the 1650s. Dundee found him to be a valuable advisor.

Dundee was an experienced soldier, well versed in modern warfare, and had studied the culture of the Highlanders enough to know that their methods of warfare were comparatively primitive. He had an extraordinary ability to make the best use of the Highland warriors, but he had to adapt himself to their expectations, habits and limitations, as well as strengths. To this he added his own flair for histrionics in leading troops in battle. He had feared that the Highlanders might have grown less alert during the years of relative peace preceding Killiecrankie. When Dundee proposed to impose modern military discipline upon them, the Lowland officers and the younger Highland chiefs (some of whom were mere boys) supported the idea, but Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheill advised that the Highlanders would make more effective fighters if they retained their own methods of warfare and were commanded by their own leaders. This, Locheill observed, had proved the best course of action under Montrose. He also thought that the Highlanders would lose their courage if reduced to a state of servitude like other European soldiers. In any case, the introduction of modern discipline would be time-consuming, and Locheill assumed that Dundee’s army would not be in existence for very long.

Dundee had no easy time holding together his army of clansmen, and he was unable to assemble all of them in time to fight at Killiecrankie. One of the clan chieftains who had joined Dundee, Macdonald of Keppoch, took the opportunity of settling some scores with an old enemy, Sir Lauchlan Macintosh, who had remained neutral in the war. Keppoch slipped away with his followers and ravaged the Macintosh country. Upon hearing of this, Dundee delivered a stinging rebuke to Keppoch, and told him he did not want him serving under him. Keppoch begged Dundee to keep him on, and said he would not have attacked Macintosh had he not thought him the king’s enemy, and promised strict obedience thereafter. When members of the Clan Cameron sought to revenge themselves on the Grants for hanging one of their kinsmen, they killed a Macdonald. When Macdonald of Glengary complained of this to Dundee, the latter refused to punish the Camerons because, as the Highlanders were not regularly paid and subject to discipline, and were expected to live on their own resources, he did not regard them as being strictly under his command. Moreover, they were ignorant of military law. Dundee also told Glengary that the provocation had been great because the Macdonald who had been hanged together with the Grants were adherents of the king’s enemies. If he were to punish those accused by Glengary, the Highlanders would cease to fight for the king’s cause. The duplicitous John, Lord Murray, heir of John, first marquis of Atholl, attempted to deceive his 1,200 followers during his father’s absence and make them think that they were going to fight for King James, when he was actually in communication with General Mackay and intended to support William II and III. When his followers pressed Murray for a straight answer about his allegiance, he refused to reply. They deserted him en masse, and declared their loyalty to James.

General Mackay had very little confidence in the army that the Scottish Convention Parliament of 1689 had authorized. Ten regiments of foot consisting of 6,000 men, one regiment of dragoons of 300 men and twelve troops of horse containing 600 men were to be raised. Command of these units was entrusted to peers and gentlemen with no military experience. Furthermore, the commanders of these units, Mackay complained, were allowed to choose all of their own officers upon the basis of popularity and ability to raise soldiers rather than competence and experience. The only reliable units in the Scots force were the three regiments from the Scots Brigade of the Dutch army, but they were much reduced in strength. One new regiment that did stand out was that raised by the 20-yearold James Douglas, earl of Angus, son and heir of James, second marquis of Douglas, which came to be known as the Cameronians and who later gave a good account of themselves fighting the remnants of Dundee’s army in the Highlands. The Cameronian Regiment was originally comprised of members of the Cameronian sect which had separated from the Kirk in 1680. They were all raised in a single day without beat of the drum or payment of a bounty, for the purpose of guarding the Scottish Estates.

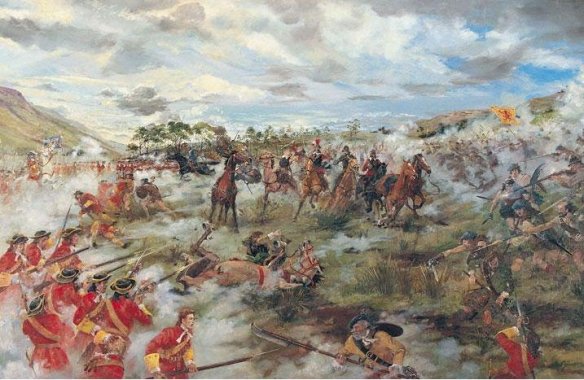

Both the Jacobite and Williamite armies suffered from serious disadvantages prior to the Battle of Killiecrankie. Dundee was short of cavalry, and was not very successful in raising more horse in the eastern Highlands. He had also hoped to be reinforced by King James from Ireland, but then he got news that English ships had captured a shipment of arms, munitions and provisions being sent to him by way of the Isle of Mull. His Highlanders and the Irishmen led by General Alexander Cannon were already half-starved, but they followed Dundee cheerfully. This compelled him to forage in the Lowlands at the foot of Glenlivet. It was not much easier for Mackay to raise cavalry. He did not trust his dragoons, and the core of his horse consisted of 100 English troopers from Lord Colchester’s Regiment who, with their horses, found it very fatiguing negotiating the mountainous terrain. They were short of fodder, and of little use for gathering intelligence. At Edenglassy, Dundee came upon a store of provisions intended for Mackay, but also learned that Mackay’s reinforced army was marching towards him. Not wishing to expose his Highlanders to cavalry, which was the one thing they feared, Dundee decided to withdraw to the Grampian Highlands on the pretext that they were joining other clans. He conducted an orderly retreat along the banks of the River Spey and its tributary the River Garry into Badenoch. Dundee’s men did not complain of their hunger, because their general shared the same diet and walked beside them. The decision was taken to fight at the pass of Killiecrankie, before Mackay, whose army was already half as large again as Dundee’s, could bring up reinforcements. The Highlanders were on the heights above the pass, and fell upon Mackay’s dragoons and infantry as they came through it. This was ideal terrain for a classic Highland charge—casting aside their plaids, they charged down the hillside, fired their muskets and pistols and fell upon Mackay’s men with broadsword and target. They fought, not in rank and file, but as clans. Mackay’s forces were defeated, but it was a pyrrhic victory, because one-third of Dundee’s army was killed, another third wounded and the remainder dispersed by going after Mackay’s baggage train or were too exhausted to pursue the retreating army. Worst of all for the Jacobites, Dundee, who did not heed the wishes of his officers to remain behind cover, was killed at the end of the battle. William’s government in Scotland was safe, and Mackay still had an army with which to pursue the Highlanders.

Killiecrankie may have been a costly victory, but having become part of Jacobite legend, it was enough to encourage continuing resistance in the Highlands. In August 1689 the Cameronian Regiment, which was garrisoned at Perth, marched to Dunkeld at the entrance to the Highlands and fought a battle in which a much smaller Williamite force, numbering 800 and consisting mostly of the inexperienced Cameronians, blocked the advance of a much larger Jacobite force of at least 3,000 men led by the Irish general, Alexander Cannon. The Jacobite army included remnants of Dundee’s army and the Atholl Highlanders who had deserted their colonel, James, Lord Murray. The Jacobites were still able to field an army the next spring led by Major-General Thomas Buchan, but their resistance to the Williamite conquest of Scotland was ended by the Battle of Cromdale, near the modern Grantown-on-Spey, on 1 May 1690.

Following the Battle of Killiecrankie, Hugh Mackay went to Ireland where he fought alongside William of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne. William praised Mackay’s gallantry and conduct on that occasion, and asked him why he had not displayed the same characteristics at Killiecrankie. Mackay said that he had much underestimated the fighting qualities of the Highlanders, and that if William had faced Highland soldiers at the Battle of the Boyne he might well have found it more difficult to cross the river. At the end of the First Jacobite Rebellion William allowed Dundee’s officers, some 150 in number, to enter the French army. They formed a company of reformadoes serving as gentlemen volunteers, and saw action at Perpignan on the Spanish border, and later on the Rhine. Most of them died of wounds or disease. After 1689 the Highland charge lost much of its power of shock, because the firepower of the British infantry doubled with the replacement of firelock muskets with flintlocks, and the widespread use of socket bayonets which had replaced pikes and plug bayonets and which provided a more adequate defence against cavalry charges.

The conquest of Scotland gave William control only of the Lowlands. He did establish a military presence at Inverness and Fort William (Inverlochy) in the Great Glen, but because of his lack of interest in Scotland and his overriding concern with the prosecution of the Nine Years War, he neglected to follow up his military victories, and no Scottish or British government really governed the Highlands, where Jacobitism remained active as a protest against the Edinburgh and London regimes, until after the defeat of the Rebellion of 1745.