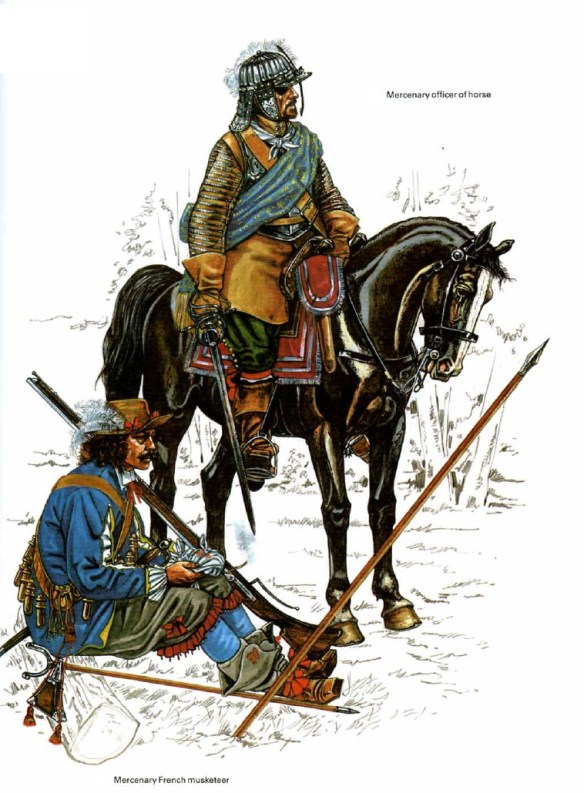

In the early years of the war, Parliament lost popular support through employing brutal foreign mercenaries and soldiers of fortune. Heavy resentment against the high level of pillage, looting and rape by foreign mercenaries – the worst offenders were probably the Germanic and Bohemian buccaneers who fought for the Puritans.

Mark Stoyle’s[1] ethnic analysis is very fine, not just in the areas one might expect, relating to Scotland, Wales, Ireland and Cornwall, but in his careful winnowing of the contemporary sources that throws up combatants hailing from France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Scandinavia, Poland, Spain, the Balkans and even Iraq (or Mesopotamia as it then was). Stoyle admits that the number- crunching and quantification beloved of a certain kind of historian will always elude the student of foreign mercenaries in the English Civil War, but he clearly establishes that the racial composition of the combatants is an unjustly neglected area and that the English Civil War was in part an expression of English chauvinism, as much to do with ethnicity and national identity as religion or economics.

Some had no particular preference for either party, but joined up with the first army which happened to come along, in the hope of pay and plunder. Captain Carlo Fantom, one of the hundreds of foreign mercenaries who flocked to England during the Civil War, frankly admitted that ‘I care not for your Cause, I… fight for your halfe-crowne[s], and your handsome woemen’.

Several traits are apparent in the two armies which gathered in autumn 1642. Firstly, the senior ranks were dominated by men who had previous military experience. It has been estimated that, of those present at Edgehill, at least 60 parliamentarian and 30 royalist officers had fought on the Continent over the previous decades. Although the Stuart kingdoms had largely remained at peace during the opening decades of the 17th century, untold numbers of English and Welsh men, both elite and non-elite, as well as large numbers of Scots – one historian has put the figure at around 25,000 Scots in total, perhaps 10 per cent of that country’s adult male population – had seen service abroad during the Thirty Years’ War, fighting as volunteers or mercenaries. Secondly, there was a conspicuous number of Scottish officers, particularly on the parliamentary side. Thirdly, the two overall commanders, Charles I and the Earl of Essex, had far less experience than most of those directly under them; Charles I had none, for he had not led troops in person during the French or Spanish wars of the late 1620s or the Scots’ Wars of 1639-40, while the parliamentary lord general had some experience as a colonel in the Dutch infantry during the 1620s as well as in the Scots’ Wars. Fourthly, most senior commanders were men of fairly mature years, into middle age in a 17th- century context; indeed , several, particularly on the royalist side, were rather long in the tooth by 1642. Assessment of royalist and parliamentary armies later in war confirm this trend, showing that most officers ranked colonel and above were in their 30s or 40s.

[1] Soldiers and Strangers: An Ethnic History of the English Civil War

Mark Stoyle, University of Southampton

New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005

ISBN-13: 9780300107005; 320pp., price £25.00

| Book: | Soldiers and Strangers: An Ethnic History of the English Civil War

Mark Stoyle, University of Southampton |

| Reviewer: | Martyn Bennett,Nottingham Trent University |

| Citation: | Bennett, M., review of Soldiers and Strangers: An Ethnic History of the English Civil War by Mark Stoyle (review no. 552) URL: http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/ paper/ bennett.html Date accessed: 14 May 2008 |

Review

Wow! It is rare that a view of the civil wars and revolutions of the mid-seventeenth-century British Isles can evoke such a reaction. The historiography of the period is full of dramatic shifts in perception. From rebellion to civil wars to revolution to the ‘new British’ history and its three or four or five kingdoms context (or, my favourite, the four nations context); from class conflict to shifts of wealth within class, we have seen major movements in the way the period has been understood. Mark Stoyle’s latest book has the potential to do no less than turn our current views on their heads. Stoyle presents the wars as a conflict that would fit the description, set out by UN chef de cabinet Mark Malloch Brown at the recent British Council Annual lecture, of a modern conflict; that is one that did not recognize national boundaries but which involved religions or ethnicities. The English Civil War, in this exciting approach, becomes resolved on the issue of the English against the Celtic nationalities that bordered, or in Cornwall’s case inhabited, England. The king’s army became associated with these foreigners—Scots, Welsh, Cornish and Irish—whom he used in his war against Parliament. Parliament, in contrast, represented England and the English.

That such an argument can arise should be no surprise. The ethnic qualities of the conflict have been brought to the fore as a direct result of the ‘new British’ approach. Ever since J. G. Pocock began the discussion of the Britishness of the seventeenth century in the 1970s, we have all been turned in such a direction. Of course we English historians were being a bit slow. David Stevenson was a pioneer of this approach in the 1970s when he demonstrated clearly the Scottish origins of the civil wars and revolutions. Irish historians such as Aiden Clark and Nicholas Canny were also keenly aware of the British Isles context, but it was only during the late 1980s, when historians like Conrad Russell and Ann Hughes launched examinations from an English perspective, that momentum developed and ‘Johnny come latelies’ such as myself threw themselves on the bandwagon. Of course, in a sense even the Irish and Scottish historians, who were clearly instrumental in redirecting us away from the Anglo-centric approach, were latecomers.

In the 1950s, C. V. Wedgwood’s two volumes on the 1630s and 1640s wove a complex narrative of interlocking national stories. Coming in an era when increasingly sophisticated analyses of social structures were being produced, the work was wrongly dismissed as a narrative work, and the ‘British Islesness’ of the books forgotten. Back in the seventeenth century, the notion of exclusivity could not exist. Neither Clarendon nor Lucy Hutchinson would have recognized the concept of the English Civil War. Of course there cannot be a complete balance of effort and responsibility. The excellent bi-partisan approach of Jane Ohlmeyer and John Adamson in History Today in November 1998 presented what appeared to be irreconcilable approaches to the issue of centrality. Ohlmeyer was arguing for a pan-national approach, Sommerville for the centrality of England. Both were right. The context and much of the action was within the British Isles; on the other hand the revolution of 1649 was English (and perhaps a bit Welsh). It certainly was not Irish or Scottish. The years 1649–1652 saw political initiative within the British Isles pass decisively from Scotland, from where it had arguably sprung since the 1590s, to England, paving the way, through a torturous process, to the Act of Union 1707. From this fervent debate springs Mark Stoyle’s latest work.

Mark Stoyle is the author of two books and a series of articles that make very important points about the civil war. During the 1990s he alerted us to the unique nature of the war in the south west in Loyalty and Locality: Popular Allegiance in Devon During the English Civil War (Exeter, 1994), and of Cornishness in ‘Pagans or Paragons? Images of the Cornish during the English Civil War’, English Historical Review, 111 (1996) 299–323. This region of England has been used and abused by English monarchy and government over the centuries. Used by monarchs to pack parliaments, Cornwall has several times made its political will known to London, particularly in the late-fourteenth and mid-fifteenth centuries. By the seventeenth century Cornwall seemed to be quiescent; with its language in decline and its populace quiet, it has been possible, if not to write it out of history, simply to write it into English history. Stoyle’s work pointed out that this was a mistake. The region remained distinctive; the civil war there was different. The local issues that shaped war in other areas of England were overtly political, and locally so, and war was moulded by a range of socio-political relations, often those contained within very small family networks. In Cornwall, there were cultural issues at play too. When Cornish troops baulked at crossing the Tamar, it was not the same as when the trained bands in other counties grumbled at leaving their county, claiming that they were brought together solely for the defence of their shire, perhaps because the soldiers rejected the politics of either the Royalists or Parliamentarians who had called them together. In the south west the issue was almost one of nationality. Naturally, this keen sense of identity worked two ways, for the troops who invaded Cornwall during war, from 1642 onwards, also saw the Cornish as distinctive. In a period where there was no concept of separate but equal, this was always a difficulty for those defined as ‘other’. Stoyle’s work is crucial to our understanding of this cultural aspect. This new book takes his work several steps further, by tying the Celticness of Cornwall into the Celtic fringe as a whole and viewing the ‘differences’ from both sides.

The book is divided into two principle parts. The first looks at the period 1642–1644 which Stoyle has termed ‘The Influx’, by which he refers to the impact of the Celtic troops allied to the Royalists (the Welsh and Irish) and (a faction within) the Parliamentarians (the Scots). The second section is headed ‘England’s Recovery’, and this looks at the way in which England defeated the foreigners and established its cultural freedom from them, and, furthermore, inflicted defeat and conquest upon them.

The book opens by looking at the origins of English concerns about its position amongst the Celtic nations and fringes and how this led to mixed reactions when the Scots invaded the north east in 1640. It is known that there was both a welcome for the liberators and concerns about this incursion by the traditional enemies. Stoyle points out that this came mainly from within the political Royalist group, but there were general concerns amongst a wider population too. For a year the occupying forces represented a national humiliation for the English and their departure from English soil was marked by celebration. Anti-Scots feeling was at the heart of the developing Royalist faction. Scotland had been an enemy nation allied to France until the previous century and the accession of James VI to the throne of England and Wales (and Ireland) in 1603 had been surprisingly peaceful given this animosity and the history of fractious relations on the borders. James’s reputation for the importation of Scotsmen into England was something else that did little of practical value to ease relations. With this background despair in England at Charles’s religious reforms would have had to be intense indeed to overcome antipathy. For this reason the political empathy of a few people, such as English Presbyterians, and the manipulation of the political scene by the king’s opponents, who could use the Covenanting Army as muscle, could never fully outweigh the problematic nature of an occupying force in the north east.

With the Scots entry into the English war in 1644 these problems returned to haunt the nation, and the Royalists again could use anti-Scottish feeling as a political hammer against Parliament. Scotland’s polity had originally attempted to play a mediating role between the factions in England, seeing peace and stability in a reformed English and Welsh polity as a defence against Charles I’s attack on the kirk. When the king rejected Scotland’s approaches, and moreover appeared to be the likely victor in the war in England and on the verge of an alliance with the Catholic Confederation of Kilkenny, Scotland accepted the approaches of John Pym and the Westminster Parliament. The consequences of this alliance, however, were the acceptance both of creating an assembly of Divines to decide the future of the church in England and a signing of the Solemn League and Covenant that went far beyond a political alliance and created, in effect, a joint spiritual union in defence of the Presbyterian kirk. This would drive a wedge between the allies that grew from a division in parliament and its armed forces between those who accepted and those who rejected the ‘drift’ to Presbyterianism in England and Wales.

Of course, within three months of England’s liberation from its erstwhile liberators in 1641 a new threat from the Celts emerged as Ireland descended into rebellion. This threat was far more that a Celtic threat, for the Irish were apostate unlike the Presbyterian brethren. No faction in England, other than perhaps a tiny Catholic minority, could possibly have welcomed the Irish as liberators had the much feared rebellion occurred. The Irish rebels certainly had no real intention of exporting their war to England, even if within the earshot of the population of displaced settlers some rebel footsoldiers declared the very opposite. This was a rebellion to enhance the status of the Roman Catholic Church and its members in Ireland; a rebellion aimed at restructuring an existing polity, not replacing it. Even at its most functionally radical height the rebels declared their loyalty to the king and the concept of a lawful parliament. The use of Irish troops in Britain, begun by Alistair MacColla in 1644, was part of Irish, not British, strategy, and was aimed at getting the Scots out of Ulster, not at putting the Irish into Scotland.

Nevertheless, seen from Britain the Irish were a Catholic vanguard that aimed to implant Catholicism in Scotland and, particularly, in England. With this mentality already firmly rooted by the early months of the rebellion, the arrival of troops from Ireland into Wales and England in late 1643 and early 1644 was viewed as terrifying. Stoyle very usefully analyses the reality of this incursion, which of course was far less dramatic than it appeared. The troops that came from Ireland were generally English soldiers who had been sent to Ireland in the wake of the rebellion to defeat it. They were of dubious loyalty as far as the king was concerned, and some, like George Monck, took the first opportunity to change sides. Moreover there were not that many of them, and Stoyle gives a salutary analysis of the numbers involved. Importantly, their impact was not massive; a good portion were defeated at the battle of Nantwich in January 1644, for example. Nonetheless, Westminster made a great deal of their presence and used them quite effectively as a hammer with which to beat the Royalists.

Once war began all the Celtic fringe nations became embroiled in the English fears of invasion. The prevalence of Welsh troops in the king’s army was particularly noted in the early stages of the war. This had origins in a general mistrust of the Welsh within England, and was given a sharp edge by the Roman Catholicism of the earl of Worcester, appointed lord lieutenant of Wales. Member of Parliament Oliver Cromwell commented that he feared another Ireland—a further papist rebellion—in Wales, in the run up to war in England, because of this laboured but perceived-as-potent link between Wales and rebellious Catholic Ireland. The Welsh Royalists were described in vitriolic terms as barbarous and thieving foreigners. That this affected the minds of the Welsh is undoubted; Stoyle suggests that there were fears amongst the Welsh that Parliament desired their extirpation in the latter stages of the war when its forces made significant incursions into Wales. There were occasions that would give rise to that expectation; the barbarous murder of the garrison at Canon Frome being just one example of seeming ‘special treatment’. Yet, to confuse matters, this massacre was carried out by Scottish troops, not English Parliamentarians.

The second part of the book, headed ‘England’s Recovery’, the title a genuflection toward Joshua Sprigge’s Anglia Rediviva, is the story of how Parliament’s victory was England’s victory against the various foreign malefactors brought in by the Royalists (and by a Parliamentarian faction). The word ‘patriot’, Stoyle argues, had come to be identified with Parliament, which had for centuries been identified with the nation, perhaps particularly with the south and east—coincidentally the region most distant from the Celtic fringe. This identification seems, according to Stoyle, to be found across the social spectrum and across the military divide, with soldiers and villagers identifying themselves, Parliament, and their cause as a part of a struggle for England. The war within the country was strangely seen, not so much as a war between king and Parliament, but as a war that kept the two apart; an intrusion by ‘outlanders’.

The anti-Scots feeling that pre-dated the civil war was now exemplified by attacks on the Scottish allies from Parliamentarians such as Prynne and Cromwell. In both cases, however, it is possible to question the extent of true anti-Scottish feeling rather than political and religious division. Cromwell’s attacks on Lawrence Crawford, for example, did not happen because Crawford was Scottish. It was instead Crawford’s intolerance as a Presbyterian that excited Cromwell’s ire, and some of the comments Cromwell allegedly made were ‘recalled’ by the earl of Manchester in his argument with Cromwell in late 1644 and early 1645. Cromwell’s description of Marston Moor as a victory of the Lord’s party was an inclusive claim, embracing English and Scots, and right into the 1650s Cromwell saw the Scots as ‘brothers in Christ’, even if they erred and bizarrely associated themselves with Charles Stuart. There is little doubt that the Scots saw Cromwell as an enemy, but again it was his sectarianism that was the issue, not nationality. Stoyle suggests that the New Model Army was created out of a quarrel that was anti-Scots almost as much as anti (English) Presbyterian and claims that Sir Thomas Fairfax was no ‘friend to the Scots’, yet this is the very man who, as baron Fairfax of Cameron, handed over his sword when faced with a war against the Scots. Clearly there are levels of complexity, and this Stoyle acknowledges, but he sees his way through with apparent clarity. On the other hand this very complexity may well limit the validity of the thrust of ‘England’s Recovery’. This recovery, Stoyle argues, could, from Cornwall and Wales, be viewed as more than a military or political defeat. Whilst victory, particularly in Wales, was a combination of conquest and conciliation, the outcome, it is argued, was a cultural defeat, at least in part. Stoyle records that this cultural victory was not actually pursued fully by the victors, who realized, for instance, that to explain themselves they had to publish in Welsh, just as lowland Scots had to publish in ‘Erse’ to communicate with those living in the highlands and islands.

It is a peculiarly English view to see the Celts as foreigners threatening England. King Charles was like his father in very few respects; his ability to see with a British perspective was one of them. Unlike James, who saw the opportunity to bring all nations together under one crown and polity, however, Charles saw them as an alternating set of resources to be used to secure governance over the whole. Remodelling the churches of Ireland and Scotland on English lines in the 1630s; using Irish, Welsh and English resources against Scotland in 1639–1640; using English, Welsh and Scottish resources to fight the Irish in 1641–1642; and, latterly, using Welsh, Irish and Scottish resources against England in the 1640s. If this perspective is correct then Stoyle’s argument is problematic, as was the argument about the conflict being one of religion as voiced in the 1980s. There was no consensus on the ‘war of religion’ idea because no one agreed that the Royalists were fighting one, even if Parliamentarians might have thought that they were. In this new case, Stoyle is arguing that Parliament was seeking to save England from foreigners, but we are left wondering if the foreigners were seeking anything but to restore the status quo ante represented by the king and Parliament in harmony; balancing not only contending political powers, but ethnic and cultural ones too. Nevertheless, this is an exciting and controversial account which demands to be read widely and wrestled with by students and academics. I return to my opening remark—wow!—this really is great stuff.

November 2006

Author’s response

I am most grateful to Dr Bennett for his kind review of my book and I take his point that the extent to which Oliver Cromwell and other English Parliamentarians acted out of a desire to further ‘national’ interests rather than religious ones between 1643 and 1646 is very hard to judge. My argument, I suppose, is that both factors were important in motivating the king’s opponents during the 1640s, and that both should be taken into account when assessing the events of this period. I am also happy to concede that Thomas Fairfax’s decision to lay down his commission as general in 1650, rather than lead an invasion of Scotland, suggests that, whatever his view of the Scots may have been during the late 1630s and early 1640s, his attitude towards them had mellowed considerably by the end of the latter decade. Turning to Dr Bennet’s final point, I can only agree with him that, while a frankly aggressive strain of chauvinism was frequently visible in the Parliamentarian ranks during the Civil Wars, this was rarely, if ever, the case on the Royalist side. The Welsh and Cornish soldiers who fought in such large numbers for the king were not, in my view, motivated by any desire to dominate their English neighbours: rather, they were seeking, as Dr Bennett himself puts it, ‘to restore the status quo ante’ and to reestablish a polity in which their cultural and religious traditions would be respected, as they had been in the past. It was fortunate indeed for posterity that the Parliamentarian leaders eventually came to appreciate this fact, and to ensure that Wales and Cornwall were won back through a policy of military strength and conciliation combined, rather than through the adoption of the much more ruthless methods which were advocated by some Roundhead soldiers and commentators.

November 2006