On the face of it, Russia is still an intimidating military power. It has one of the world’s largest armies, excellent Special Forces, and some remarkable modern weapons. The Shkval [Squall] torpedo, for example, is an underwater rocket that travels in a capsule of gas created by its specially designed cone. Fired from a super-silent submarine, it is one of the few weapons that could endanger an American aircraft carrier. So is the Moskit supersonic ship-launched missile. Russia’s new S-400 air defense system has twice the range of American-made Patriot missiles. The Topol-M is an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) with a multiple warhead. Unlike its liquid-fuelled counterparts that usually launch from vulnerable silos, it has a propulsion system based on much more stable solid fuel. Its can be kept in constant readiness, and launched from anywhere. Russia has hugely increased its military procurement budget: the latest published figures are for nearly five trillion rubles (roughly $190 billion) to be spent in the period up to 2015. The aim is to replace 45 percent of Russia’s arsenal with new equipment, with an emphasis on long-range nuclear weapons. Pride of place goes to a new submarine-launched ballistic missile, the Bulava, and to at least 50 new Topol-M land-based missiles.

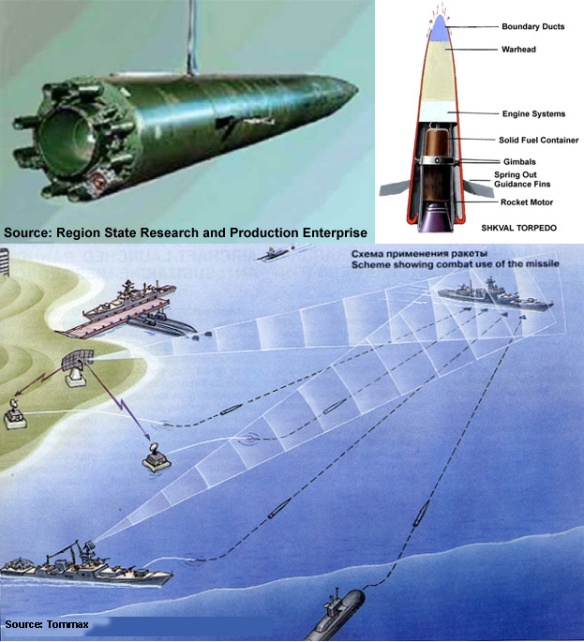

In the early nineties rumors circulated throughout the West about the latest ultimate weapon at sea, the VA-111 “Shkval,” or “Squall,” rocket-powered torpedo, initially deployed by the USSR in 1977 after seventeen years of development. Shkval was apparently first semiofficially mentioned in a 1995 issue of Jane’s Intelligence Review. According to that authoritative British journal, the solid-fuel rocket torpedo employed “redirected thrust ejected from its nose and skin” to create “a semi-vacuum bubble or `supercavity’” around it, permitting the missile to travel through the water at an incredible 230 miles per hour, about five times as fast as the best Western weapon. Advanced surplus Russian submarines, like the ultraquiet, diesel-driven Kilo class, are capable of carrying a number of Shkvals and could thus sneak up on unwary U. S. aircraft carrier battle groups and let fly. Fortunately, the Shkvals possess a limited range of only seventy-five hundred yards. But even once detected within that range, Kilo submarines could devastate American naval forces, since their Shkvals would reach target long before American ordnance could hit the Kilo. Ominously, China began purchasing Shkvals from Russia in 1998 together with four Kilos. Some intelligence analysts believed as early as 2003 that China “is building a navy capable of operating far from the Asian continent, armed with a combination of silent subs, supersonic nuclear tipped Stealth missiles, and the Shkval.” (In the late summer of 2006, press reports indicated that Iran was test-firing a variation of this weapon, called “Hoot,” together with a submarine-to-surface ballistic missile called “Thaqeb” during war games in the Persian Gulf.”) Steady Sino-Indian tensions over Tibet, Nepal, and other border areas, together with long-standing Chinese demands to incorporate Taiwan, could entice Beijing into a further substantial increase of its modest naval force.

But building an electronic-age naval fleet of even modest size, then maintaining and upgrading it for decades, can be a treasury-breaking enterprise. It demands, as we have seen, not only industrial competence of a high order in the construction phase but also sailors familiar and comfortable with the most advanced electronic systems and their use in the operational phase. By and large, the U. S. Navy has not sold or shared its advanced technologies. Ambitious young sea services have thus had to look elsewhere, and in most instances (the French Exocet missile being a major exception) the only readily available supplier has been the rusting Soviet fleet. The Indian, Chinese, and other world fleets have been forced to accept and adapt for use flawed Soviet designs, ships, and spare parts that will become increasingly scarce and worn out as the years progress. The state of play on the world ocean does not suggest that a serious challenge to U. S. sea power will materialize any time soon.