Italian air power

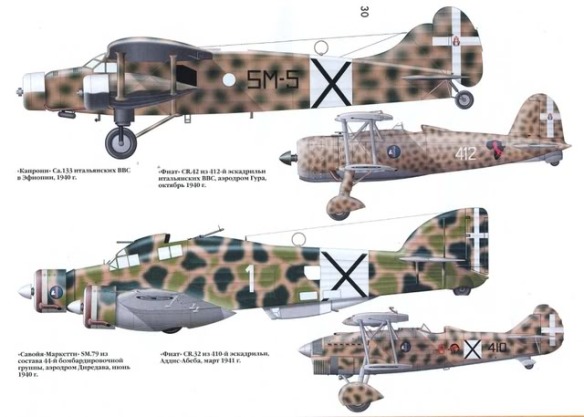

In June 1940, the Italian Royal Air Force (Regia Aeronautica Italia) in East Africa had between two-hundred and three-hundred combat ready aircraft. While some of these aircraft were outdated, in relative terms these were some of the best aircraft available to either side in East Africa in 1940. The Italians had Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 and Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 bombers and Fiat CR-42 fighters. In addition, the Italian aircraft were often based at better airfields than their British and Commonwealth counterparts. When the war began, Italian pilots were relatively well trained and confident of their abilities. But, cut off from Italy as they were, problems with lack of fuel, munitions, spare parts, and replacements eventually wore down the Italian air capability.

British Empire air power

The roughly one-hundred aircraft available to the British Empire forces in June 1940 were dispersed as follows: In the north (Sudan) were three Royal Air Force (RAF) bomber squadrons (Nos. 14, 47 and 223) equipped with obsolete Vickers Wellesley aircraft. A flight of Vickers Vincent biplanes formed from No. 47 squadron performed Army Co-operation duties and these squadrons were later reinforced from Egypt by No. 45 squadron (flying Bristol Blenheim aircraft). In Port Sudan there were six Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters. The air force’s role in Sudan covered shipping protection in the Red Sea (including anti-submarine patrols), air defence of Port Sudan, Atbara and Khartoum as well as close support for land forces. The No. 1 (Fighter) Squadron of the South African Air Force (SAAF) (equipped with Gladiators) arrived in Khartoum as reinforcement in August.

In the south (Kenya) were No. 12 Bomber Squadron SAAF (equipped with Junkers Ju 86 bombers), No. 11 Bomber Squadron of the SAAF (equipped with Fairey Battles), No. 40 Army Co-operation Squadron SAAF (equipped with Hawker Hartebees), No. 2 Fighter Squadron, SAAF (equipped with Hawker Furies), and No. 237 (Southern Rhodesian) Army Co-operation Squadron (equipped with Hawker Hardys).

Unlike the Italians, the aircraft available to the British and Commonwealth forces improved with time. But, as can be seen above, much of the equipment initially available tended to be older and slower. Even so, the British and Commonwealth forces managed to make do with what they had. The South Africans even pressed an old Valencia biplane into service as a bomber.

In East Africa Italian forces under the command of the Duke of Aosta had captured outposts in Sudan and Kenya and occupied British Somaliland soon after Italy had entered the war. Although they vastly outnumbered the British forces, most of whom had been raised locally, Aosta was demoralized by the Italian defeats in the Western Desert and at the moment of Britain’s greatest weakness he unwisely adopted a defensive posture. The British had also broken the Italian Army and Air Force codes and, armed with copies of Italian orders as soon as they were issued, Major-General William Platt launched an offensive into Eritrea on 19 January 1941 with 4th and 5th Indian Divisions. After weeks of hard fighting they captured Keren on 27 March, which proved to be the decisive campaign of the battle, and entered Massawa on 8 April. Meanwhile, on 11 February, Lieutenant-General Alan Cunningham launched an offensive into Italian Somaliland from Kenya using British East African and South African troops with startling success. After capturing Mogadishu, the capital of Italian Somaliland, on 25 February he struck north toward Harar in Abyssinia, which he captured on 26 March. A small force from Aden reoccupied British Somaliland without opposition on 16 March, to shorten the supply line, and joined with Cunningham’s force to capture Addis Ababa on 6 April. In just eight weeks Cunningham’s troops had advanced over 2,735 km (1,700 miles) and defeated the majority of Aosta’s troops for the loss of 501 casualties.

Even more spectacular were the achievements of Lieutenant-Colonel Orde Wingate, later to win fame as commander of the Chindits in Burma, who commanded a group of 1,600 local troops, known as the Patriots, whom he christened “Gideon force” Through a combination of brilliant guerrilla tactics, great daring and sheer bluff he defeated the Italian Army at Debra Markos and returned the Emperor Haile Selassie to his capital, Addis Ababa, on 5 May. British troops pressed Aosta’s forces into a diminishing mountainous retreat until he finally surrendered on 16 May, ending Italian resistance apart from two isolated pockets that were rounded up in November 1941.

The campaign in east Africa was important because the conquest of Ethiopia, Mussolini’s proudest achievement, had been undone and for the first time a country occupied by the Axis had been liberated. Another 230,000 Italian troops were captured and vital British forces were released for operations in the Western Desert. It was also the first campaign in which Ultra and the codebreakers at Bletchley Park played a decisive role, providing an invaluable lesson on the impact that intelligence could have on the outcome of an operation. Success in east Africa also had an important strategic consequence since President Roosevelt was able to declare on 11 April that the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden were no longer war zones and US ships were thus able to deliver supplies direct to Suez, relieving the burden on British shipping.