The first that Captain John Glossop knew about the terrible mistake he had made was when the salvo of shells screaming through the air hit HMAS Sydney, killing four sailors and wounding a dozen more. It was only then that he realised he had underestimated the German raider, Emden. One more strike like that could sink his brand-new ship, part of an escort for troop transports taking Anzacs to Gallipoli.

Yet he could not work it out. Looking across the wide blue expanse of the Indian Ocean, he tried to fathom how the German shells could have reached his ship.

It was still 10,500 yards (9.6 kilometres) from Emden whose guns-he had been told-could not even reach 9500 yards (8.7 kilometres). In fact, that’s why he had planned to sail just short of 9500 yards before opening fire, believing he would still be outside the range of the Germans.

What Glossop did not know was that the Germans had cunningly modified the elevation mountings on their guns since the range data had been published, and could now fire their shells much further-as they did again and again, hitting his ship repeatedly, forcing Glossop to retreat as fast as he could.

By the time Glossop had manoeuvred his ship back out of range, however, Emden was shooting off a salvo every six seconds, and fifteen shells of the many fired had hit HMAS Sydney. These shells damaged the fore upper bridge and destroyed both vital range-finders, along with the range-finding operator and one of the guns. The shells had also started a fire among the cordite charges, which the crew had to extinguish in seconds or lose the ship.

Glossop was well aware of the responsibility resting on his shoulders as he was fighting the first battle for the Australian navy-founded just three years earlier in 1911. Nevertheless, he would have his work cut out to regain the initiative in this engagement because he had already suffered sixteen casualties and had no range-finders.

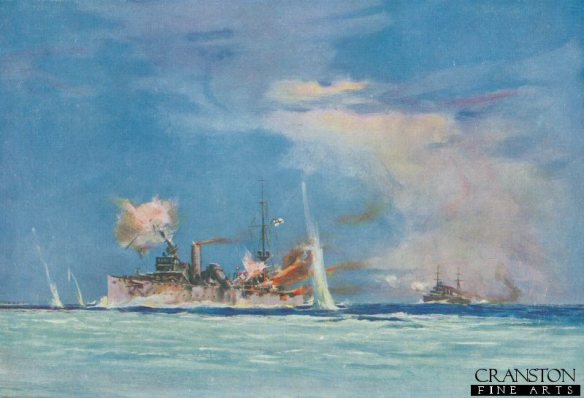

The battle

It was 9 November 1914 in the Indian Ocean, 2800 kilometres north-west of Perth, near the Cocos Keeling Islands. Captain John Glossop was trying to stop the notorious German light cruiser SMS Emden, which had destroyed a number of Allied ships in the region and was a deadly menace to troopship convoys bound for Gallipoli.

Emden had left a trail of destruction behind her-including the nearby British cable and radio station on Direction Island in the Cocos group, which was a critical component of Allied communication in and across the Indian Ocean.

As it turned out, Captain Glossop was able to pull a rabbit out of the hat because the larger HMAS Sydney (5400 tonnes) was not only faster than the light cruiser Emden (3600 tonnes) but her guns were bigger. So even without the range-finders he was confident of approaching Emden again and engaging her in battle. After all, Glossop’s ship could do 27 knots compared with Emden’s 17 and Glossop’s guns fired 6-inch shells that weighed 45 kilograms against the 17-kilogram shells from Emden’s 4.1-inch guns.

But despite the superiority of HMAS Sydney, Glossop knew that the captain of Emden, Karl von Müller, was a crafty operator. For a start, he had added a fake fourth funnel to his raider to make it look like the British cruiser HMS Yarmouth.

After being hit by Emden at 9.40 a. m., Glossop quickly sailed off to the north-east towards one of the island in the Cocos group, North Keeling Island. He was racing ahead of Emden, which was still trying to attack his ship. Glossop then positioned his ship north of Emden so that when the German cruiser caught up and was within range, Glossop was able to fire quickly at the enemy. Range-finders or no range-finders, Glossop started shelling Emden as they both sailed towards North Keeling Island on classic zigzag courses to get into striking positions, then sail away to escape being hit.

Although his gunners missed with their first salvos because they did not have the range-finders, they soon worked out how to compensate and Glossop started winning the second stage of the battle from a comfortable distance, manoeuvring much more effectively and hitting Emden with shell after shell, each doing much more damage than Emden’s shells had done before.

Glossop’s gunners pounded the smaller enemy ship for about forty minutes, hitting the Emden with at least 100 shells that completely destroyed and disabled the ship, its weapons and its crew as Emden sailed her zigzag course towards North Keeling Island.

First Glossop’s shells destroyed the voice pipes that von Müller used to give orders to the gunners, then the wireless room, the electric command transmission to the guns, the steering gear and most of the guns.

By 11 a. m. Glossop knew he had won the battle because von Müller-knowing he had lost-ran his ship aground on the reef at North Keeling Island. Emden was on fire, and steam and smoke enveloped the vessel. The German captain had no option if he wanted to save his men. Glossop’s shells had pierced his hull and the ship was sinking, and above decks the forward funnel and foremast were shot down. Most of von Müller’s crew lay dead or groaning with wounds.

After inspecting Emden later, Glossop said:

My God, what a sight! Her captain had been out of action 10 minutes after the fight started from lyddite fumes, and everyone on board was demented by shock and fumes and the roar of shells bursting among them. She was a shambles. Blood, guts, flesh and uniforms were all scattered about. One of our shells had landed behind a gun shield, and had blown the whole gun crew into one pulp. You couldn’t even tell how many men there had been. They must have had forty minutes of hell on that ship . . . and the survivors were practically madmen.

But even after running his ship aground, the determined von Müller would not give up and still insisted on flying the German flag. So Glossop signalled in the international code, `Will you surrender?’ But the Emden replied in Morse code: `What signal? No signal books’. Glossop, by now losing patience, replied, `Do you surrender? Have you received my signal?’ But as von Müller did not reply this time Glossop sent two more salvos into Emden, killing twenty more Germans, saying later he felt like a murderer having to do this to the bloody wreck with its wounded crew.

But it had the desired effect and a German sailor quickly climbed the damaged mast and pulled down the flag. At last von Müller had admitted defeat. So Glossop captured the enemy ship, taking the survivors from Emden.

Historical background

Within days of World War I starting on 4 August 1914, Australia offered troops and naval vessels to help Britain in her fight against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When the first of these troops set sail for the Middle East, bound for Egypt en route to Gallipoli, the naval vessels were assigned to escort ships transporting Australians and New Zealand troops-the Anzacs. Although the Royal Australian Navy had been established only in 1911, the new nation had taken delivery of enough British ships launched in 1913 to provide the escort. The convoy that set out from Australia included four cruisers as escorts: HMAS Melbourne, HMS Minotaur, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Ibuki (Japan being one of the Allies) and the pride of the Australian naval fleet, HMAS Sydney under Captain John Glossop, RN.

Any captain that sank Emden would have a real feather in his cap because the light cruiser had such an illustrious history. Launched in 1908, Emden became part of the German East Asia Squadron based at Tsingtao (now Qingdao) in China. After war broke out, Emden, under Korvettenkapitän (Lieutenant Commander) Karl von Müller, was sent towards the Indian Ocean to raid Allied shipping, which is when the cunning Müller put in a fake fourth funnel that made the ship look like the British cruiser HMS Yarmouth.

Emden certainly had it coming, because she had left a trail of destruction in her wake. Within three months, between August and October 1914, Emden sank or captured twenty-one merchant vessels and warships. She had also shelled and damaged British oil tanks at Madras, India, and captured the collier Buresk with her cargo intact, crewing her with German seamen to accompany Emden as a supply vessel. Emden also accounted for an obsolescent Russian heavy cruiser and a French destroyer off Malaya at the Battle of Penang on 28 October. By early November at least 60 Allied warships were hunting Emden.

But when Emden reached the Cocos Islands at 6 a. m. on 9 November to destroy the communications base on Direction Island, the Eastern Telegraph Company staff quickly realised they were under attack and sent a message saying, `Strange ship in entrance’, and `SOS, Emden here’. When a German shore party of 43 seamen under Kapitänleutnant (First Lieutenant) Hellmuth von Mücke landed with three boats to destroy the base, the civilian staff on the island offered no resistance. In return, Mücke promised not to shoot down the 54-metre radio tower onto their tennis court. Mission completed, Emden signalled the collier Buresk to join her.

Meanwhile, by lucky coincidence HMAS Sydney and the convoy were only 80 kilometres away. The Anzac convoy picked up the distress message from the communications base on Direction Island. The leader of the Anzac convoy, Captain Mortimer Silver, RN, captain of HMAS Melbourne, decided to detach Sydney in response to the SOS at 7 a. m. The commander of Ibuki pleaded to go on the mission, but Silver refused because the RAN ship was a state-of-the-art light cruiser, commissioned in 1913 and commanded by Glossop, a well-regarded Royal Navy officer.

Before long, Glossop’s smoke was seen on the horizon by lookouts on Emden, whose crew knew an unfriendly ship was on the way from intercepted radio signals. Müller had no choice but to raise anchor and engage the Australian cruiser, even though this meant he had to leave Mücke and his landing party behind.

Sydney won the engagement decisively. She was of course larger, faster and better armed-eight 6-inch guns compared with Emden’s 4.1-inch guns-so Glossop used his speed and superior guns to good effect. Glossop was cheated of a second prize, though, because when Sydney pursued Emden’s support vessel, Buresk, he found it had been scuttled.

HMAS Sydney defeated Emden decisively. Australians had proven their prowess in battle. Glossop had also demonstrated his fighting skills, recovering from the initial surprise attack through an intelligent manoeuvring and firing strategy. He also praised his young and inexperienced crew for fighting bravely: `They speedily settled down. The hail of shell which beat upon them was unceasing, but they paid as little heed to it, as if they had passed their lives under heavy fire instead of experiencing it for the first time’.

Britain’s First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill, also thought it was a great battle, sending a message soon afterwards: `Warmest congratulations on the brilliant entry of the Australian Navy into the war, and the signal service rendered to the Allied cause and to peaceful commerce by the destruction of the Emden’.

After his great victory, Glossop then collected the survivors from Emden and sailed as fast as he could for Colombo, Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), to catch up with the convoy transporting the Anzacs towards Egypt, from where they would sail to Gallipoli.

Postscript

Although it was a clear victory, the English-born Captain John Glossop was criticised for being caught by Emden’s first salvo. He nevertheless was appointed CB (Companion of the Order of the Bath) after destroying the Emden, and awarded the Japanese Order of the Rising Sun and France’s Légion d’Honneur. He was promoted Rear Admiral in 1921 and became a Vice Admiral on the retired list in 1926.

Even so Glossop was actually very lucky to get away with the mistake he made. He should not have assumed the Emden’s range was so limited and should not have taken the risk to get so close before he started firing.

He was also very lucky that the first shell that destroyed his range-finders and killed the operator did not actually explode. If it had, the damage may have been so bad it might have ended the battle right then. In fact, only five of the fifteen German shells that hit Sydney exploded.

The convoy was also lucky because the Emden could easily have intercepted one or more of the thirty-eight ships of the convoy transporting 30,000 Anzac troops.

History almost repeated itself in 1941. In World War II, HMAS Sydney’s successor met the disguised German raider Kormoran, again in the Indian Ocean. The Australian ship sailed too close again before opening fire, and the German ship again got in first with a deadly salvo. The two ships fought a fierce battle, but this time the Germans got their own back, sinking Sydney with the loss of all 645 on board. The battered Kormoran burned and sank soon after, but 317 Germans in lifeboats managed to make it to the Australian coast.

Glossop also made another mistake, for after rescuing 230 Emden survivors for transport to Colombo, he did not chase the Emden shore party on Direction Island till next morning and Mücke and his men escaped on a stolen boat.

They seized the 125-tonne three-masted schooner Ayesha, moored in the lagoon at Direction Island, and audaciously sailed it to Padang on Sumatra in the neutral territory of the Dutch East Indies. They linked up with a German merchant vessel and sailed to Turkey via the Red Sea, arriving on 5 May 1915 (just after the Anzacs escorted by HMAS Sydney had landed at Gallipoli). Mücke’s men then travelled overland to Germany and rejoined the war effort.