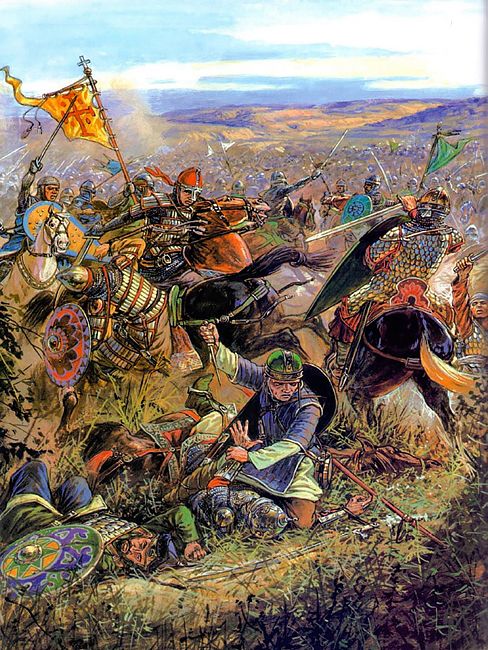

“Battle of Nicaea (1097)”, Igor Dzis

Pope Urban II’s call mobilised immense numbers of people from all social classes. The “People’s Crusade” of ordinary folk, who demonstrated their Christian fervour by massacring Jewish communities across Germany and Hungary, were slaughtered by the Seljuk Turks when they crossed the Bosphorus. The more formidable army of the princes arrived in 1097, and was given the assistance of its Byzantine hosts, after the emperor had first secured the agreement of the leaders that anywhere conquered that had once been part of the empire would be returned to Constantinople’s rule. It is impossible to know the size of this army, but it is clear that the initial force was, by the standards of the times, very large. [1]

The first objective for the crusaders was the major city of Nicaea (modern Ýznik), capital of a Seljuk principality since the Turkish victory at Manzikert in 1071. Alexius Comnenus was naturally keen to have the Latin army recapture this important place for him. The city, although important, did not have modern defences. Little had changed since the capture by an Arab army in 725, when the single, but relatively strong, late Roman curtain wall had been undermined. Since then, earthquakes had caused damage in 740 and in 1065, and more damage had been caused during a revolt in 975 (on which see below). It has to be assumed that the earthquake damage had been repaired by 1097, a likely scenario given that Nicaea had become a Seljuk capital. At nine metres in height and between three and four metres thick, the wall was as strong as anything in western Europe, although now very old, but it is not clear how substantial was the ditch in front. However, the large number of projecting towers (more than one hundred) ensured effective flanking to protect the face of the rampart.

The emperor had nearly succeeded in persuading the Turks to surrender the town to his benevolent rule rather than face the wrath of the crusaders, a course of action recommended in the face of the overwhelming strength of the besiegers. However the Seljuk sultan Kiliç (Kilij) Arslan I, who had been away fighting rivals for Melitene (Malatya), brought up a relieving army. This hardened the resolve of the garrison. However, this army was defeated in bloody battle, and the heads of the dead were propelled over the walls by catapult. Albert of Aachen said that the attackers had been there for seven weeks before the order to build siege weapons was given, others suggested (perhaps more probably) that this was done very quickly. The Christian forces were familiar with a range of equipment: reference has already been made to stone-throwing artillery, and all the sources agree that siege towers were also ordered. Count Raymond set up mangonels to bombard one tower, but “whatever the force with which the shots were directed, it was impossible to break or dislodge a single stone of the ancient edifice, provided with an almost indissoluble cement” (Albert of Aachen). Eventually, by increasing the number of machines and by dint of continuous bombardment, a few stones were dislodged. A major method of attack was the battering ram. All the versions, with the exception of an unclear reference by Anna Comnena, imply either that there was no ditch requiring to be filled up first, or at most a shallow one presenting but little obstacle, a major weakness of the defence.

The attack was pressed on all fronts, as the crusaders had assigned a portion of the wall to each of their commanders. Albert describes a machine made of oak timbers to shelter an approach to the foot of the wall, in which were twenty knights, but all were killed when it collapsed on them. The role of the siege towers at Nicaea seems to have been to provide shelter for miners to sap the foot of the wall, by clearing defenders from the immediate area. The defenders responded with inflammable mixtures, which destroyed some of the attacking machines. Raymond of St Gilles ordered the construction of a circular tower protected with leather hides outside and entwined wickerwork inside. From it, trained sappers with iron tools were to work on breaking down the Gonatas tower, so-named in Greek from its “kneeling” shape when it had been undermined and brought down in the siege of a rebel a century earlier (Anna Comnena). The anonymous describes how after several days of attack, a hole was excavated and propped up with timbers, then burnt so that the masonry collapsed. However, because the breach occurred in the middle of the night “like a crack of thunder” the crusaders were not in position to exploit it, and the Turks were able to repair the damage.

The Byzantines were close by but not taking part in the siege operations. Alexius had until recently been a sworn enemy of the Normans, whom he had every right to regard as treacherous aggressors. He had, however, maintained contact with the Turks in Nicaea. When he observed that the sultan was regularly sending assistance across the lake to the city, he ordered boats built. In order to cover his intentions, he sent a contingent of 2,000 missile troops to assist the crusaders in the next day’s planned assault on the walls, and then sent more troops against the city using the boats. The Turks accepted his generous terms of surrender and admitted his forces to Nicaea, and the next the astonished crusaders knew was the appearance of imperial standards on the walls above them.

The main defence of Nicaea had been, probably, the solidity of the walls, requiring a massive attack by sapping. Despite all their numbers and resources, which were sufficient to press the attack on all sides at once, and to build and operate as many machines as there were engineers present to oversee, the crusading army had in fact managed to breach the wall in only one place, and that without further consequence. It was clear that with the defeat of the relieving army the city’s fall was inevitable and was merely pre-empted by the emperor’s manoeuvre to make sure that it was the Byzantine standard that was raised over it. Anna Comnena suggested that Alexius believed that Nicaea would never fall to crusader assault, but this is contradicted by the speed with which the Byzantine moved to take it himself.

[1] After a careful analysis, France, Victory in the East, 141–2, concluded that the army that began the siege of Nicaea in 1097 may have been around 50,000–60,000 including non-combatants, with a core of 7,000 or more knights. The People’s Crusade is estimated at 20,000.