THE UKRAINSKA POVSTANSKA ARMIA, OR Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), was a nationalist insurgency force that waged a war of national liberation in 1942‑1949 against Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, and Communist Poland.

This force traces its beginning to 14 October 1942. At first, it consisted of only a few small, nationalist, para‑military detachments. These units quickly expanded into companies and battalions, with a centralized high command, rank structure, military awards system, publications, officer training schools, and other attributes of a regular army. Though its stated goal was a free and independent Ukrainian state, the UPA also included in its ranks military units of other captive nations (Azerbajdzanis, Uzbeks, Tatars, Georgians, and others); a high percentage of its medical doctors were Jews. According to the most conservative estimates, the UPA in 1944 had approximately 30,000 infantry soldiers, who were supported by a well‑organized, armed, nationalist civilian network and a majority of the six to seven million Ukrainians residing in the western territories of the Ukraine.

Following the 22 June 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union, most Ukrainians, especially those in the western regions, welcomed the German Army as liberators from Communist Russian control. However, the Nazi regime quickly demonstrated that the Ukraine was meant to be nothing more than a German colony.

Attempts to create an independent Ukrainian state were brutally suppressed. By September 1941, the existing nationalist network, which advocated a free Ukrainian state, was virtually destroyed, with most of its known leaders incarcerated or executed. Only a few leaders managed to evade the Gestapo and to organize an anti‑Nazi underground group.

During 1942, Nazi policies in the Ukraine became so unbearable that some Ukrainian villages began to openly resist. Another threat to the villages came from marauding bands of Soviet partisans, moving into the region from Byelorussia or by parachute. The two dangers indicated the need for self‑defense. By the end of the year, the nationalist underground provided leadership and organization necessary for the incipient insurgency in the countryside. Several military units were already in action, which were later consolidated into the UPA. These first units were initially concentrated in the forest and swamp region of northwestern Ukraine. The primary focus of the insurgency eventually shifted to the western Ukraine region of Galicia, where the forests of the Carpathian Mountains were particularly suited for guerrilla warfare and the local population had strong nationalistic feelings. This area remained a UPA stronghold.

At the end of 1943, the various insurgency areas were reorganized into three corps‑level regions under UPA headquarters: UPA-North (northwestern Ukraine), UPA‑South (central Ukraine), and UPA-West (Galicia). Each of these regions was further subdivided into military districts, whose territory was based on one of the Soviet oblasts (provinces). The largest maneuver unit in the UPA was the light infantry battalion, consisting of three to four rifle companies, each company being divided up into platoons and squads. The internal structure of the units was very flexible. The squad normally consisted of 10‑12 soldiers, but could be increased to 16 or more men. The platoon had three or four squads and the company three or four platoons. The structure of an individual unit was influenced by a number of factors: previous military experience of the unit commander, availability of qualified officers and NCOs, or a sudden influx of new volunteers. The battalions were sometimes grouped into regiments, but only for specific operations.

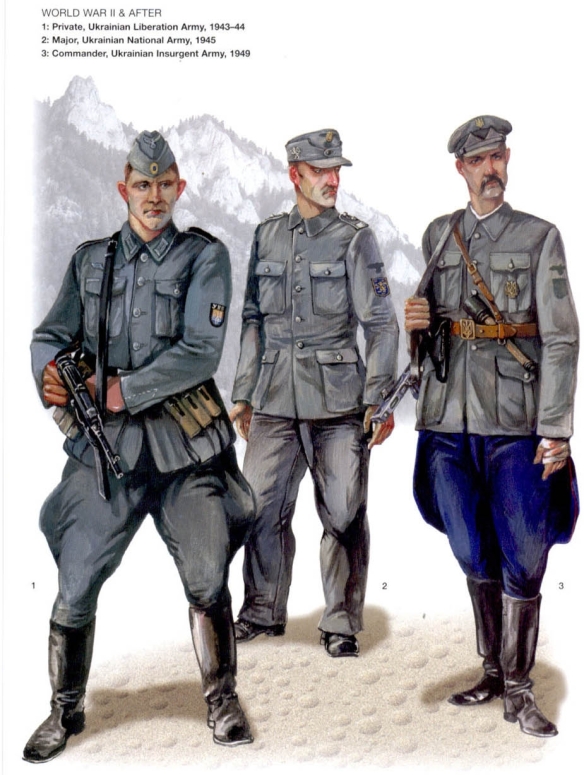

There were no headquarters or support units, as logistics were usually taken care of by the civilian network. Food was provided by the nearest village, while weapons and ammunition were captured from the enemy. UPA units were really light infantry, though during the 1943‑1944 period there were some cavalry troops and artillery batteries in UPA North. Armament of most companies also included mortars, heavy machine guns, and anti‑tank weapons. However, beginning in 1945, each unit gradually divested itself of any weapons that could not be carried by soldiers on missions. The basic complement of weapons of a UPA squad during most of the Army’s existence was usually one light machine gun, two to three light automatic weapons, and seven or more rifles. Soldiers’ clothing was mostly parts of captured enemy uniforms.

The Germans made many attempts to destroy the UPA. Most of their operations were conducted in the northwestern regions during 1943 and in the Carpathian Mountains during 1944. Despite German technical and often numerical superiority, however, most of these operations ended in failure. This can be attributed to the excellent UPA intelligence network, which allowed it to choose the time and place of most conflicts. Another reason for the lack of German success was the inferior quality of the German troops used against the UPA, consisting mostly of police and auxiliary units. The end result was that, during the final year of Nazi occupation, the Germans controlled only the cities and the major transport routes, while most of the countryside was under UPA control, especially at night.

As the Eastern Front moved westward during 1944, UPA units used various methods to cross it. Some units fought their way through German and Soviet lines, usually suffering heavy casualties. Others dispersed in their home areas on the approach of the front, bid in underground bunkers until it passed over them, and then reassembled. Still others went into deep forests or swamps and waited. After crossing the front, UPA units tried to avoid fighting with Red Army units and concentrated on the elite NKVD (Soviet security forces) units following. This policy was due to the notion that the Red Army was composed largely of conscripts (many of them ethnic Ukrainians), who at heart were also anti‑Russian and could be influenced to revolt against the Communist regime.

The Soviet security forces used various stratagems to combat the insurgency, including periodic “amnesty” proclamations for insurgents. Only one such call of amnesty was somewhat successful, in the summer of 1945, as men who had joined to evade being drafted by Nazi or Soviet forces during the war surrendered. However, the reorganized UPA was now truly a force of dedicated fighters; its small, highly mobile new units continued to control most of the countryside of the western Ukraine.

Another NKVD tactic was special long-term operations, in which security units would be stationed in each village in a large geographic area. Other security units would block all possible exits from the area, and additional units would systematically comb all forests within the encirclement. The most successful of these operations occurred during January‑April 1946, when virtually every village in the western Ukraine received a contingent of Soviet troops. Specially equipped security units searched the snow‑covered forests with the aid of aircraft and tracking dogs. The end results were that there were no safe areas and that UPA units were forced to be continuously on the move in unusually harsh winter conditions. Despite these hardships, the UPA still managed to seriously disrupt the first postwar Soviet elections in the Ukraine held on 11 February 1946.

Meanwhile, the UPA also conducted combat operations after World War II outside the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The UPA sent its units on raids into the Byelorussian SSR, Communist Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The first raid occurred at the end of the summer of 1945.

The UPA had a brigade‑sized unit of four battalions permanently stationed in Communist Poland, as the Soviet‑Polish border agreement of 1944 sliced away an elongated strip of Ukrainian ethnographic territory into Poland. The agreement had also called for an exchange of populations, with the result that 700,000 Ukrainians whose ancestral lands had become Polish territory had to move to the USSR, and their place taken by Poles migrating from the USSR. This process lasted from 1944 to 1947, due to violent resistance by UPA units. Most of the surviving UPA units crossed over into the USSR in 1947, remaining active for another year or so. One of the UPA battalions was dispatched to tell the West of anti‑Communist resistance in the Ukraine and fought its way across Communist Poland and also across Czechoslovakia. Three months later, after heavy losses in personnel, Company 95 of the UPA crossed the Iron Curtain on 11 September 1947, with remnants of other units following behind.

By the summer of 1949, there were still several cadre‑strength UPA companies in the Carpathian Mountains. One of these conducted a daring raid into Rumania, which lasted five weeks. Finally, on 3 September 1949, Brig. Gen. Roman Shuchewycz, UPA commander since 1943, inactivated the remaining units and transferred their cadre underground. Thus closed the final chapter of the UPA, whose surviving soldiers continued to fight within another organizational framework until about 1956. They were able to wage a long‑term and seemingly hopeless struggle against a major world power only because the Ukrainian people identified with the UPA and provided it with the necessary support.