The second phase of the western campaign, which began on June 5th, 1940, and ended less than three weeks later with an armistice between France, Germany and Italy, saw the Luftwaffe, on the model of the Polish campaign, mainly occupied in giving close support to the rapidly advancing army. Its next opponent would be Britain. Or would that country prefer to be “reasonable” and come to terms before the struggle re-opened and the island bore the whole brunt of the enemy’s might?

On July 10th south-east England and the Straits of Dover lay covered beneath broken cloud, height about 6,000 feet, with short, sharp showers beating down. A low-pressure front was approaching from the North Atlantic, and over the rest of England it was raining cats and dogs. The weather was typical of this very wet July.

The German fighter pilots, whose units had gradually re-grouped on airfields behind the Channel coast, slapped their arms about to keep warm. Mud stuck to their flying boots, and the runways had become swamps. How were they supposed to force the British fighters into battle under such conditions? Or was there to be no battle after all?

No one seemed to know. Since the end of the French campaign most of them had been cooling their heels, while the Luftwaffe waited and watched. The authorities hoped that Britain would take steps to end the war. For bombers and fighters alike it was a time of rest.

But there were exceptions. Today reconnaissance reported at noon a large British coastal convoy off Folkestone headed for Dover. At the command post of the “Channel zone bomber-commander”, Colonel Johannes Fink—it consisted of a converted omnibus stationed on Cap Gris Nez just behind the memorial to the British landing in 1914—the telephone rang. A Gruppe of Do 17s was duly alerted, plus another of Me 109s to act as escort, and a third of Me 110s.

Fink’s mandate was “To close the Channel to enemy shipping”. It looked as if the convoy was in for a hard time.

At 13.30 British Summer Time, several radar stations plotted on their screens a suspicious aircraft formation assembling over the Calais area. They were right, for at this moment—14.30 continental time—II/KG 2 under Major Adolf Fuchs, from Arras, was making rendezvous with III/JG 51 under Captain Hannes Trautloft, which had just taken off from St. Omer.

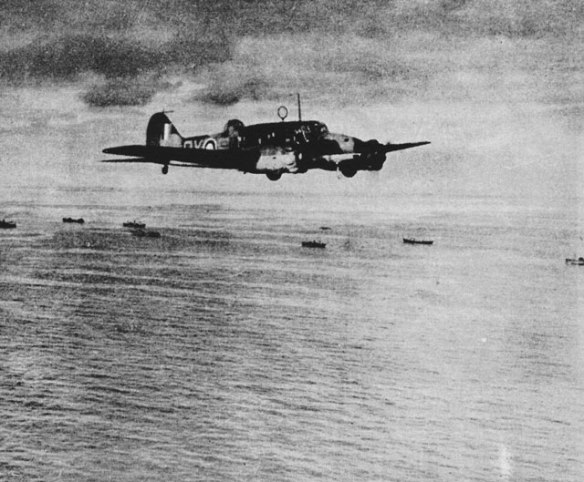

One fighter squadron took over close escort of the Dorniers, while Trautloft went up with the other two to between 3,000 and 6,000 feet to be in a favourable position to attack any enemy fighters that assailed the bombers. The stepped-up formations then made a bee-line towards the English coast- some twenty Do 17s and twenty Me 109s. Within a few minutes they sighted the convoy.

Approaching from another direction were the thirty Me 110Cs of ZG 26 under Lieutenant-Colonel Huth, making a total of seventy German aircraft. Would the British accept the challenge?

Routine air cover for a British convoy consisted of just one flight of fighters’—in this case represented by six Hurricanes of 32 Squadron from Biggin Hill. According to British sources these six had the additional disadvantage, just before the crucial attack, of becoming split up in a rain cloud. When the first section of three eventually emerged, they were startled at the sight of “waves of enemy bombers approaching from France”. Undeterred, “the Hurricanes pounced on them—three versus a hundred”, as one British report read.

In the official history of the Royal Air Force it is stated regarding these air battles of July 1940 : “Over and over again a mere handful of Spitfires and Hurricanes found themselves fighting desperately with formations of a hundred or more German aircraft.”

Against such evidence stands the fact that during this period the only fighter unit facing England across the Straits of Dover was JG 51, under the command of Colonel Theo Osterkamp. Thanks to the bad weather and the air battles in which they were engaged, the aircraft serviceability of his three Gruppen—under Captains Brustellin, Matthes and Trautloft—declined to such a degree that he had to be reinforced on July 12th by a fourth one (III/JG 3 under Captain Kienitz) to retain his operational strength of sixty/seventy Me 109s. Such a modest force had furthermore to operate with considerable discretion if its strength was not to be dissipated before the real assault on Britain began. It was not until the last week of July that JG 26 (of which Captain Galland led a Gruppe) and JG 52 began to take part in the Channel battle.

But back to July 10th—the date on which the Battle of Britain is regarded as having begun. The Dorniers of III/KG 2 were approaching the convoy when Captain Trautloft suddenly sighted the patrolling Hurricanes flying high above: first three, then all six of them. For the moment the latter made no attempt to interfere, but held their altitude waiting for a chance to elude the twenty German fighters and attack the bombers below them. In this way they were more of a nuisance than if they had rushed blindly to their own destruction.

Trautloft was compelled to remain constantly on watch. To engage them or just to chase them off would take his force miles away from the Dorniers, which he was committed to protect and bring safely back home. That might be exactly the Hurricanes’ intention: to entice the Me 109s away by offering the hope of an easy victory so that other fighters could attack the bombers without hindrance.

Within a few minutes the Dorniers had penetrated the ships’ flak zone, unloaded their bombs over the convoy, and dived to sea level for the return journey. But in these few minutes the whole situation changed.

Warned in good time by the radar plots, the R.A.F.’s 11 Group threw into the battle four further squadrons of fighters : No. 56 from Mansion, No. 111 from Croydon, No. 64 from Kenley and No. 74 from Hornchurch. The first two were equipped with Hurricanes, the second two with Spitfires.

“Suddenly the sky was full of British fighters,” wrote Trautloft that evening in his diary. “Today we were going to be in for a tough time.”

The odds were now thirty-two British fighters against twenty German, and there would be no more question of the former holding back. Strictly the Me 110 Gruppe should be added to the German total, but as soon as the Spitfires and Hurricanes swept on to the scene from all sides, all thirty of them went into a defensive circle. With their single backward-firing 7.9-mm machine-guns, fired by the observers, they had little protection against attack from astern by faster fighters.

Accordingly they now all went round and round like circus horses in the ring, each protecting the rear of the one in front with its forward armament of four machine-guns and two 20-mm cannon. But that was all they did protect. As long-range fighters they were supposed to protect the bombers. Now, however, they just maintained their magic circle and made no contribution to the outcome.

Consequently Trautloft’s Gruppe bore the brunt of the battle, which promptly resolved itself into a series of individual dog-fights. The radios became alive with excited exclamations.

A number of Hurricanes suddenly swept from 15,000 feet in a breath- taking dive. Had they “had it”, or were they just trying to get away? Or was their objective the bombers headed homewards just above the sea?

Hard on the heels of one of them was First-Lieutenant Walter Oesau, leader of 7 Squadron and to date one of Germany’s most successful fighter pilots. The British pilot had little chance of escape, for in a steep dive the Me 109 was considerably faster. Oesau had already shot down two of his opponents into the sea, and was on the point of scoring a “hat trick” when the Hurricane ended its dive by crashing full tilt into a German twin-engined plane. There was an almighty flash as they both exploded, then the wreckage spun burning into the water. Was it a Do 17 or a Me 110? Oesau could no longer recognise the wreckage as he pulled out over it and climbed up to rejoin his comrades.

In the heat of battle Trautloft himself saw several aircraft dive, trailing thick smoke, without being able to tell whether they were friend or foe. But once, on the radio, there came the familiar voice of his No. 2 Flight-Sergeant Dau, calling urgently: “I am hit—must force-land.”

Trautloft promptly detailed an escort to protect his tail so that he would reach the French coast unmolested—if he could get that far.

Dau, after shooting down a Spitfire, had seen a Hurricane turn in towards him. It then came straight at him, head-on and at the same height. Neither of them budged an inch, both fired their guns at the same instant, then missed a collision by a hair’s breath. But while the German’s fire was too low, that of the British pilot (A. G. Page of 56 Squadron) connected. Dau felt his aircraft shaken by violent thuds. It had been hit in the engine and radiator, and he saw a piece of one wing come off. At once his engine started to seize up, emitting a white plume of steaming glycol.

“The coolant temperature rose quickly to 120 degrees,” he reported. “The whole cockpit stank of burnt insulation. But I managed to stretch my glide to the coast, then made a belly-landing close to Boulogne. As I jumped out the machine was on fire, and within seconds ammunition and fuel went up with a bang.”

Another of Trautloft’s Me 109s made a similar belly-landing near Calais, its pilot, Sergeant Küll, likewise escaping with only a shaking-up. Those were the only aircraft that IH/JG 51 lost, with all their pilots safe. Against this they claimed six of the enemy destroyed.

So it went on from day to day, with a fraction of the Luftwaffe waging a kind of free-lance war against England with a very limited mandate. With the small forces at his disposal—KG 2’s bombers, two Stuka Gruppen and his fighters of JG 51—Colonel Fink was only permitted to attack shipping in the Channel.

Towards the end of July Colonel Osterkamp paraded all his JG 51 Gruppen on a series of high-altitude sweeps over south-east England. But Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, chief of British Fighter Command, saw no reason to accept the challenge. After the heavy losses incurred in the French campaign and at Dunkirk, he was grateful for every day and week of grace to repair his force’s striking power. For one thing was certain: the Germans would come, and the later they launched their attack, the better. That would be the time to send up his squadrons against them; not now, in answer to mere pin-pricks.

“Why doesn’t he let us have a go?” murmured his pilots, to whom these sweeps were a provocation. But Dowding was adamant. The German radio interception service reported that British squadrons were being repeatedly instructed by ground control to refuse battle whenever an enemy formation was identified as fighters only. “Bandits at 15,000 feet over North Foreland flying up Thames estuary,” they would be warned. Then: “Return to base—do not engage.”

At first Dowding even refused to provide fighter cover for the coastal convoys, their protection in his view being a matter for the Navy. On July 4th, however, Atlantic convoy OA 178 had been dive-bombed off Portland by two Gruppen of StG 2, and with only the ships’ guns to defend it had suffered the loss of four vessels totalling 15,856 tons, including the 5,582-ton auxiliary flak ship Foyle Bank, with nine other vessels totalling 40,236 tons damaged, some of them badly. Thereupon Churchill issued direct orders that in future all convoys were to be given a standing patrol of six fighters. These were reinforced as soon as a German formation was reported approaching.

The periphery combats that ensued have been called by historians the “contact phase” of the Battle of Britain, with the conflict proper still ahead. With nine-tenths of the Luftwaffe resting on the ground, the few aircrews operating constantly asked themselves what the object of their exercise was. Were they supposed to knock out England by themselves?

Why did the Luftwaffe not strike in full force while Britain lay paralysed after Dunkirk, and why was it virtually still grounded even three weeks later when France had been prostrated? The answer, in retrospect, has been that after the wear and tear of the “blitz” campaign against the West, its units were in urgent need of rest. They had to recoup their strength and move forward to new bases. Supply lines had to be organised and a whole lot of new machinery set in motion before the Luftwaffe could launch a heavy assault on Britain with any prospect of success.