One secrets of Octavian’s success was his ability to delegate authority, and he had an outstandingly efficient officer in the person of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, who had been his comrade as a young man, while training in Illyricum. Agrippa, who had rendered distinguished service in Gaul and contributed to the defeat of Lucius Antonius at Perusia, now proved himself as able on sea as on land. Though Octavian suffered another naval defeat near Tauromenium (Taormina), Agrippa overcame Sextus’ fleet at Mylae. This was followed by another victory at Naulochus, which proved decisive. Octavian, by land operations, with the help of Lepidus, had already deprived the enemy of supply centres in Sicily. Sextus fled to Asia, where he was eventually captured and executed at Antony’s orders.

Agrippa was noticeably alert to the possibilities of technical innovation. In order to create a suitable naval base for war on Sextus Pompeius, he had cut a canal through the narrow strand which carried the Herculean Way between Baiae and Puteoli, thus linking the inland Lucrine lagoon(Iacus Lucrinus) with the Bay of Naples. A second canal connected the Lucrine waters with those of Lake Avernus beyond. The combined basins provided a training area in which Octavian’s fleet could carry out manoeuvres and tactical exercises whenever they desired.

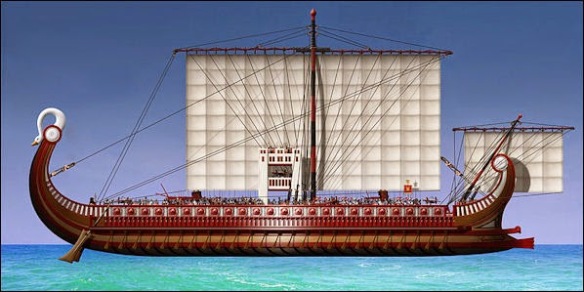

Sextus Pompeius’ success had, throughout this war in Sicilian and southern Italian waters, been dependent very largely on his use of war galleys which were lighter and smaller than those manned by his enemies. As in Cassius’ attack on Rhodes, we find evidence that the lighter galley was returning to favour and that the tactics of manoeuvre and ramming were being reintroduced against the heavier ships which provided a basis for grappling and boarding. Strategically, the light ship, with its vulnerability to wind and weather was at a disadvantage. But in localized inshore operations, it often proved its tactical value. Where fighting took place in a choppy sea, the light ship could ride the waves and was more flexible in manoeuvre. Sextus had demonstrated this even before Philippi. If by misadventure his vessels were grappled by the enemy, the crews abandoned ship at once by flinging themselves into the water. They were then picked up by friendly lifeboats, which followed the battle collecting anyone who had abandoned ship.

Admittedly, Agrippa used a new type of harpoon (the harpago) which made it easier to grapple the elusive Pompeians, but it is also apparent that he himself was in part a convert to the tactics of manoeuvre and ramming.

The Decision at Actium

The inevitable war was destined to be fought at sea, because Cleopatra wished it so. Antony seems to have been, as Octavian proclaimed, a slave to her wishes, and the sea at any rate offered the best prospect of speedy flight in the event of defeat. The armed conflict was preceded by dramatic challenges which emphasize the personal nature of warfare at this epoch. Octavian offered Antony a beachhead in Italy, with space for a camp, in order that a pitched battle might be fought there. Antony replied first with an invitation to single combat, then to a pitched battle at Pharsalus on the site of Julius Caesar’s victory. Both these offers were refused by Octavian. He had accepted a similar challenge, defining time and place, from Sextus Pompeius five years earlier and had won the decisive battle which followed. But his fleet now consisted largely of light ships, which he was perhaps reluctant to expose to the hazards of the open sea. In any case, he probably crossed in summer when the weather and the sea conditions were favourable, at a time of his choosing.

It is even possible that Octavian’s hesitance to fight in Greece was feigned and that he hoped merely to throw the enemy off his guard. Antony, poised against Italy, with sea and land forces at Actium on the Ambracian Gulf in North Greece, was certainly taken by surprise when Octavian’s armada arrived on the coast of Epirus, not far north of his own position. He was in every sense unprepared. His fleet was not yet manned. As a desperate ruse, he drew his ships up in line of battle and put out the oars, even where there were no rowers to work them. This bluff was effective and Octavian temporarily withdrew.

However, in the strategic manoeuvring and land skirmishing that followed, Antony was unable to shift the enemy from his position, while Octavian’s fleet, under Agrippa, gained important vantage points among the Ionian islands and in the Gulf of Corinth, thus cutting off Antony from his sources of supply in the Peloponnese. Morale among his officers and eastern allies had deteriorated, and among influential deserters to the enemy was Domitius Ahenobarbus, the son of Julius Caesar’s officer. But even when the decisive naval battle was imminent, Antony maintained a defensive posture, from which he was drawn only by the threat of encirclement.

Tactics, as well as strategy, reflected a trial of strength between light and heavy ships. Octavian’s slender vessels (liburnae, as they were called) were able to manoeuvre in groups of three or four around single galleys of Antony’s ponderous fleet, exchanging missiles with them; although fear of being grappled and boarded by the swarms of marines which these leviathans carried deterred them from coming too close. In such circumstances, as one might expect, a decision was not quickly reached. But while Antony’s flagship on the right was engaged against Agrippa’s squadron, his own centre and left began a mysterious withdrawal. Cleopatra’s loss of nerve has been blamed by historians. Her contingent had been anchored in the rear, laden with the treasure on which Antony’s war economy largely depended. The Egyptian squadron, taking advantage of a sudden favourable wind, hoisted sail and deserted the scene of the battle. Whatever motives underlay events, Antony certainly followed his mistress in her flight. Most of his fleet, left at the enemy’s mercy, in a state of leaderless confusion, was destroyed.

When Octavian invaded Egypt during the following year, Antony and Cleopatra had no prospect of defending themselves. Antony, abandoned by his officers and troops, committed suicide. Cleopatra was captured by Octavian, but contrived to kill herself before she could adorn the conqueror’s triumph.