Following the terrorist attacks on New York City and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, the United States launched itself into a war on terror. Any nation which participated in terrorism or gave aid to terrorists would face retribution. As the United States began confronting this terrorist threat, it became cognizant that involvement in overseas operations would be necessary. First, American and allied forces invaded Afghanistan and overthrew the oppressive, ultraconservative Muslim Taliban government, which harbored Al-Qaeda terrorist training camps and leaders like Osama bin Laden. The next move in the war on terror was against Iraq, which was known to have ties to international terrorist organizations and to harbor terrorists. Further, it was widely reported that the regime of Saddam Hussein had been developing chemical, biological, and perhaps nuclear weapons.

With the assistance of the United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency, inspectors went into Iraq to search for weapons 176 of mass destruction. For months, the Hussein regime played a game of cat-and-mouse with inspectors, giving the very strong impression that it had something to hide. However, only indirect evidence could be discovered. Without concrete confirmation, the United Nations Security Council would not sanction military operations. France and Germany led European critics of any Western military intervention. It has been suspected that illicit trade from those countries had been rampant during the United Nations embargo imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War. Receiving neither approval nor assistance from the United Nations, the United States began building a coalition force to invade Iraq. The stated goal was to make the region (and perhaps the world) safe from weapons of mass destruction in the hands of Saddam Hussein, who had already used poison gas in contravention of international agreements during his war against Iran in the 1980s. Further, Iraq’s ties to terrorism allowed for the possibility of such weapons being used anywhere in the world, as Al-Qaeda had already shown in their willingness on 9/11 to mass-murder innocents.

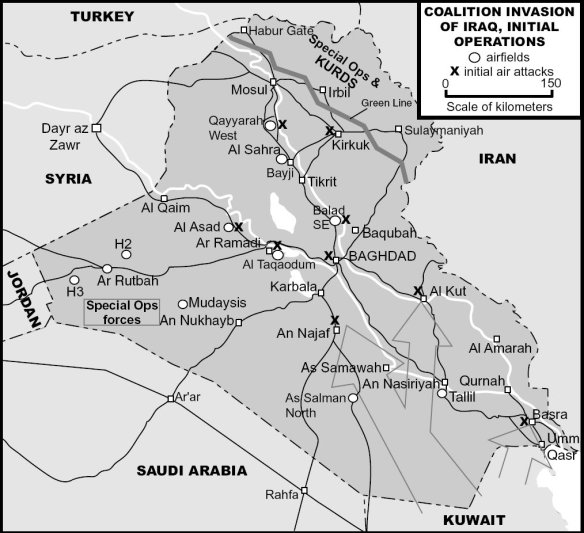

American President George W. Bush’s first action was to deliver an ultimatum to Saddam Hussein. He was given the opportunity to leave Iraq, along with his two sons Uday and Qusay, or the United States and its allies were prepared to take offensive action against the country. Meanwhile, America had been gathering allies for the operation, primarily Britain, Australia, Poland, Italy, and Spain, which came to be called the “Coalition of the Willing.” They assembled troops along the Iraqi border in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. American troops numbered 100,000 and the British contingent was 45,000. They would later be bolstered by an additional 50,000 Kurds, the population of northern Iraq that had long been persecuted by Hussein but had enjoyed something of a political resurgence in the post-Gulf War era. The United States requested permission to base troops in Turkey, but that was denied by the Turkish government, which hesitated to fight a fellow Muslim nation. Eventually, however, Turkey did allow free use of its airspace for launching attacks and delivering supplies and personnel into northern Iraq.

U.S. forces called the invasion Operation Iraqi Freedom; to the British it was Operation Telic, and to the Australians it was Operation Falconer. The invasion began around 05:30 Baghdad time on March 20, 2003, some 90 minutes after the passing of the deadline for Hussein to resign. The initial invasion troops were of the Australian Special Air Service which crossed over into southern Iraq from Kuwait. At 22:15 Eastern Standard Time in Washington, D.C., President Bush declared that he had ordered coalition troops to launch an “attack of opportunity” against significant targets in Iraq. The plan deemed most promising by U.S. commanders was a continuation of the “shock and awe” strategy originally developed in Afghanistan. According to this strategy, coalition forces would use superior mobility, firepower, and speed to overcome Iraqi defenses before they could be brought to bear against an invasion force. It was hoped that this mobility and coordination would lead to a rapid collapse of the Iraqi command structure and, thus, a victory with minimum casualties. The plan also resembled the “island-hopping” strategy of World War II in that coalition forces avoided major troop concentrations in large cities. This limited major combat saved many lives that would have been lost in house-to-house fighting. Commanders also hoped they would gain local support once the leadership of the army and government had fallen.

As coalition troops advanced deeper into the heart of Iraq, one of their objectives was to secure the country’s oil infrastructure. The oil was considered a vital objective for strategic as well as economic reasons. On March 20, troops of the British Royal Marines 3 Commando Brigade launched an evening air and amphibious assault against the Al-Faw peninsula to secure the oil facilities there. Frigates of the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy supported the operation. As this was taking place, the British Fifteenth Marine Expeditionary Unit took the port of Umm Qasr, while the Sixteenth Air Assault Brigade secured the area’s oil fields. Once Umm Qasr was secured, it was opened to shipping that brought in more troops as well as humanitarian aid for the local population.

As British troops fought for control of southern Iraq’s oil supply, the American Third Infantry Division moved northward through the desert toward the capital city of Baghdad. The U.S. First Marine Expeditionary Force and British First Armoured Division slogged through thick marshland that considerably slowed their progress. At this point, it became impossible to avoid entering the cities any longer, as it was necessary to capture strategic bridges over the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In the largest tank battle fought by British troops since World War II, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards knocked out 14 Iraqi tanks on 27 March. On April 6, the British Seventh Armoured Brigade (the famed “Desert Rats” of World War II) entered Iraq’s second-largest city, Basra, where they encountered heavy resistance from Iraqi army forces and irregulars called fedayeen. On April 9, lead elements of the British First Armoured Division linked up with U.S. forces around Al Amarah.

At this point, with the imminent collapse of the Iraqi government, electrical and water shortages became a major problem for coalition troops, as did the start of looting and other civil disturbances. The coalition soldiers found themselves playing the role of police while trying to maintain order and distribute humanitarian aid. Once U.S. troops reached the area around Hillah and Karbala, the offensive came to a temporary halt owing to heavy resistance and blinding sandstorms. The troops rested for several days and, after resupplying, were able to continue the attack.

Operation Iraqi Freedom also employed Special Forces troops in wider roles and in larger numbers than they had been since the Vietnam War. The Soldiers of Special Operations Command (SOCOM) were vital to the success of the invasion and occupation of Iraq. The Second Battalion Fifth Special Forces Group (the Green Berets) conducted reconnaissance and raids throughout southern Iraq, as well as providing support for conventional invasion forces. In northern Iraq, elements of the Tenth SFG aided Kurdish militia factions such as the Union of Kurdistan and the Democratic Party of Kurdistan. After heavy fighting in the north, Special Forces troops and their Kurdish allies were able to rout the Thirteenth Iraqi Armored and Infantry Division. The American 173rd Airborne Brigade parachuted into H3, an Iraqi airfield, and secured it for coalition use.

Three weeks into the invasion, U.S. forces entered the streets of Baghdad. The original plan to capture the city had been to surround it with armored forces and have airborne troops move in and engage in street fighting. The plan was changed, however, in favor of a “thunder run” of about 30 M1 Abrams main battle tanks through the city streets. The tanks met some resistance, including suicide attacks. Another such assault took place two days later and succeeded in capturing Saddam Hussein’s palace. On April 9, Baghdad was declared “secured” and the Hussein regime officially ended. Difficult fighting continued for a few weeks in Basra and An Nasiriyeh.

Although the bulk of the Iraqi army was defeated, some isolated units held out and, worse for the allies, guerrillas began operating in both cities and the countryside, while looting became so widespread that little could be done to stop it. Not only were government offices looted by those who had been terrorized by them for so long, but those with a more professional eye soon removed many treasures from the National Museum of Iraq. So many buildings and facilities had to be protected that not everything could be watched. Many believe that the best pieces were taken by members of the Hussein regime before the city fell.

On May 1, 2003, President Bush declared major combat operations to be at an end. On May 22, 2003, the United Nations voted to end the embargo against Iraq and support the U.S.-led government that was being planned. As far as the Iraqi field forces were concerned, the war was indeed over, but thousands of die-hard Hussein supporters as well as terrorists from outside Iraq began a classic urban guerrilla war. Areas dominated by Sunnis (the minority group that had dominated the government) were bases for rocket and mortar attacks, as well as sniping and the new weapon of choice, hidden roadside bombs called improvised explosive devices, or IEDs. Although those leading the war called for expulsion of the infidels occupying their country, the bulk of the population of the Shia faith were more than happy to see Hussein and his cronies removed and grateful to the soldiers who made it happen. As the guerrillas began to find that they received far greater casualties than they inflicted when fighting coalition troops, they altered their targets to Shia civilians in hopes of provoking a religious civil war. Although tensions remained high between Sunni and Shia factions, no mass uprising took place.

Unfortunately that was followed by Hell in Iraq!