Operation Bolo was a famous air battle fought in the skies of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on January 2, 1967, during the Vietnam War, and in the context of the United States Air Force’s Operation Rolling Thunder aerial bombardment campaign. Bolo pitted the new American F-4 Phantom II multirole fighter against its rival, the Soviet Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 interceptor. Operation Bolo, considered to be one of the most successful combat ruses of all time, prompted North Vietnamese pilots and strategists, as well as Soviet tacticians, to reevaluate their employment of the MiG-21.

The bombing of the North continued, with only a few pauses, from spring 1965 to the eve of the 1968 US presidential election. During the war the United States and its allies would drop nearly 8 million tons of bombs on Indo-China (6,162,000 tons by the US Air Force). This is more than twice the tonnage dropped by the Allied powers in all of World War II. Most of it fell in Laos and South Vietnam.

The air war against the North was actually separate from the war in the South, in that it was controlled by Washington rather than MACV. Although commander of US forces in the Pacific (CINCPAC) Admiral Ulysses Grant Sharp in Honolulu had operational command, Washington determined the targets to be struck. In the air war, as on the ground, gradual escalation was the operational mode. Ostensibly a military operation, the air war over the North was in reality a political tool, designed to force the DRV to give up its support of the insurgency in the South. Its goals were to halt infiltration and bring North Vietnam to the bargaining table.

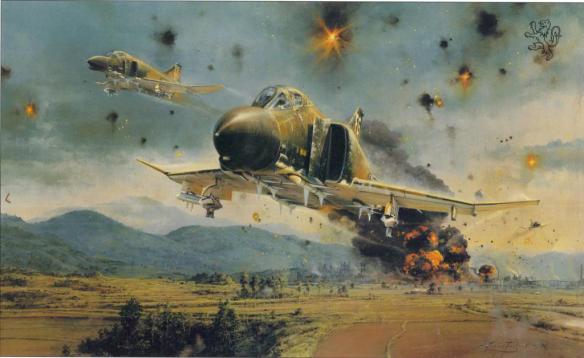

Fighter-bombers and interceptor aircraft rather than strategic bombers carried the bulk of the war over the North. Operation Rolling Thunder consisted of some 304,000 sorties, but only 2,380 were by B-52s. The Air Force relied chiefly on the F-105 Thunderchief and F-4 Phantom. The F-105 flew more than 75 per cent of all Rolling Thunder strike sorties. At more than 50,000 pounds fully loaded, the “Thud” had difficulty turning in dogfights but still accounted for more MiG kills than any other US aircraft save the F-4. The F-4 Phantom may have been the best multi-role aircraft ever built, although the tell-tale black smoke from its engine made it an easy target for air defenses. Flown by the Air Force, Navy and Marines, the F-4 shot down 55 MiGs (18 MiG-21s), more than any other aircraft. The A-4 Skyhawk, a small single-seat fighter capable of carrying 4 tons of bombs, flew more bombing missions than any other Navy aircraft in Vietnam. There were also the Navy and Marine allweather capable A-6 Intruder and the Air Force F-111 (Aardvark).

Rolling Thunder underwent the same gradual escalation as the ground war. At the beginning of the bombing campaign Hà Nôi had no jet aircraft, no missiles, fewer than 20 radar installations and only a few obsolete antiaircraft guns. But within two years thanks to support from the USSR the DRV boasted the most sophisticated air defense system in the world. Colonel Jack Broughton, Deputy Commander of the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, described North Vietnam “as the center of hell with Hanoi as its hub”.

On 24 July Russian surface-to-air missiles (SAMS) claimed their first victim, an F-4C. By the end of the year there were 60 SAM sites in North Vietnam. Also that year the DRV obtained MiG-15 and MiG-17 aircraft. On 3–5 April 1965, US aircraft struck rail lines to Hà Nôi, the furthest penetration north to that time. Six US aircraft were lost, including one downed by MiGs in the first air-to-air combat of the war.

North Vietnam’s air defence system grew dramatically. By the end of 1966 the DRV had some 150 SAM sites and 70 MiG interceptors; over 100 radar sites provided early warning and tracking for some 5,000 anti-aircraft guns. During 1967 SAM sites increased to some 250. That year there were also 7,000 anti-aircraft guns and 80 MiG fighters, ranging from the MiG-15 to the advanced MiG-21. The number of SAM firings illustrate this growth. In 1965 a total of 194 SAMS were fired, but over the next year 990 were launched, followed by 3,484 in 1967.

Against these defences Admiral Sharp committed the most sophisticated aircraft and weaponry in the US inventory. In 1967 the US first used the Walleye “smart bomb”, a 1,000 lb bomb locked onto a target by a TV eye. US fliers also developed technological countermeasures to deal with MiG and SAM threats. They were slower to develop air tactics for dealing with North Vietnamese pilots, abetted by problems with inaccurate air-to-air missiles. In late 1967, in a stunning turn of events, DRV pilots began shooting down more US aircraft than they were losing. The Air Force largely ignored problems with its tactics, formations and missiles, but the Navy undertook a complete reassessment of its air-to-air operations and in 1969 established its Top Gun training course for pilots. Thereafter it enjoyed a 12-to-1 kill ratio.

Despite SAMS and MiG interceptors, guns remained the most deadly threat to attacking aircraft. Of 3,000 US aircraft lost during the Vietnam War, some 85 per cent were downed by guns. Missiles accounted for only 8 per cent; less than 2 per cent of some 9,000 SAMS fired at US aircraft reached their targets. MiG kills amounted to 7 per cent. In the air war over North Vietnam the United States lost nearly 1,000 aircraft, hundreds of men taken prisoner, and hundreds more killed or missing in action.

Washington steadily escalated the bombing of the North from more than 10,000 sorties a month in 1966 to more than 13,000 a month in 1967. Bombs struck thousands of fixed targets, many more than once, and thousands more moving targets. By the end of Rolling Thunder the US had dropped more than a million tons of bombs on North Vietnam. This cost the DRV more than half its bridges, virtually all of its large petroleum storage facilities, and nearly two-thirds of its power generating plants. It also killed some 52,000 people. US pilots could, and often did, drop more bombs in one day than the French had been able to deliver during the entire siege of Ðiên Biên Phu, but the bombing did not bring Hà Nôi to the negotiating table. Undoubtedly it strengthened US and South Vietnamese morale and made the war much more costly for the DRV, both in terms of lives lost and matériel. It also forced the diversion of labour from farming and other pursuits to repair bomb damage and man air defences.

Throughout Rolling Thunder the Air Force searched for a magic technological bullet to win the war, without success. Earl Tilford has noted:

Cluster bombs, napalm, herbicide defoliants, sensors dropped along the Ho Chi Minh Trail to monitor traffic and aid in targeting, gunships, and electro-optically guided and laser-guided bombs all promised much, and while some delivered a great deal of destruction, in the end technologically sophisticated weapons proved no substitute for strategy.

Operation Rolling Thunder was a failure. Supplies still reached the South at a level sufficient to sustain DRV/VC military operations, especially as they required only a small fraction of that necessary to sustain US/RVN forces. One estimate held that 10 to 20 truckoads of supplies a week supplemented by porters would maintain the insurgency, and there was no way the bombing could prevent that amount from getting through. Also, despite pauses in the bombing, Hà Nôi showed no inclination to end its support for the war. If anything, the bombing intensified Hà Nôi’s determination and solidified popular support in the DRV for the war effort.

While not as dramatic as the air war over North Vietnam nor as costly in terms of casualties as the ground war in the South, the war at sea was important, and the US Navy played a large role in it. The Navy had found itself largely unprepared for Vietnam. Long geared to nuclear war, it had neglected shore bombardment and amphibious assault. After the Tonkin Gulf incidents the Navy instituted frequent gunnery exercises and extended the service life and returned from mothballs several gun cruisers and the battleship New Jersey. New aircraft such as the RA-5C and the A-6 Intruder aided reconnaissance and strike capabilities, and Shrike missiles allowed aircraft to hit North Vietnamese anti-aircraft radars.

The most visible US Navy role was in Seventh Fleet carrier operations. Carrier aircraft participated in Rolling Thunder and also provided support to ground forces in South Vietnam, and on occasion in Laos and Cambodia. Surface warships gave fire support to friendly troops ashore. In Operation Sea Dragon the Navy mounted harassment and interdiction raids along the North Vietnamese coastline. Another important mission was halting infiltration by sea from the North. Market Time patrols, begun in 1965, involved long-range aircraft, medium-sized surface ships, and fast patrol craft known as “swift boats”.

In the Mekong delta a “brown-water fleet” came into being, consisting of fibreglass patrol boats, shallow-draft landing craft, and fire-support monitors. US Navy unconventional warfare teams known as SEALS (Sea-Air- Land) and Navy helicopter units searched out VC/PAVN troops far from the sea; and Navy river convoys resupplied the Army and Marines inland. On several occasions, the Navy also put Marines ashore in amphibious assaults.