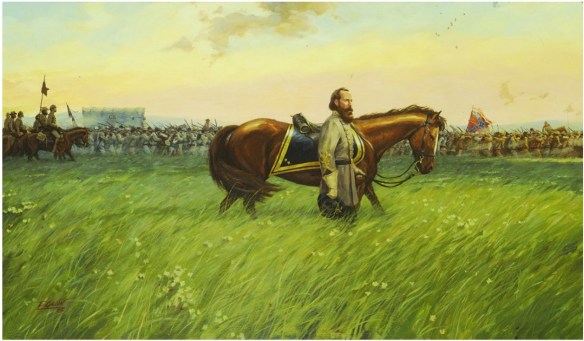

Lt. General James Longstreet and his beloved First Corps, marching to Gettysburg.

Seen and heard on the road to Gettysburg—At the Potomac River on June 23, 1863, Colonel Abner Perrin of the 14th South Carolina Infantry Regiment: “I do not suppose that any army ever marched into an enemies’ [sic] country with greater confidence in its ability…and with more reasonable grounds for that confidence.” Likewise, British Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Freemantle, a friendly, self-appointed observer traveling with Robert E. Lee’s northbound columns, was moved to call the troops marching before him “a remarkably fine body of men…[who] looked quite seasoned and ready for any work.”

The next day, on the Maryland side of the Potomac, a famous Confederate threesome gathered at Robert E. Lee’s tent for a conference: Lee himself and A. P. Hill and James Longstreet, his two corps commanders. In came a youngster named Leighton Parks, an acquaintance from Lee’s invasion of Maryland the previous year. The small boy appeared this time with a bucket of raspberries for Lee, who picked him up, kissed him, and invited him to stay for lunch. The child then took turns on the great commander’s knee, on Longstreet’s knee, and on a horse ordered forward by A. P. Hill.

Soon after, Lee’s march northward resumed.

Seen and heard on the road to Gettysburg as the Maryland countryside fell behind—British observer Freemantle on the Pennsylvania Dutch: “They are the most unpatriotic people I ever saw, and openly state that they don’t care which side wins, provided they are left alone. They abuse Lincoln tremendously.”

Confederate division commander Dorsey Pender, in a letter to his wife on June 28: “I never saw troops march as ours do; they will go 15 or 20 miles a day without leaving a straggler and hoop and yell on all occasions.”

Also seen and heard—Cincinnati Gazette reporter Whitelaw Reid wrote that the Union Army “had done surprisingly little damage to property along their route.” Breaking off the fruit-laden boughs of cherry trees was the army’s worst offense. But Yankee stragglers and drunks were another matter altogether. Approaching Gettysburg on July 1, the first day of the watershed battle, Reid found “drunken loafers in uniform” in every farmhouse. “They swarmed about the stables, stealing horses at every opportunity and compelling farmers to keep up a constant watch.” Further, “In the fence corners groups of them lay, too drunk to get on at all.”

Back with the invading Confederate force, British observer Freemantle, on the other hand, was impressed by the lack of Rebel stragglers and the order from on high forbidding indiscriminate foraging in the enemy country. Even so, “in such a large army as this there must be many instances of bad characters, who are always ready to plunder and pillage whenever they can do so without being caught.” Stragglers left behind no doubt would do their harm, thought Freemantle. “It is impossible to prevent this,” he later wrote, “but every thing that can be done is done to protect private property and non-combatants, and I can say, from my own observation, with wonderful success.”

At Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, he also noted, some Texans were ordered to break up a few barrels of whiskey “liberated” in or near the town. The order was a “pretty good trial for their discipline…[but] they did their duty like good soldiers.”

Freemantle, like Pender, was impressed by the good marching order of the Rebel soldiery. As the Confederates closest to the Brit drew near Gettysburg on July 1, they heard firing ahead and began to see the wounded carried back from up front, stripped “nearly naked” and displaying “very bad wounds.” Even so, the men moving forward did not flinch.

“This spectacle, so revolting to a person unaccustomed to such sights, produced no impression whatever upon the advancing troops, who certainly go under fire with the most perfect nonchalance,” wrote Freemantle. “They show no enthusiasm or excitement, but the most complete indifference. This is the effect of two years’ almost uninterrupted fighting.”

Also on July 1, Northern reporter Reid reached the village of Taneytown, Maryland, just eighteen miles from Gettysburg. Here, he was clear at last of the stragglers and drunks seen earlier. Here, all was abustle. “Army trains blocked up the streets; a group of quartermasters and commissaries were bustling about the principal corner; across on the hills and along the road to the left, far as the eye could reach, rose the glitter from the swaying points of bayonets as with steady tramp the columns of our Second and Third Corps were marching northward.”

Robert E. Lee, meanwhile, had learned on June 29 of George Meade’s ascension to command of the Union Army that was catching up to Lee’s own Confederate force. The distinguished Rebel commander saw that events were leading him to a small town to the east, just above the Maryland-Pennsylvania line. “Tomorrow, gentlemen,” he told a group of officers taking a walk with him, “we will not move to Harrisburg, as we expected, but will go over to Gettysburg and see what General Meade is after.”

As for Meade’s possible actions: “General Meade will commit no blunder in my front, and if I make one he will make haste to take advantage of it.”

For that matter, how did either of the two commanders drawing close to Gettysburg strike the unacquainted observer? Freemantle first met Lee the morning of June 30 and was most impressed. “General Lee is almost without exception the handsomest man of his age I ever saw. He is 56 years old, tall, broad-shouldered, very well made, well set-up—a thorough soldier in appearance; and his manners are most courteous and full of dignity. He is a perfect gentleman in every respect.”

The Southern commander didn’t smoke, drink, chew tobacco, or swear. He usually wore a “high black hat,” along with his lengthy gray uniform jacket, blue trousers, and Wellington boots. Neat in dress, “in the most arduous marches he always looks smart and clean.”

Whitelaw Reid, meanwhile, found Union commander Meade early on July 1 at a headquarters half a mile east of Taneytown (named for U.S. Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, who wrote the majority opinion in the famous Dred Scott case). “In a plain little wall tent, just like the rest, pen in hand, seated on a campstool and bending over a map is the new ‘General Commanding’ of the Army of the Potomac,” wrote Reid later. Meade, the correspondent also noted, was a slender, dark-haired, bearded man of middle age, neither handsome nor graceful, “who impresses you rather as a thoughtful student than a dashing soldier.”

While Reid was at Meade’s headquarters, another reporter, Lorenzo Crounze of the New York Times, galloped up with news of a fight developing to the west, near Gettysburg. “Mount and spur for Gettysburg is, of course, the word,” wrote Reid later.

A little earlier Robert E. Lee had heard the distant thunder of artillery. His advance elements obviously had found the enemy, but how many—how serious was the meeting? Lee hurried to Cashtown, just west of Gettysburg, to confer with his Third Corps commander, A. P. Hill, who looked pale and ill. He didn’t know much yet, and Lee rushed on blindly toward the sound of the guns, until he reached Dorsey Pender’s division, three miles outside of Gettysburg. From there, with open country lying before him, he could see the action ahead through his binoculars. The battle had been joined.