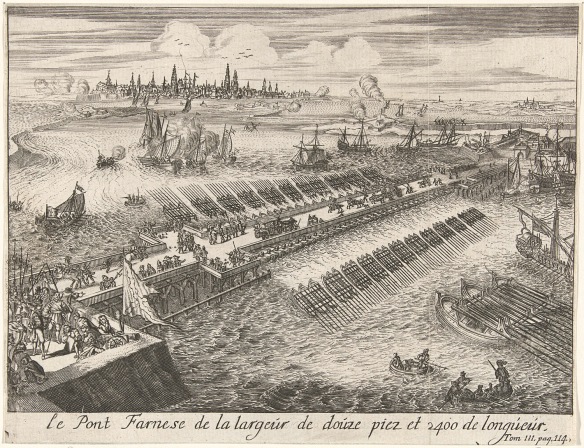

A floating blockade, which was built through the winter of 1584–1585 by two Italian engineers. The task was completed 25 February. Thirty-two barges chained together and anchored to the river bottom formed the center of the boat bridge, measuring 420 yards in length. The 180 yards to either shore were held in place by pilings and covered by a fort on either end. A platform was constructed crossing the entire structure, and an earthen embankment was built on both ends to protect bridge traffic from musket fire. To beat back any potential attack on the bridge from the river, each barge had a cannon mounted fore and aft. Ten guns were placed in the flanking forts, named Santa Maria and San Felice. To further protect the bridge, pontoons along the sides bristled with pointed beams. To round it off, twenty galleys cruised the river.

Date:

August 1584–17 August 1585.

Location:

At the mouth of the Scheldt River, in modern Belgium.

Forces Engaged:

Spanish: 10,000 infantry and 1,700 cavalry. Commander: Alessandro Farnese, duke of Parma.

Dutch: 20,000 troops. Commander: Philippe de Marnix.

Importance:

Spanish victory gave them control of the southern provinces of the Netherlands, modern Belgium, which they retained until 1832.

Historical Setting

In the wake of Martin Luther’s revolt against the Catholic Church, Europe rapidly began to divide into Protestant and Catholic factions. These opposing sides had more than religion to keep them apart, for Rome had long dominated Europe’s politics and economy. Therefore, the supporters of Luther and other Protestant leaders had political and economic independence in mind as well. Northern Europe bred the main Protestant movements, and in German and Dutch states the political revolts were against the Holy Roman Empire, led by the Spanish Habsburg King Charles V. He saw suppression of the Protestant heretics as vital to both his religion and his lands.

In the Netherlands, the northern states tended toward Calvinism while the southern states remained predominantly Catholic. In spite of their religious sentiments, however, the southern states were just as ambitious for independence since Dutch maritime power was on the rise and there were world markets to exploit, markets that the Spanish navy jealously guarded. The main Dutch leaders, particularly William of Orange, were aristocrats and members of the Habsburg court; they found themselves torn between duty to their sovereign and loyalty to their people and their business interests.

King Charles’ son Philip lived in the Netherlands, overseeing his father’s interests and trying to maintain Spanish authority. The local aristocracy got along well with him, but when Philip became King Philip II in 1559, that amity began to wane. Philip came to believe that Protestants just could not be loyal subjects, and his increased taxes on Dutch cities certainly provoked disloyalty. Believing the Church to be the most secure avenue of wealth and popular control, Philip began distancing himself from the Dutch aristocracy while creating a stronger Church hierarchy in the Netherlands. When Dutch Protestants forced Philip’s regent (his half-sister Margaret of Anjou) to ease the laws against “heresy,” Philip responded by sending in the duke of Alba to restore control. Between 1567 and 1572 Alba crushed revolts and executed leaders, but could not convince the population to accept absolute Spanish authority and the resulting high taxes.

Alba raised an army of 30,000 men, but they were primarily German mercenaries, who also served as the bulk of William of Orange’s army. With deeper pockets (at least for the time being), Alba waited until William’s hirelings left him for want of pay. Alba then began taking a series of fortresses necessary to exercise control over the Netherlands. He continued to build his army until it reached 80,000, but that proved too expensive for Philip to maintain. When Alba’s army took Antwerp in 1575, the unpaid mercenaries pillaged the city (the “Spanish Fury”), leaving some 8,000 dead in their wake.

Philip replaced Alba with his nephew Alessandro Farnese, the duke of Parma. With increased silver reserves coming in from the western hemisphere, Parma had fewer financial worries, but the Dutch proved difficult enemies. In 1584 William of Orange was assassinated, and Parma began a major offensive hoping to take advantage of the loss of that stubborn leader. He besieged Ghent, Brussels, and Mechlin, but the key to controlling the southern Dutch states was Antwerp.

The Siege

With Parma’s onslaught in the second half of 1584, the Dutch looked for foreign aid. The country most logical to approach was England, whose Protestant Queen Elizabeth was always eager to thwart Philip’s plans. England, however, still had a strong Catholic minority and Elizabeth was still unwilling to openly confront Spain’s power, although she had been financially aiding William for some time. The Dutch therefore looked to France, whose King Henry III feared having strong Spanish forces to both his north and south. They offered Henry the Dutch throne, but strong Catholic resistance in his country convinced him to decline. Elizabeth began to make overtures and offered an expensive proposition: 4,000 infantry and 400 cavalry in return for possession of two coastal towns as security for her expenses. As the two sides dickered, the sieges went on. Ghent surrendered first in early 1585, with Brussels falling in March. Two other southern cities fell from internal subversion. The longest and most difficult siege was at Antwerp.

Parma led 10,000 infantry and 1,700 cavalry to Antwerp, beginning his siege in October 1584. The city lay on the Scheldt River just inland from the English Channel. It thus was able to maintain itself as long as shipping could be sent from the northern states. The city was defended by some 20,000 men under the command of Philippe de Marnix, whom William had assigned the task. The city’s defenses were sufficiently stout to defy direct assault, so Parma decided that the only option was to block the Scheldt. He designed a floating blockade, which was built through the winter of 1584–1585 by two Italian engineers. The task was completed 25 February. Thirty-two barges chained together and anchored to the river bottom formed the center of the boat bridge, measuring 420 yards in length. The 180 yards to either shore were held in place by pilings and covered by a fort on either end. A platform was constructed crossing the entire structure, and an earthen embankment was built on both ends to protect bridge traffic from musket fire. To beat back any potential attack on the bridge from the river, each barge had a cannon mounted fore and aft. Ten guns were placed in the flanking forts, named Santa Maria and San Felice. To further protect the bridge, pontoons along the sides bristled with pointed beams. To round it off, twenty galleys cruised the river.

Antwerp had the services of an Italian engineer as well: Federico Giambelli of Mantua, later called the “Archimedes of Antwerp.” A Flemish engineer named den Bosch assisted him. The two developed a number of original weapons with which to attack the bridge. Barrels filled with gunpowder and iron stakes were floated downstream without success. Large sheets of canvas were then floated in hopes of catching on the pilings and blocking the current, building up sufficient pressure to break the bridge. This strategy did not work either. A raft loaded with explosives ran aground on one of the banks before it reached the bridge, and a huge barge carrying a thousand arquebusiers also ran aground and was destroyed by Spanish cannon.

The Antwerp engineers finally had some success on 5 April with four massive shrapnel explosives. Giambelli fitted out flat-bottomed barges with a channel of gunpowder running stem to stern. “At the bottom there were bombs, millstones, marble chips, gravestones, chains, nails, and cutting blades. All this was pressed together by iron bolts and the whole mass was covered with wood treated with pitch and strewn with sulfur so that it would appear to be an ordinary incendiary device. The explosion was to be set off at the proper time by clockwork mechanisms” (Melegari, Great Military Sieges, p. 143). Three of the four failed to detonate, but the fourth did incredible damage: 260 feet of bridge destroyed and 800 men killed. Parma himself barely escaped. For some inexplicable reason, no sally from Antwerp appeared. Indeed, Parma’s engineers not only repaired the bridge, but also included movable sections that could be detached to let any future craft float through.

No more great efforts were expended. The siege lasted for another four and a half months, as the defenders gradually starved. They finally attempted a sortie in May, in conjunction with a small relief force. The two managed to link up and destroy the Kouwenstein dike, but the Spaniards soon retook and repaired it. In early August, Parma decided the time had come to challenge the city’s defenses directly. After almost two weeks of fighting, the city citadel finally fell on 17 August.

Results

The city may have held on a few more weeks, but de Marnix had lost his spirit. For the length of the siege he had kept morale high and quashed sedition, but news of the surrender of other major cities deflated him. No major relief force arrived overland and no serious attempt to force the river appeared. French King Louis refused to intervene, and de Marnix had no faith in English promises. When the population began to speak of abandonment by the Protestant northern states, de Marnix began to believe it as well. Even though relief ships were only waiting on a favorable wind, the defenders knew nothing of it.

Parma had a habit of treating defeated cities generously, and Antwerp was no exception. The peace terms called for a return to loyalty to King Philip and the reestablishment of the Catholic faith. Protestants were allowed four years to remove themselves. No Spanish garrison was stationed there, but the citadel was destroyed, to be rebuilt upon the total conquest of the Netherlands. Antwerp’s fall gave Spain control over all the southern Dutch states, which had been heavily Catholic anyway (with some exceptions, like Antwerp). This region became the basis of the modern nation of Belgium, while the northern states ultimately formed the nation of Holland. Many in the region and throughout Europe expected Parma’s ultimate conquest would be completed. It did not happen. The northern states strengthened their hold on the rest of the country’s rivers, and Parma could not force his way across them. Further, the Dutch navy (after the Spanish Armada’s defeat at English hands in 1588) controlled the coastal waters. “The town which Parma, thanks to his indomitable spirit, his military genius, and his knowledge of human nature, had succeeded in conquering, now withered, as it were, beneath his hand” (Geyl, The Revolt of the Netherlands, pp. 200–201).

By the end of the four-year grace period Parma allowed the Protestants, almost all of them had left for the northern states. Primarily merchants, they left when the blockade strangled the city’s trade, as well as to exercise their own religion. Antwerp’s loss proved Holland’s gain. “The peace and order which Parma gave to [the states of] Flanders and Brabant very much resembled the stiffening of death. On the other hand all the best vital forces of the Netherlands people drew together in the small area north of the rivers” (Geyl, The Revolt of the Netherlands, p. 201).

References:

Pieter Geyl, The Revolt of the Netherlands, 1555–1609 (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1958); Vezio Melegari, The Great Military Sieges (New York: Crowell, 1972); Geoffrey Parker, The Dutch Revolt (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977).