These boosts in weapons technology do not necessarily occur at a smooth pace or a predetermined rate. To the contrary, it often appears that technological innovation in military matters is marked by episodic discontinuities – sudden jumps in weapons capabilities that inject radically new performance possibilities. These seismic shifts, characterized as “revolutionary moments,” not only jumble the weapons inventories themselves, they also provide occasion for radical revisions in the organization of military structures, in the concepts of operation for the forces, and in the roles and missions assigned to them.

Important spurts of creativity of this kind do not occur often; historians disagree about which breakthroughs have achieved sufficient magnitude in opening new modes of military operation to qualify as genuine revolutions.[1] Among the most salient historic paradigm-shifting global transformations – the articulation of new things and ideas that interrupt preconceived notions of how to fight – we may plausibly include the following dramatic illustrations:

- The six-foot yew longbow, exploited by a vastly outnumbered English army in the Battle of Crecy in 1346 in northern France at the turning point of the Hundred Years’ War. The archers employed this revolutionary technology – featuring longer range and double the rate of fire of existing crossbows – to devastate a vaunted French corps of armored knights, overnight displacing heavy mounted cavalry as the dominant force in land warfare.

- Sail-powered warships armed with cannons, which in the sixteenth century proved faster and more maneuverable than oared galleys and were capable of destroying an enemy fleet from afar without the peril of boarding the victim’s vessel and engaging in hand-to-hand combat. Naval vessels and naval warfare, which had not evolved much in the two millennia since classical Greek archetypes, were suddenly transformed by French and Venetian leadership, converting ships from mere floating garrisons of soldiers to mobile artillery platforms.

- The Napoleonic revolution, through which the French were able to mobilize a vastly larger army than their opponents (via the levee en masse (mass uprising or conscription)), to motivate that populist cadre with the scent of patriotism, and to improve and standardize the organization and command structure of their formations.

- The adaptation to military operations of Industrial Revolution breakthroughs in communications, transportation, and manufacturing, such as the telegraph, the railroad, and the mass-produced rifled firearm. As illustrated during the American Civil War of 1861–1865, these advances enabled unprecedented speed and coordination in shuttling well-armed troops, equipment, and supplies rapidly to remote theaters of battle.

- A second naval revolution in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, as ironclad ships, steam turbine power, and large rifled cannons (and slightly later, submarines and torpedoes) radically altered the structure of engagements at sea and enabled new modes of combat, such as the strategic blockade. The British 1906 launch of the HMS Dreadnought triggered a naval arms race, as all major powers sought to mimic the breakthrough pulsed by the leading seafaring state of the day.

- The cluster of deadly innovations in World War I, in which different experts would identify tanks, aircraft, radios, or chemical weapons as the most important cutting edge of the modern implements of war. The popular image of stagnant armies mired in incessant trench warfare obscures appreciation of the novel military technologies introduced in that era.

- The even more deadly innovations of World War II, through which the debut of blitzkrieg (lightning war), aircraft carriers, amphibious warfare, radar, and long-range bombing vividly demonstrated the advantages of speed and the sudden assemblage of mass firepower.[2]

- The nuclear weapon, especially when mated to the long-range ballistic missile, which exposed enemy societies – indeed, the entire world – to the specter of mass annihilation within 30 minutes after the push of a button. Although earlier societies had often feared that military innovation would threaten to destroy all human life, by the 1960s or 1970s, that specter became a realistic possibility – and our utter defenselessness swiftly led to altered concepts of war, deterrence, and peace.

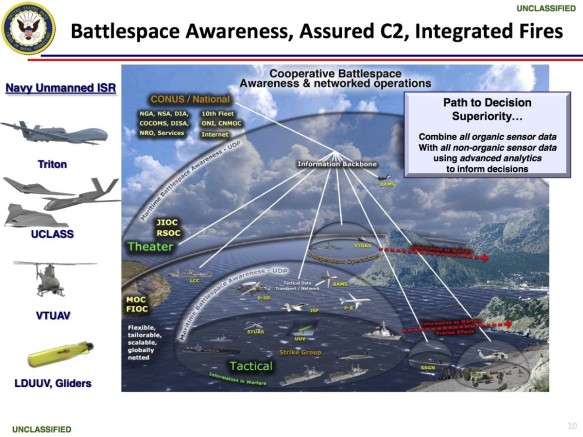

- The space age, which creates the conditions for instantaneous global reconnaissance and communications, improving leaders’ abilities at command and control over the forces in the field and dissipating much of the “fog of war” that has always obscured battlefield conditions.

- The contemporary computer or information revolution and associated quantum leaps in microelectronics, sensors, laser- and other directed energy devices, and automated control technologies, which thoroughly alter both the strategic (big picture, long range) and tactical (localized) aspects of battlefield management and conduct.

These illustrations suggest that a true revolution in military affairs is a rare, complex phenomenon, without standardized features. Sometimes, multiple innovations occur nearly simultaneously, altering combat across a wide range of venues. Sometimes, the revolutionary moment is protracted, as decades are required for countries to recognize the value of the incipient transformation and to inculcate their fighting forces with new understandings and modified technologies. Sometimes, a revolution is driven by, or associated with, a particular agent or sponsor, as with Napoleon’s eponymous innovations; at other times, the change benefits from multiple parents. Often a viable offset or countermeasure will spring up almost as soon as the novel breakthrough itself is registered, swiftly rebalancing offenses and defenses in new equilibria. Frequently, a revolution is not confined solely to the military apparatus, as relevant inventions bleed from the civilian sector into the arena of combat and back again.

Primacy in a revolutionary era can confer significant advantages upon the successful entrepreneur. By effectively marshaling a new weapon, a revised strategy, or a novel concept of operations, even a relatively small country can succeed against more formidable opposition – at least until the rivals also adapt, aping or even improving upon the innovation. Whoever first succeeds in exploiting the chariot, the stirrup, or the iron sword can acquire at least a transitory advantage over larger, wealthier foes – and even ephemeral advantages may be worth seizing.

In all of this, it is a mistake to focus exclusively on new weapons hardware; the novel equipment may be the most visible manifestation of a revolution in military affairs, but even more important is a transformed mode of thought or analysis, a reformation in understanding how modern armies, navies, and air forces can be wielded to maximum effect. Organization, structure, and missions must be revised to accommodate the new hardware, and it is frequently observed that the most important revolution in military affairs must occur in people’s minds and not in their equipment. It is instructive to note, for example, that tanks, mobile artillery, and radios were generally available to many countries prior to World War II, but only in Germany did the leadership seize proper insight regarding revised operational concepts and the new culture of command necessary to create the devastation of the blitzkrieg.

[1] Andrew F. Krepinevich, Cavalry to Computer: The Pattern of Military Revolutions, National Interest, Fall 1993/1994; Theodor W. Galdi, Revolution in Military Affairs? Competing Concepts, Organizational Responses, Outstanding Issues, Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, 95–1170 F, December 11, 1995; MacGregor Knox and Williamson Murray (eds.), The Dynamics of Military Revolution 1300–2050, 2001; Colin S. Gray, Strategy for Chaos: Revolutions in Military Affairs and the Evidence of History, 2002; Jeffrey McKitrick, James Blackwell, Fred Littlepage, George Kraus, Richard Blanchfield, and Dale Hill, The Revolution in Military Affairs, in Barry R. Schneider and Lawrence E. Grinter (eds.), Battlefield of the Future: 21st Century Warfare Issues, Maxwell Air Force Base, Air Chronicles, 1995; Dupuy, supra note 9, at 286–307; Williamson Murray, Thinking About Revolutions in Military Affairs, Joint Forces Quarterly, Summer 1997, p. 69; Stephen Biddle, Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle, 2004; Michael J. Mazarr, Jeffrey Shaffer, and Benjamin Ederington, The Military Technical Revolution: A Structural Framework, Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 1993; Clifford J. Rogers (ed.), The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe, 1995.

[2] William H. McNeill captures the spirit of the moment and the concomitant burst of military inventiveness, writing, “World War II was different. The accelerated pace of weapons improvement that set in from the late 1930s, and the proliferating variety of new possibilities that deliberate invention spawned, meant that all the belligerents realized by the time fighting began that some new secret weapon might tip the balance decisively. Accordingly, scientists, technologists, design engineers, and efficiency experts were summoned to the task of improving existing weapons and inventing new ones on a scale far greater than ever before.” William H. McNeill, The Pursuit of Power: Technology, Armed Force, and Society Since A.D. 1000, 1982, p. 357.