Athens did not tolerate dissent, and, when the Naxians tried to break free in 470, Athens imposed money payments in lieu of the ships Naxos had earlier provided; this was then extended more widely to Athens’ allies, and a number of tribute lists survive that speak loudly for the way Athens was asserting itself in the Aegean. But the Delian League was well matched by a Peloponnesian League, embracing the towns of southern Greece and dominated by Sparta. Thucydides commented on the difference between the two leagues:

The Spartans did not make their allies pay tribute, but saw to it that they were governed by oligarchies who would work in the Spartan interest. Athens, on the other hand, had in the course of time taken over the fleets of her allies (except for those of Chios and Lesbos) and had made them pay contributions of money instead.

Thus Sparta worked with allies; Athens asserted its dominion over dependants. On the other hand, the allies of Athens were impressed by the successful leadership it provided, often far from Greece – the Athenians well understood that foreign victories could be used to promote their own hegemony within the Aegean. In 466 the allies, led by the Athenian commander Kimon, literally smashed to pieces the Persian fleet, numbering 200 ships, off the coast of Asia Minor, at the mouth of the river Eurymedon. The allies struggled manfully against the Persians, sending 200 ships of their own to Egypt to support a revolt against Persian rule (459); this, however, resulted in humiliating defeat. Ten years later, the Delian League sent its fleet under Kimon to make trouble in Cyprus, where the Persians held sway. Meanwhile, Athens bullied rivals and rebels, tightening its grasp over Euboia, while also making peace with the most obvious competitor for hegemony, Sparta, in 446. Since Sparta and Athens had different obsessions, Athens seeking to hold on to its possessions in the Aegean, and Sparta to maintain supremacy in the Peloponnese, it was not difficult to separate their spheres of interest. The real difficulties would arise when lesser towns drew Athens and Sparta into their own squabbles.

The outbreak of the Peloponnesian War can be traced back to events in the Adriatic, in a small but strategically placed town founded on the edge of the land of the Illyrians: Epidamnos. It was a staging-post on the increasingly important trade route that carried goods up from the Gulf of Corinth towards the Etruscan and Greek colonies at Spina and Adria, a route in which Athens was taking an ever stronger interest. Epidamnos had been created by Corinthian colonists from Kerkyra (Corfu); it was thus a granddaughter of Corinth, and, like many Greek towns, it was riven by factional fighting between aristocrats and democrats (436–435 BC). The democrats, under siege from the aristocrats and their barbarian allies the Illyrians, appealed to Kerkyra for help; but the Kerkyrans were distinctly uninterested. They saw themselves as a respectable naval power, with 120 ships (a fleet second in size to Athens), competing at sea with their mother-city of Corinth, with which relations were decidedly cool: the Corinthians were convinced that the Kerkyrans did not show the respect that was due to a mother-city, while the Kerkyrans claimed that ‘their financial power at this time made them equal with the richest states in Hellas, and their military resources were greater than those of Corinth’. Relations deteriorated further when Corinth responded to the appeal from its grandchildren in Epidamnos, and sent colonists to help the besieged town. So an apparently pointless conflict broke out between Corinth and Kerkyra over Corinthian intervention in what the Kerkyrans were convinced were their waters. Kerkyra appealed to Athens for aid: the Kerkyrans argued that Athens, with its mighty fleet, could block the pretensions of Corinth; ‘Corinth’, they said, ‘has attacked us first in order to attack you afterwards.’ They asked to be brought into the Athenian network of alliances, though they were aware that, under the terms of past treaties between Sparta and Athens, which had sought to balance the Delian and Peloponnesian Leagues, this might be viewed amiss:

There are three considerable naval powers in Hellas – Athens, Kerkyra and Corinth. If Corinth gets control of us first and you allow our navy to be united with hers, you will have to fight against the combined fleets of Kerkyra and the Peloponnese. But if you receive us into the alliance, you will enter upon the war with our ships as well as your own.

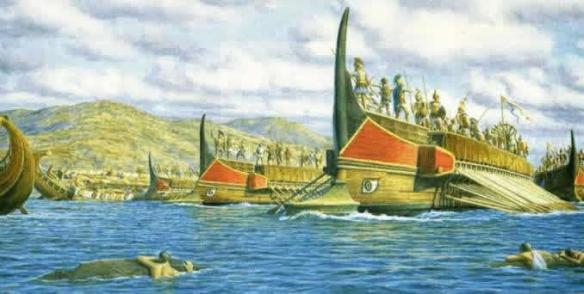

Judging from these words, there was a fatalism about the coming of war. In 433 the Athenians despatched ships to help the Kerkyrans, heading for Sybota, between Kerkyra and the Greek mainland, where 150 ships from Corinth and its allies faced 110 ships from Kerkyra. The main impact of the Athenian fleet was psychological: the Athenian squadron arrived as battle was joined, and, at sight of them, the Corinthian navy scuttled away, convinced that an even larger fleet was on its way, which was not in fact the case. Sparta wisely held itself aloof from these events.