Naginata. A traditional Japanese pole arm whose head consists of a long, high-quality, curved, saberlike sword blade rigidly attached to the staff with an overly long shank or tang. An expert in naginatajutsu, the martial art of wielding this weapon, was a very deadly warrior.

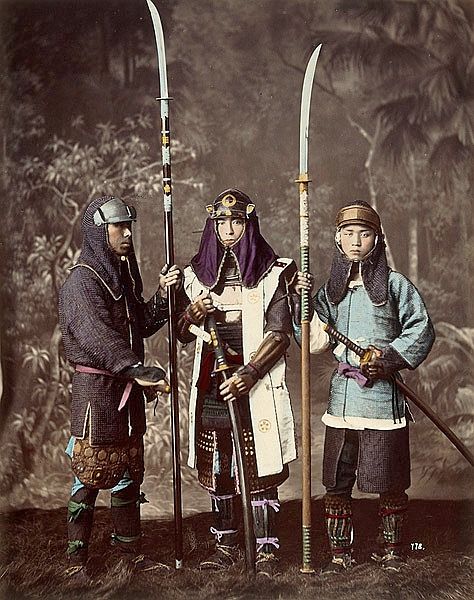

Although regular foot soldiers would often carry swords, usually of inferior quality, their primary weapon was the long spear. Spears of every possible length and weight could be found, but one popular type of spear was the naginata: a curved steel blade placed on a polished wood staff of about 5 or 6 feet in length. The naginata was particularly effective against mounted attacks. The straight yari was the most common type of spear, with a double-edged hardened steel blade placed at the tip.

Often described in English sources as “halberds,” naginata were in fact more like glaives, featuring a long (up to 85–100 cm) curved blade mounted to an oval haft of about 120 to about 150 cm in length, by means of a lengthy tang inserted into a slot in the haft, and held in place by pegs. Unlike the unidirectional hoko, a naginata can be used to sweep, cut or strike, as well as to thrust, and can even be twirled like a baton to keep opponents at bay! It is, in other words, a personal weapon, designed to be used by a warrior fighting largely as an individual, and to maximize his ability to deal with multiple opponents at once. On the other hand, a naginata is a poor weapon for use by troops fighting in rank or in large numbers on a crowded battlefield. Accordingly, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it was in turn displaced by a new form of straight, thrusting spear called the yari.

Exactly when naginata first appeared is difficult to ascertain. There are almost no extant examples of naginata blades that predate the mid-Kamakura period, and none that can be reliably dated to Heian times. The earliest clear reference to a naginata in the written record is a chronicle entry from 1146, which describes a warrior being startled by thunder and reaching for a weapon “commonly called a naginata.” A document dated three months later reports the investigation of a raid on an estate in Kawachi province, in which the perpetrators carried off “20 head of good oxen, 3,000 sheaves of cut rice, 20 haramaki armors, 100 swords [tachi], and 10,000 [sic] naginata.” Both sources write the word “naginata” phonetically, leaving little doubt that the weapon must have been around by this time. On the other hand, as Kondo Yoshikazu points out, the phrase, “commonly called” (zoku ni go su) in the first entry suggests that the term “naginata” was not yet widely known, supporting the conclusion that the weapon was relatively new in the late twelfth century.

Nevertheless, there are earlier, albeit somewhat more ambiguous, references to naginata in the sources. A diary entry from 1040, for example, mentions what may be a naginata carried by a warrior in the capital. In this case, naginata is written with characters that mean long sword, which was the standard orthography until the fi fteenth century. Similarly, a diary entry from 1097 speaks of what may be a naginata, using a similar orthography; a document from 1124 depicts a police official drawing a naginata; and a diary entry from 1110 describes foot soldiers parading through the capital bearing uchimono, an alternative term for naginata in later sources. But it is difficult to be sure whether any of these are indeed early references to naginata or simply literal allusions to very long swords. The phrase drawing a naginata in the 1124 document raises additional questions in this regard, inasmuch as the verb used in later medieval sources to describe unsheathing a naginata is remove (hazusu), rather than draw (nuku), which is normally associated with swords. Similar ambiguities arise with respect to appearances of hoko in later Heian- and early Kamakura period sources. Some clearly distinguish hoko from naginata, while others use the term hoko metaphorically, as in the case of the 1201 chronicle entry that tells of warriors from Echigo, Sanuki and Shinano provinces gracing to assemble and align their hoko. But later medieval sources sometimes confused naginata with hoko, giving rise to the possibility that some of the hoko appearing in eleventh and twelfth-century texts may actually have been naginata.