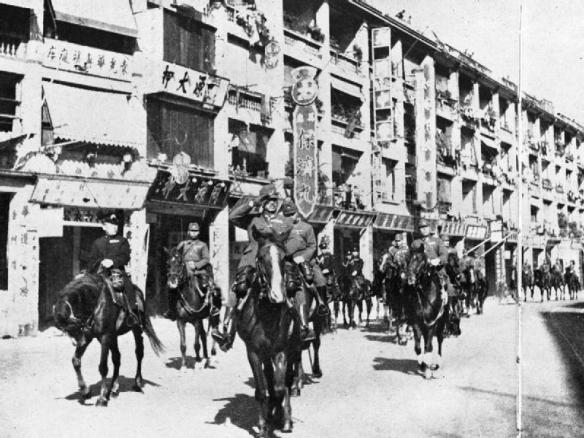

Japanese troops enter Hong Kong and march on Queen’s Road led by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai and Vice Admiral Masaichi Niimi in December 1941, after the British surrender.

Hong Kong was a British Crown colony of some four hundred square miles situated on the coast of southern China, near the city of Canton. The colony, which came under British rule in 1842 as a result of the Opium War, had a 1941 population of 1.6 million people, all of whom were Chinese except for 22,000 European civilians and military personnel. Prior to the war Hong Kong was the headquarters of the Royal Navy’s China Squadron.

The issue of how to best defend Hong Kong, a small territory remote from Britain, or whether to defend it at all, in the event of a Pacific war, was the frequent topic of debate within the British government. In March 1935 General Sir John Dill, director of military operations, had concluded that the colony could not be defended. He had stated that it would be far better to risk losing Hong Kong than to man it too lightly, or to reinforce it to the point where it would become a Verdun-type symbol whose inevitable loss would destroy British prestige at home and abroad. Dill also concluded that the colony, little more than 400 miles from Japanese air bases on Formosa (now Taiwan), was much less strategically important than Singapore, the “Gibraltar of the East,” 1,600 miles to the southwest.

As late as 1937 the British joint chiefs of staff continued to believe that Hong Kong could not be defended, even if reinforced, and that a garrison besieged there could not expect relief for at least ninety days under the very best of circumstances. Even if by some chance the colony could be held, its port would probably be destroyed or at least neutralized as a usable British base by Japanese airpower. Even as the possibilities of successfully defending Hong Kong were becoming weaker, an evacuation of the colony’s civilian population was repeatedly delayed. Such a move, British leaders reasoned, would be interpreted as an abandonment of the Far East, with a resulting loss of face in a time of increasing crisis. It was also seen as damaging to the already low morale plaguing the Nationalist Chinese government. The British thus concluded that Hong Kong was an important, but not vital, outpost that was to be defended for as long as possible in the case of attack by Japan.

A final strategic review in 1939 put British interests in Europe far ahead of their interests in Hong Kong, especially considering that Japanese inroads in China were such that the colony was increasingly isolated. Indeed, by June 1940, sizable Japanese forces were entrenched on the Chinese mainland north of the colony, and other units manned positions athwart the Kowloon Peninsula, cutting Hong Kong off from the mainland. Although a withdrawal of the garrison was recommended in August 1940 by Dill, now chief of the imperial general staff, a recommendation accepted by Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill and his war cabinet, nothing was done to implement the decision. Yet as Anglo-Japanese relations became strained, the British did evacuate some European women and children to Manila in the Philippines in June 1941.

It was common knowledge that Japanese spies had been at work in Hong Kong for years before the war and that they had obtained accurate intelligence on British defenses and troop dispositions. The garrison, commanded by Major General Christopher M. Maltby, normally consisted of only four battalions, two British and two Indian, with additional small support units. In a surprising reversal of policy, however, the British accepted a near-inexplicable offer by the Canadian government to send two additional battalions to Hong Kong, thinking it would lend more credibility to the defense, however doomed it might be in the long run. Thus Canadian troops, the first to see action in World War II, sailed for Hong Kong on October 27, 1941. As weak as the British were on the ground, their air and sea arms were even more inadequate, consisting of seven aircraft, eight motor torpedo boats, and four other smaller gunboats. The twelve thousand regular troops were augmented by the Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery and citizen soldiers of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defense Force.

General Maltby was faced with a difficult tactical situation, having to defend a great deal of territory with few resources. The principal defensive line for the colony was placed just three miles north of Kowloon in the Leased Territories rather than farther inland. Manned by three battalions of Indian and Scottish troops, it was far too long for the available forces. Another three battalions were deployed on Hong Kong Island itself, including the recently arrived Canadian units. Even though a Japanese assault had long been expected from the landward side of the colony, little else could be done considering the general British strategic situation in Asia at the time.

Early on December 8, 1941, Japanese bombers from Formosa destroyed all seven British aircraft in a surprise raid on Hong Kong’s Kai Tak airfield, while twelve battalions of the Twenty-third Army’s 38th Division, commanded by Lieutenant General Sano Tadayoshi, crossed the Sham Chun River into the Leased (New) Territories. In Britain, on hearing of the start of the attack, Prime Minister Churchill declared that the eyes of the world were on Hong Kong and that the garrison should resist to the end. Yet within twenty-four hours, by the evening of December 9, Japanese forces had breached the main British defenses, known for some obscure reason as the Gindrinker s Line, and had taken a crucial redoubt. This success made the already overextended British positions untenable and forced Maltby to order a retreat. British forces quickly fell back, and Kowloon was in Japanese hands by December 12.

After Maltby’s withdrawal to Hong Kong Island, a move later described as too hasty, Sano began to bombard Victoria with artillery on December 13, soon followed by heavy air attacks. These bombardments badly damaged the British naval force and caused fires in the central business district. Following the delivery of a surrender ultimatum on December 14, an ultimatum which Maltby rejected, Japanese troops attempted to cross to Hong Kong Island the next day, but were repulsed. Three nights later, on December 18, the Japanese tried again, and landed in strength between North Point and Aldrich Bay. Their troops quickly penetrated the island’s defenses and drove to Deep Water Bay in the south, splitting the British forces in two. Motor-torpedo boats tried to stem this tide by attacking vessels carrying Japanese reinforcements, but Japanese air superiority was complete and British naval losses were heavy. However, British resistance was so stiff that on December 20, General Sano was forced to halt all attacks in order to reorganize his forces.

Time, manpower, and resources, however, clearly favored the Japanese. By December 24 the surviving British defenders were exhausted, and water and ammunition supplies were nearly exhausted. The Japanese bombing and the resulting fires had destroyed water mains, and Japanese forces controlled the reservoirs serving the colony. On the afternoon of Christmas Day, 1941, a ceasefire was arranged, and that evening the British governor surrendered the colony unconditionally to Lieutenant General Sakai Takashi.

Hong Kong’s garrison had held for eighteen days, far short of the ninety days predicted, but had put up a much stouter resistance than that offered at Singapore. Japanese casualties numbered approximately 2,700, and the British suffered 4,400 casualties. Only a few people managed to escape into China, and most Europeans become prisoners of war. In the aftermath of the surrender, as elsewhere in Asia and the Pacific, the Japanese committed numerous atrocities against Chinese and Europeans. Hong Kong was in Japanese hands for the remainder of World War II, and was returned to Great Britain after a brief surrender ceremony at Government House on September 16, 1945.

FURTHER READING Birch, Alan, and Martin Cole. Captive Christmas: The Battle of Hong Kong, December 1941 (1979). Lindsay, Oliver. The Lasting Honour: The Fall of Hong Kong, 1941 (1978). Clayton D.Laurie