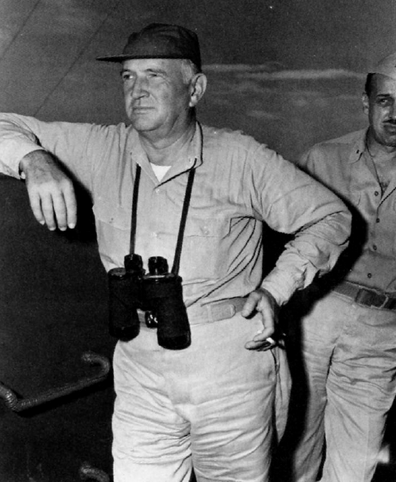

Jesse Oldendorf

Assuming that Jesse Oldendorf fought a surface battle with Kurita it would have been a lot like this!

If Kurita kept coming he would have collided with Jesse Oldendorf’s battleline of Pearl Harbor veteran battleships. Disorganized he would have a major surface battle on his hands with his own scattered ships all over the place. Oldendorf’s problem is that he’s short of naval armor piercing rounds and his destroyers are short of torpedoes where he’s just destroyed Nishimura’s ragtag fleet in the Surigao Strait.

It would have been Oldendorf’s mission to act as a cork until the Third Fleet came up to reinforce. Walter Krueger’s Sixth army would have been savaged by Kurita’s fleet for maybe a day until McCain hurried up to bomb him into destruction or surrender. Presumably by this time a furious Nimitz would have Halsey relieved and under arrest and Lee as next senior Admiral would be pounding south with Sherman leaving Mitscher north with instructions to hammer Ozawa using Bogan’s carrier group. If Oldendorf can hold Kurita for as little as six hours the Battle of Homonhon should have been spectacular and very one sided as the cross fire of US aircraft and the crushing firepower of the US Pacific battleline would have replayed the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay with this difference that the US fleet was a far better force than the one the feckless Admiral Ainsworth mishandled during that battle. Kurita would have been slaughtered.

The U.S. presidential election of l944 was the first mid-war election for America since l864, when Lincoln ran for reelection during the Civil War. The Great Emancipator’s slogan had been, “Don’t change horses in midstream.” Though FDR did not use the phrase himself, many of his supporters did.

Nazi Germany was clearly on the ropes. Paris had long been liberated, and Anglo- American forces were battling into the homeland of the Reich itself.

The Japanese had suffered a number of stunning defeats, but the Pacific war still loomed. From all indications, Roosevelt was about to win an unprecedented fourth term, though by a narrower margin than ever before.

It was late October. A major naval battle lay ahead in the Pacific, but only the Japanese knew it was coming. The battle would be of such scope and importance that it might not only affect the course of the war, but perhaps even swing the U.S. election the other way. And the key figure would not be an American politician, but a Japanese admiral.

The Battle That Could Have Been

Takeo Kurita was the naval officer who, at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. His actions had the potential for major military and political ramifications.

Takeo Kurita was born in Japan in l889. He was a career naval officer who took part in a number of important operations in the Pacific. Kurita had led an amphibious assault against the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies in early l942. Several months later, he took part in the Battle of Midway (where he was assigned to support the landing of Japanese troops on the island), which was called off when Japanese naval forces were badly mauled. Kurita also saw action at Guadalcanal, where his force successfully shot up Henderson Field.

Kurita’s role in World War II will forever be known in naval history as the battle he won and then threw away. It will be regarded as one of the great “what if?” debates of history.

Entering the San Bernardino Strait

In October l944, the Japanese were told, apparently by the Soviet ambassador to Japan, that Douglas MacArthur was about to invade the Philippines.

The initial U.S. landings began on the island of Leyte on October 2l, 1944. The Japanese strategy was to divide up their fleet into four separate forces, each with a specific route and mission.

Two forces, one under Vice-Admiral Ahoji Nishimura and a second under Vice- Admiral Kiyohide Shima, would take separate routes but meet to attack Leyte from the south.

The third force was led by Vice-Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa. He was the decoy, designed to offer a juicy target to the aggressive William F. Halsey. The idea was to draw Halsey away from the San Bernardino Strait, which his fleet was guarding. Halsey was protecting the American amphibious forces landing troops on Leyte.

Kurita’s fourth force was then to enter the strait and demolish the American landing forces at Leyte.

The deception worked. Halsey went for it hook, line, and sinker. He took off after Ozawa and the strait was wide open to Kurita. The original Japanese plan called for him to link up with Shima and Nishimura to wipe out the landing forces. But there was a lot of action along the way, and Shima and Nishimura never made it to their destination.

As part of the attack plan, the Japanese sent planes from land bases in the Philippines and carrier-based planes from Ozawa’s carriers. Kamikazes (suicide planes) struck American ships; American carrier planes retaliated with their own firepower.

A Battle and a Final Retreat

The Pacific area around the Philippines was filled with battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and other ships of all sizes. The series of battles known collectively as the Battle of Leyte Gulf would be called the greatest sea battle in history, one that extended over an area of half-a-million square miles.

Before reaching the San Bernardino Strait, Kurita’s force had run into trouble. First, his flagship was hit by U.S. submarines and sunk; he had to board another. Further along the way, his force was attacked by carrier planes, with additional losses. Though his fleet was damaged, it was still extremely powerful.

When he arrived at the San Bernardino Strait, it was wide open, because Halsey had gone after Ozawa. As Kurita sailed in, unidentified ships were spotted ahead. Kurita was not sure whether Ozawa had been successful in luring away Halsey. Could those unidentified ships be Halsey’s fleet?

What Kurita did not know was that the American ships that lay ahead was a tiny group of escort carriers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts under C.A.F. Sprague. The American ships had, at maximum, 5-inch guns compared to the Japanese 14-, 16-, and 18-inchers.

Sprague immediately set off a smoke screen and closed in. Luckily, a squall came up. Kurita had no idea what he was facing.

Hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned, the Americans fought so savagely that Kurita believed he was facing a major American force. After more than two hours of battle, he turned around and sailed home.

What if?

The Battle of Leyte Gulf officially ended on October 26, 1944. Back in America, Election Day was only a week away. Now comes the “what if?”

What if Kurita had sailed on, destroyed the American landing craft, and killed many U.S. troops on the Leyte beaches? Such a horrendous defeat might well have swung the balance in favor of New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, the Republican candidate running against FDR.

A defeat in Leyte, plus a loss at the Battle of the Bulge two months later, might have been enough for a new administration to take a fresh look at “unconditional surrender.” Might it have tried to offer terms? Would a United Nations have been formed based on the Dumbarton Oaks plan set up by Cordell Hull? It is all speculation; we shall never know.

Admiral Kurita, the man whose missed opportunity might have changed the shape of the post-war world, died in 1977.

#

The Sho-Go was a desperation move by the Imperial Japanese Navy in a bid to stop the American juggernaut approaching the Philippines. The Japanese knew they did not have the ships or planes to seriously challenge the USN, and that the best they could hope for was a to achieve a temporary setback to the American timetable.

They hoped to do this by disrupting the American landing at Leyte Gulf and destroying a significant portion of the invasion force before it could establish itself ashore on the island of Leyte. In order to do this, they hoped to lure the vastly superior Third Fleet away by sacrificing their carriers (which had few aircraft remaining) and attacking MacArthur’s 7th. fleet with their still formidable surface fleet under Admiral Kurita.

Unfortunately for Kurita, news of the American landing force approaching Leyte did not arrive in a timely manner, so by the time he was able to get his fleet near Leyte Gulf, American forces had already been ashore for five days and had achieved all of their initial objectives. Most of the logistical ships supporting the landings had already unloaded and departed the area. The remaining transports and supply vessels were under orders to depart on an hour’s notice and would have escaped down Surigao Strait before Kurita could bring them under fire. MacArthur had sufficient supplies ashore for at least three weeks of operations. So ground operations would not have been affected.

Furthermore, MacArthur’s Seventh Fleet included six old BB’s which nevertheless were extremely dangerous opponents, though with limited AP ammo. It’s unlikely that Kurita would have had much ammo or fuel left after destroying Taffy 3. Even if they had been able to get past MacArthur’s old BB’s, he would have been under strong air attack from the remaining CVE task groups and in the very restricted waters of Leyte Gulf. Kurita had virtually no chance of successfully accomplishing his mission of destroying the landing forces or of inflicting significant damage on the troops already ashore, thus the Leyte landings would not have been defeated no matter what course Kurita chose.

As far as Japanese counterattacks against Allied positions in the Pacific is concerned, it wasn’t going to happen at this stage of the war, no matter how lucky the Japanese got at Leyte Gulf. The Third Fleet, vastly superior to the whole Japanese Navy at this point, would still have been intact. Any Japanese attempt at another Pacific offensive would founder on this one fact alone. The Japanese did not have, in late 1944, the ships, planes, logistical shipping, fuel, and other resources required to mount any sort of offensive operations in the Pacific, even in the Philippines. All Japan could do was wait for the coup de grace to be delivered by American naval and air power.

Leyte Gulf: Second World War at Sea

“Always seize the moral high ground in any conflict. It’s a great place to site your artillery” – Ed Rotondaro