The Sedan sector in detail: 13 May 1940

The greatest German weapon in 1940 was not overwhelming military superiority but surprise. The failure of the French to predict the locus of the German invasion must rank as a failure of intelligence as dramatic as the American failure to predict Pearl Harbor or the Israeli failure to predict the Egyptian attack in 1973. There had in fact been ambiguous intelligence signals, but so often the history of intelligence in warfare supports the axiom that intelligence information tends to be sifted to reinforce received ideas rather than to overturn them. In June 1944 it took weeks before the German High Command accepted that Normandy was the real site of the invasion and not a diversionary tactic to cover the real attack that would come in the Calais area. The French intelligence services in 1940 did pick up quite a lot of information on the possibility of an Ardennes offensive— for example, on 13 March 1940 it was reported that a lot of bridging equipment was being assembled in Germany opposite the Luxembourg border, two days later that an increasing number of tanks were being deployed opposite south Belgium and Luxembourg—but even more about the possibility of a German move through Switzerland. The problem was how to distinguish genuine information from ‘noise’. The cumbersome French command structure meant that there were no very clear mechanisms for the collation and centralization of intelligence information, especially after Gamelin split the headquarters up in January 1940. According to one historian ‘no senior officer had the task of assimilating intelligence and relating it to operational planning’.

It is the supreme irony of Gamelin’s career that a man so cautious and rational should have taken—and lost—such a massively risky gamble. Perhaps it was Gamelin’s very rationality and caution that let him down: he could simply not imagine that the Germans would take the extraordinary gamble of sending the bulk of their armoured forces through the Ardennes. But Gamelin sometimes seems to have been temperamentally unwilling to confront unpleasant realities, as if any problem could be finessed by charm, luck, and personal contact. Very characteristic in this respect were his expectations, based only on his secret and informal contacts with van den Bergen, that Belgium would suddenly abandon neutrality in 1939 because this was what would best have suited France.

On the other hand, Gamelin cannot be made a scapegoat for everything that went wrong in France in 1940. In the historical literature on 1940 poor Gamelin cannot win. Because, unlike Georges, he did not break down in tears, he is accused of passivity and detachment. He is accused by some historians of locking himself away at Vincennes, but during the first five days of the battle he visited Georges frequently—twice on 14 May necessitating about four hours of travel—which leads to his being accused by another historian of wasting too much time in this way. In many respects Gamelin was the prototype of the general as administrator, with many of the qualities of those military managers such as Generals George Marshall, Alan Brooke, or Alexei Antonov who were the real architects of the Allied victory in 1945. It was Gamelin’s tragedy that he did not have the chance to employ his undoubted qualities where they would have been most useful.

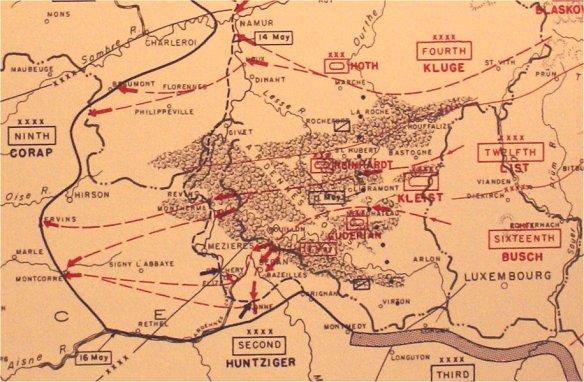

But the problems of the French army in 1940 went far beyond Gamelin. In 1914 Joffre’s strategic mistake had been equally disastrous but there was time to remedy it. In 1940 there was too little time. The absence of Giraud’s troops was not the only reason for this. One problem was that even once the High Command had realized that the main German thrust was through the Ardennes, it still failed to read German intentions correctly. Georges operated initially on the assumption that the Germans would pivot south-east towards the rear of the Maginot Line, or possibly through the centre of the Second Army, but not that they would swing west into the right flank of the Ninth Army. Even when on the night of 13–14 May Georges did form a special detachment under General Touchon to close the gap between the French Second and Ninth Armies, he did not pay significant attention to the right flank of the Ninth Army. He may also have been lulled here into a false sense of security by the successful resistance of the French forces at Monthermé for two days. Thus, Georges’s countermeasures played into the hand of the Germans and possibly aggravated the French situation once the Germans had broken through: there were almost no troops ready to place in their path. Georges had also been reluctant to move troops from behind the Maginot Line—possibly because of his fear that they might be needed to deal with an attack through Switzerland: this misplaced fear was another major intelligence failure.

More serious even than the French military’s slowness to read the direction of the German attack was their incapacity to grasp the nature and speed of warfare as practised by the Germans in 1940. Even after the German break-through, the French were sure that it would eventually run out of steam, and allow them to plug (colmater) the gap. In the First World War, break-throughs of this kind had always slowed down owing to the exhaustion of the troops, and supply and logistical difficulties. From the beginning to the end of the battle, what is most striking about the French response in 1940 is its slowness—whether General Lafontaine’s delayed counterattack at Sedan on the morning of 14 May, or General Flavigny’s even more delayed attack on the next day, or the delay in sending the First DCR against Rommel, and so on. The first crossing of Rommel’s men at Houx occurred before midnight on 12 May, but General Martin, in command of the XIth Corps (18DI and 22DI), was not told anything until 7 a.m. on 13 May, and Corap, who could not be contacted at first, did not know how serious the situation was until the evening.

The truth is that the French were faced with a kind of fighting for which they were completely unprepared—the opposite of the methodical warfare (bataille conduite) for which their doctrine prepared them. One striking difference between the two sides was the conduct of the senior commanding officers. The German commanders were closely involved in the battle, while their French counterparts usually remained in the rear. General Lafontaine of the 55DI, operating from his command post about 8 km behind Sedan, or General Huntziger, from his command post at Sennuc, about 45 km behind the line, were quite different from commanders like Rommel, throwing themselves personally into the fray. Of the four French regiments involved in fighting at Sedan, none lost its commander, whereas the Germans lost a number of key commanders. This was nothing to do with cowardice; it was a reflection of different doctrinal approaches: the ‘methodical’ battle required the senior commanders to stay in their command posts and keep their hand on ‘the handle of the fan’ rather than get too closely mixed up in the action; the German doctrine of ‘mission oriented’ tactics encouraged initiative on the part of lower-level commanders.