In the Song of Roland there are references to “double mail” and “triple mail”, while in his account of the fight between Richard of England and William of Barres, the poet Guillaume le Breton refers to the “thrice-woven hauberk” of the combatants. In terms of the usual way of making mail, in which each ring was threaded with four others, this is a nonsense. It is equally unlikely that anyone would have worn three full hauberks. It is possible to weave mail very densely so that each ring is interlocked with six others, but no Western example is known: however, that does not mean it did not happen. Perhaps Guillaume meant that these two wealthy and important men had reinforced the chests of their hauberks with additional strips of mail. In this same passage, Guillaume le Breton speaks of plates of steel being inserted under the hauberk and the aketon. This is the earliest evidence for the use of plate armour. Gerald of Wales describes the Norse wearing coats of “iron plates skilfully knitted together” when they attacked Dublin in 1171, but this anticipation of the later medieval “coat of plates” never seems to have become popular. Furthermore, another layer of protection was introduced by the mid-thirteenth century, when the padded surcoat was being replaced by one in which strips of iron were riveted to its inside.

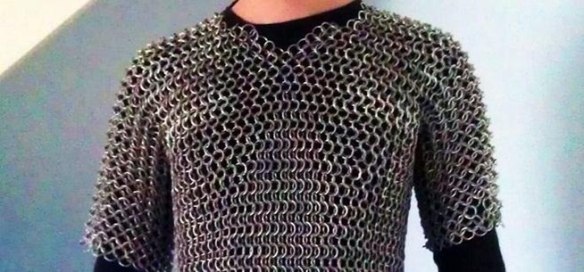

Mail provided protection to the wearer while leaving him freedom to move. Those who have worn modern examples of chain mail stress that a belt helps to redistribute weight and makes the garment more comfortable to wear. No belts are shown in the Bayeux Tapestry, but they do appear in later illustrations. Differential ring sizes were a way of tailoring the hauberk to the contours of the human body, but they may also have served to lighten it – in the St Petersburg armour, heavier rings occur high on the chest and smaller, lighter ones lower down. Even in crusader settlements in the East where heat might have inclined men to lighter forms of protection, the Franks clung to Western mail. They did adopt the hazagand, a mail jerkin covered with fabric on the outside and padded within, first mentioned in the Chanson d’Antioche, but the general preference for Western armour suggests that it was effective.

Contemporaries, indeed, commented how well knights were protected, although presumably wealthier men had the best armour. At the siege of Falaise in 1106, Robert Fitzhamon received a heavy blow on the helmet which left him an idiot until his death, but Henry I survived a serious strike at Brémule in 1119. In his memoirs, the Arab nobleman Usamah tells us of an encounter with Franks in which his cousin was thrown from his horse and repeatedly stabbed by their footsoldiers before being rescued, and comments that he was saved by his mail. On another occasion, he jabbed his lance at a Frankish knight who seemed to be wearing only a surcoat. The knight was so badly hurt by the blow that he doubled up in the saddle, dropping his shield and helmet. However, the man recovered, because under the coat he was wearing mail. But the mail had to be properly prepared. When Earl Patrick of Salisbury was ambushed and killed in Aquitaine, William Marshal (Guillaume le Maréchal) managed to slip on his hauberk and fight, but this did not protect him from a severe sword-wound in the thigh, for he was not fully equipped. Usamah says that his father was badly injured by an enemy spear because a groom had left undone the fastening of his hauberk.

The constant effort to improve protection which ended with the knight swathed in many layers – steel plates, padded a aketon, mail, perhaps sometimes in double or triple layers, a leather breastplate and a padded and later armoured surcoat and coat of plates – is suggestive of the shortcomings of mail. It is difficult to see how any mail could resist a direct hard thrust from a couched spear, backed by the momentum of a mounted man. Guillaume le Breton says that Richard I and William of Barres galloped at each other, spears lowered, and only the plate armour finally stopped the lance, which had pierced the shield, torn the “thrice-woven” hauberk and holed the aketon. The consequences of such a blow could be terrible:

Nought for defence avails the hauberk tough,

he splits his heart, his liver and his lung

And strikes him dead, weep any or weep none. (Sayers)

Our best evidence of the ferocity of medieval warfare comes from the injuries inflicted on the victims of the Battle of Wisby in 1361. These caused an eminent anatomist to remark: “It is almost incomprehensible that such blows could be struck” and he explained their effectiveness by suggesting that attackers “stepped or jumped forward” as they struck their blow. Wisby was a largely infantry battle, and perhaps a man on horseback could not strike so hard, but cavalry engagements involved extremely close-quarter fighting. Usamah reports how one of his men escaped after his head was caught under the armpit of a Frank in a skirmish. The Bayeux Tapestry shows that arrows could penetrate mail, and crossbow quarrels must have been deadly. The likelihood is that while it could not stop a true blow, mail was very effective against glancing blows which, in the confused hacking-match of battle, must have been far more common.