Japan’s emergence from the Sino-Japanese War (1894– 1895) as an East Asian power forced the Western nations to reassess and safeguard their interests in the region, especially in Qing-dynasty China (1644–1912). Russia quickly mobilized the Triple Intervention (with France and Germany) to forestall Japan’s possession of Liaodong Peninsula in southern Manchuria as a ceded colony and secured China’s agreement in 1896 to extend the Trans- Siberian Railway through Manchuria to Vladivostok. The lure of financial gain also fueled fierce competition in floating the three major loans (one Franco-Russian and two Anglo-German) for Beijing’s indemnity payments to Japan. All this, and more, presaged the escalation of foreign rivalries in postwar China that peaked in the “scramble for concessions” from 1897 to 1899.

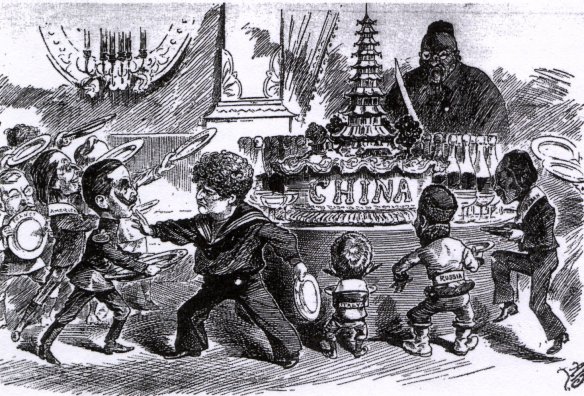

The frantic race began when Germany acquired compensations for two German priests who had been murdered in Juye, Shandong Province, in November 1897: the lease of Jiaozhou Bay and the adjoining Qingdao area for ninety-nine years and Shandong as a “sphere of influence” with exclusive railway and mining rights. Russia followed with the concession of the southern end of Liaodong for twenty-five years, including Lüshun (Port Arthur) as a naval base and Dalian as a trading port, with the right to connect both by a railway with the Trans-Siberian extension in the north. Meanwhile, France consolidated its penetration into China’s southwest by securing Qing assurances not to alienate Yunnan, Guangxi, and Guangdong provinces to other powers, the right to construct railways joining this region with French Vietnam, and the lease of a naval base in Guangzhouwan in Guangxi for ninety-nine years. In addition, China agreed to seek French assistance if a new postal service was to be established in the future.

In parallel action, Britain obtained comparable concessions: China’s retention of a British subject as inspector general of the Maritime Customs for as long as British trade with China surpassed that of other countries, a ninety-nine-year New Territories leasehold contiguous to its colonial holdings in Kowloon and Hong Kong Island, and the promise not to alienate any of the Yangzi Valley provinces to other powers. (This last concession prompted the German response that, unlike Germany’s primacy in Shandong, non-alienation did not actually give Britain a foothold and did not, therefore, preclude the Yangzi Valley, a so-called British sphere of influence, from remaining “unreservedly open to German enterprise.” As such, not all “spheres of influence” were the same insofar as the interests of individual powers were concerned.) Finally, Britain leased, with German understanding, Weihaiwei in northern Shandong as a naval base for twenty-five years, a strategically inferior gain justified by London as a “cartographic consolation” in view of German and Russian preponderance in North China.

Italy was the only country that tried but failed to benefit from the scramble; its attempt to lease Sanmenwan in Zhejiang was rejected. Japan also joined the fray by getting Chinese assurance not to alienate Fujian Province opposite its colony, Taiwan, to another power. Distracted by the Spanish-American War (1898), the United States advanced no claim but communicated the Open-Door Note (originally, a British idea) in 1899 to Germany, Russia, Britain, Japan, Italy, and France, pleading for the “perfect equality of treatment” of all countries within the various “spheres of influence.” Hailed by the American press as a diplomatic coup that possibly saved China, the note elicited only lukewarm responses from the recipient states. Wariness about the financial, military, and political burdens of colonizing China’s vast, populous territory deterred the powers from actually partitioning the Qing Empire.

The overseas quest for naval bases and for mining, loan, and railway projects signaled the importance of sea power and financial imperialism in late nineteenth century global politics. The Qing court was too weak to resist most of the foreign demands and managed only to modify some of the harsh terms. As the sense of doom thickened, the search for relief by both the government and the educated elite culminated in the throne’s inauguration in June 1898 of what became the Hundred Days’ Reform.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Morse, Hosea Ballou. The International Relations of the Chinese Empire. 3 vols. London: Longmans, Green, 1910–1918. Otte, Thomas G. The China Question: Great Power Rivalry and British Isolation, 1894–1905. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. Schrecker, John. Imperialism and Chinese Nationalism: Germany in Shantung. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971.