Although the tank only made its first halting appearance on the battlefield in September 1916 during World War I, it quickly be – came the dominant weapon system in modern ground combat. Combining both of the key elements of combat power—fire and maneuverability—the tank was also the product of the major paradigm shift from muscle (both human and animal) power to machine power that occurred in warfare between 1914 and 1918.

Despite its impressive armor and armament, the tank is not invulnerable, nor can it single-handedly accomplish every task on the battlefield. Tanks can be defeated by physical barriers, land mines, aircraft, artillery, other tanks, and a wide range of infantry weapons. For these reasons, tanks are most effective when they are committed as part of a combined-arms team. Accompanying friendly infantry and engineers reduce barriers and neutralize enemy infantry fire. Friendly aircraft augment the fires of the tanks, suppress enemy antitank fire, and attack enemy tanks. Friendly artillery suppresses enemy antitank and antiaircraft fire and supports the accompanying infantry.

The key problem in coordinating all of these elements of the combined arms team is the varying speeds at which they maneuver, especially when under fire. Tanks and aircraft obviously move much faster than conventional infantry or towed artillery. The requirement to keep up with the tanks gave rise to modern mechanized infantry and self-propelled artillery. Nonetheless, in the years since the end of World War I, armored warfare theorists have gone through several cycles of advocating that tanks and airpower could do it all, with infantry and artillery relegated to mopping up operations. With each new technological advancement in armor or airpower, it seemed to work for a while. But infantry and artillery weapons technology then caught up, and the cycle began all over again. This pattern can be seen very clearly in the history of the Arab-Israeli wars. Tank warfare, therefore, is far more complex than simple tank-against-tank fighting.

Tanks are far more terrain-dependent than infantry, just as airpower is far more weather-dependent than artillery. Tanks are more effective in open, flat terrain where their ability to maneuver is not restricted by roads, vegetation, or extreme elevations. The deserts of the Middle East are classic tank warfare terrain, and virtually all of the major tank battles since World War II have occurred in that part of the world.

The various categories of tank kills are a function of the damage done to the tank combined with the tactical situation. A mobility kill occurs when the tank’s power train or running gear has been damaged to the point that the tank cannot move. The tank may still be able to fire its weapons, but its inability to maneuver severely degrades its combat value. A firepower kill occurs when the tank’s main gun or its fire control optics and electronics have been severely damaged. A total kill occurs when the tank can neither move nor fire. This usually means that the tank has been totally destroyed, but it can also mean that the crew has been killed, even though the physical damage to the tank itself may be relatively light. The crew, obviously, is the most vulnerable element of any tank. It is also the most easily replaced as long as highly trained crew members are available.

Whether fired by artillery, aircraft, another tank, or infantry weapons, the warheads of all antitank rounds are classified as either chemical energy or kinetic energy. Most main battle tanks are capable of firing both types of rounds through their main guns. The most common and effective chemical energy projectile, the high-explosive antitank (HEAT) round, has a shaped charge warhead that relies on the Munroe Effect to burn a hole through the tank’s armor in the form of an expanding cone. What actually kills the tank crew members is the fragmented armor of their own tank. HEAT rounds can also set off fuel and ammunition fires. Nonexploding kinetic energy rounds are very heavy and dense and are fired at an extremely high velocity. The most common is some form of sabot round in which an outer casing falls away as soon as the round leaves the muzzle. On impact the sabot literally punches its way through the target’s armor. The result inside the tank is no less catastrophic than that caused by a HEAT round.

Because kinetic energy rounds require a flat, line-of-sight trajectory and an extremely high velocity, they must be fired from a gun, as opposed to a howitzer, and from a very heavy platform. Thus, only tanks and antitank artillery can fire sabot rounds. A tank’s most vulnerable area to a sabot round is at the slip ring, where the turret joins the main hull. Smaller nonsabot kinetic energy rounds are fired from rotary or fixed-wing aircraft armed with special antitank Gatling guns that deliver a high volume of fire to defeat the target’s armor, usually from above where the armor is the weakest. Although common in World War II, purpose-built antitank artillery fell into disuse in the years following 1945. By the 1960s, the Soviet Union, West Germany, and Sweden were among the few remaining countries still building antitank artillery. Most armies came to regard the tank itself as the premier but certainly not the only antitank weapon.

Chemical energy rounds do not require a heavy launching platform and are thus ideal for infantry antitank weapons, which include rocket launchers, recoilless rifles, and antitank guided missiles (ATGMs). When wire-guided ATGMs first appeared in the early 1970s, they were quickly fitted onto helicopters. They were soon replaced by a new generation of ATGMs with fire-and-forget guidance systems. Field artillery HEAT rounds include projectiles that are guided onto the target by a forward observer using a laser designator and projectiles that produce air bursts over tank formations, releasing numbers of HEAT submunitions that attack the tank’s top surfaces.

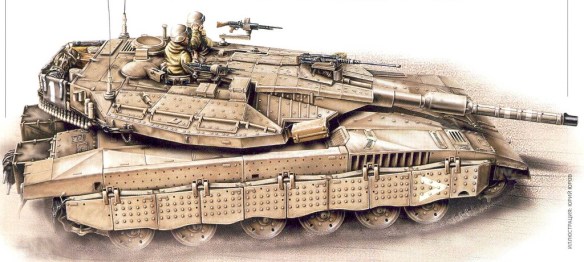

The best way to defeat a HEAT warhead is to cause it to detonate prematurely, which will prevent the Munroe Effect from forming properly on the outer skin of the tank’s armor. Something as simple as a mesh outer screen mounted on the side of a tank with a few inches of standoff distance will cause that premature detonation. Reactive explosive armor, also called appliqué armor, mounted on the tank’s integral armor is also relatively effective against HEAT rounds but is not at all effective against sabot rounds. Each element of reactive armor contains a small explosive charge that detonates when it is hit, causing the impacting HEAT round to detonate prematurely, spoiling the Munroe Effect. Finally, the sloped surfaces of the tank’s armor can cause the HEAT round to deflect, which will also spoil the Munroe Effect. Sloped armor surfaces can also deflect sabot rounds in certain instances.

Tanks can be defeated by a blast from conventional high explosives if the charge is large enough and close enough. Antitank mines frequently produce mobility kills by blowing off the tread or damaging the road wheels and sometimes produce total kills. High explosive projectiles delivered by artillery or air require a direct or very close hit, which usually exceeds the circular probable error of all but the most advanced precision munitions. Field artillery can also be used to place antitank minefields deep in the enemy’s rear by firing special cargo-carrying rounds that disperse the mines upon detonating in the air. The mines are relatively small, usually just large enough to produce a mobility kill, but the advantage is that the enemy tank is immobilized far from the line of contact.