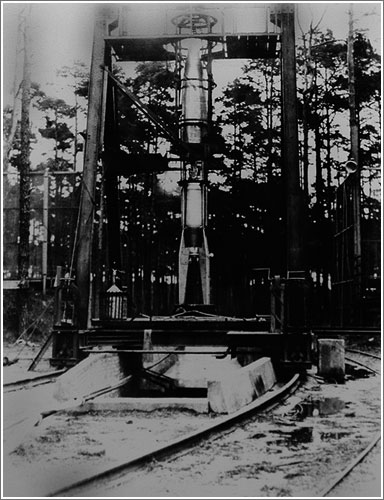

The A-3 rocket at the static test stand in Kummersdorf.

Rockets had been used on both sides during World War I. Afterward, the Allied victors lost interest, focusing research efforts on tanks, planes, and other somewhat successful weapons from the war. Germany, however, continued to pursue rocket research. The Verein fur Raumschiffahrt (Society for Space Travel) was established in 1927 in Breslau. The first successful rocket test took place in 1930, with other tests following, but by 1934 the amateur society was defunct. The German army took over rocket-testing, consistent with its practice from the 1920s of working illegally with Russia on weapons research. The army sought a better artillery weapon, so the research was in the ordnance department.

In 1932, Wernher von Braun joined army rocket research at Kummersdorf. The first test of a 650-pound/thrust motor fueled with alcohol and liquid oxygen fed into the combustion chamber by nitrogen failed when the engine blew up. Undaunted, von Braun and staff designed the Aggregate 1 (A-1) rocket.

The A-1 was approximately 4.5 feet long with a 1-foot diameter and a takeoff weight of 330 pounds. The engine developed 650 pounds of thrust for 16 seconds. Stabilization was built in as a design factor. The nose of the rocket spun, serving as a gyroscope; before launch, an electric motor revved it to 9,000 rpm, and it ran down during flight. The first three A-1 tests at Kummersdorf failed.

Even before the first A-1 test, the A-2 was designed with the same 650-pound/thrust engine but separate fuel and liquid oxygen tanks with a gyroscope in the middle close to the rocket’s center of gravity.A-2 tests relocated from Kummersdorf to preserve secrecy (by this time the Nazis were in power and suppressing information and amateurs). Von Braun’s 1934 Ph.D. thesis referred to his work as “combustion experiments.”

In December 1934, two A-2s were launched successfully at Borkum (and were named Max and Moritz, the Katzenjammer Kids) from a 40-foot launch platform. They attained 1.4 miles of altitude and landed, with a parachute assist, approximately 800 meters from the launchpoint. When the army asked him about the weapon potential of the A-2, von Braun noted that conventional artillery had the same capability.

In March 1935, Hitler repudiated the Versailles Treaty, and the buildup was on. Kummersdorf was renamed Experimental Station West. The A-3 was on the drawing board, and the Army Ordnance Office began a cooperative effort with the Luftwaffe that eventuated in the special-weapons development center at Peenemünde.

Peenemünde was in northern Usedom. Its conversion to a test center began in 1936.By 1937, the Kummersdorf contingent could relocate all their work, except for engines, which remained at Kummersdorf until 1940. Peenemünde provided a clear, 300-kilometer firing range, harbors, and all other required facilities. Most noteworthy was its supersonic wind tunnel, which initially was smaller than the one at Aachen that tested up to Mach 3.3. By 1942, the capability of the wind tunnel at Peenemünde exceeded Mach 4.4, the best in the world until after the war. Peenemünde also had a rocket production facility.

The A-3 was 21 feet, 8 inches long, 2 feet, 4 inches in diameter; its takeoff weigh was 1,650 pounds. Inside the nose was a telemetry package to measure heat and pressure during flight. There was a guidance system to control attitude, a liquid oxygen tank and nitrogen reservoir, and a parachute container. In the rear was the 6-foot-long motor, encased in the alcohol tank, with 1.5 tons of thrust. The rocket had four fins and jet vanes in the nozzle for better early-flight control and in the thin upper atmosphere, where fins were ineffective.

The A-3 took nearly two years to build because of difficulties developing a guidance system. A combination of four gyroscopes spinning at 20,000 rpm to control yaw and pitch helped keep the rocket level. The 1937 test on the island of Greifswalder Oie failed because the gyro system couldn’t control beyond 30 degrees and couldn’t correct the A-3’s tendency to turn into the wind. Because the A-3 hadn’t burned or exploded, the group felt confident enough to develop a small A-5 to refine the new technologies. The A-4 was the designation for the military rocket that became the V-2. The V-2 became the experimental vehicle for both the United States and the Soviet Union. Von Braun led the U.S. space effort for many years.

References Johnson, David. V-1, V-2: Hitler’s Vengeance on London. New York: Stein and Day, 1981. King, Benjamin, and Timothy J. Kutta. Impact: The History of Germany’s V-Weapons in World War II. Rockville Centre, NY: Sarpedon, 1998.