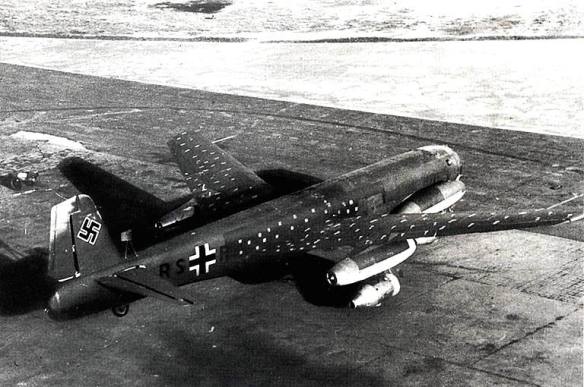

The Ju 287 project started in June 1943. The aircraft was to have had swept-back wings and four turbojets, one beneath each wing and one on either side of the forward fuselage. However, the low speed stability problems of swept wings had at that time not been solved, so in order to retain the high-speed capabilities of sweep, while at the same time avoiding low-speed stalls, the designers compromised by giving the wings 25 degrees of forward sweep. The wings were attached to the fuselage at about its midpoint, giving the aircraft the appearance of having an exaggeratedly long nose.

Flight tests began on 16 August 1944 (pilot: Siegfried Holzbaur), with the aircraft displaying extremely good handling characteristics, as well as revealing some of the problems of the forward-swept wing under some flight conditions. The most notable of these drawbacks was ‘wing warping’, or excessive inflight flexing of the main spar and wing assembly. Tests suggested that the warping problem would be eliminated by concentrating greater engine mass under the wings. This technical improvement would be incorporated in the subsequent prototypes. The 287 was intended to be powered by four Heinkel-Hirth HeS 011 engines, but because of the development problems experienced with that engine, the BMW 003 was selected in its place. The second and third prototypes, V2 and V3, were to have employed six of these engines, in a triple cluster under each wing. Both were to feature the all-new fuselage and tail design intended for the production bomber, the Ju 287A-1. V3 was to have served as the pre-production template, carrying defensive armament, a pressurised cockpit and full operational equipment.

Work on the Ju 287 programme, along with all other pending German bomber projects (including Junkers’ other ongoing heavy bomber design, the piston-engined Ju 488) came to a halt in July 1944, but Junkers was allowed to go forward with the flight testing regime on the V1 prototype. The wing section for the V2 had been completed by that time. Seventeen test flights were undertaken in total, which passed without notable incident. Minor problems, however, did arise with the turbojet engines and the RATO booster units, which proved to be unreliable over sustained periods. This initial test phase was designed purely to assess the low-speed handling qualities of the forward-swept wing, but despite this the V1 was dived at full jet power on at least one occasion, attaining a speed in the medium dive-angle employed of 660kph. To gain data on airflow patterns, small woolen tufts were glued to the airframe and the “behavior” of these tufts during flight was captured by a cine camera mounted on a sturdy tripod directly ahead of the plane’s tailfin. After the seventeenth and last flight in late autumn of 1944, the V1 was placed in storage and the Ju 287 programme came to what was then believed to be its end. However, in March 1945, for reasons that are not entirely clear, the 287 programme was restarted, with the RLM issuing a requirement for mass production of the jet bomber (100 airframes a month) as soon as possible. The V1 prototype was taken out of storage and transferred to the Luftwaffe evaluation centre at Rechlin, but was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid before it could take to the air again. Construction on the V2 and V3 prototypes was resumed at the Junkers factory near Leipzig, and intended future variant designs (meant for service in 1946) were dusted off. These included the Ju 287B-1, seeing a return to the original powerplant choice of four 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) thrust HeS 011 turbojets; and the B-2, which was to have employed two 3,500 kg (7,700 lb) thrust BMW 018 turbofans. While the Heinkel turbojet was in the pre-production phase at war’s end, work on BMW’s radical and massively powerful turbine engine never proceeded past the blueprint stage. The final Ju 287 variant design to be mooted was a Mistel combination-plane ground attack version, comprising an unmanned explosives-packed “drone” 287 and a manned Me 262 fighter attached to the top of the bomber by a strut assembly. The cockpit of the 287 would be replaced by a massive impact-fused warhead. Takeoff and flight control of the combination would be under the direction of the 262’s pilot. The 262 would disengage from the 287 drone as the Mistel neared its target, the pilot of the fighter remotely steering the 287 for the terminal phase of its strike mission.

The Junkers factory building the V2 and V3 was overrun by the Red Army in late April 1945; at that time, the V2 was 80% complete, and construction of the V3 had just begun. Wocke and his staff, along with the two incomplete prototypes, were taken to the Soviet Union. There, the third prototype (returned to its original Junkers in-house designation, EF 131) was eventually finished and flown on 23 May 1947, but by that time, jet development had already overtaken the Ju 287. A final much-enlarged derivative, the EF 140, was tested in prototype form in 1949 but soon abandoned.

Perhaps the alternative term frequently used in Germany at the time – Wunderwaffen – comes closer to defining the true nature of these secret devices, for they were often truly things of wonder, being either completely new and hitherto undreamed-of outside a small select group, or achieving previously unthinkable levels of performance thanks to breakthrough innovations in science and technology. Some of them, it is true, were ‘ideas whose time had come’, in that the basic principle was understood, but had not yet been successfully applied, and in these cases, teams of scientists and engineers in America, Britain and Germany (and sometimes elsewhere: there were several significant advances made by Italy) were engaged in a headlong race to get the first reliable working version onto the battlefield. The development of the jet aircraft and of radar, not to mention the development of nuclear fission, stand out amongst those. But in other areas, particularly in rocketry and the invention and perfection of the all-important guidance systems, Germany stood head and shoulders above the rest. Her scientists made an enormous and outstanding contribution, not just to the German war effort, but to modern civilisation. However, there were areas where German science and technology were deficient, most importantly – arguably – in the field of electronic computing machines, which were not weapons themselves but something without which the bounds of technological development would soon be reached. However, all too often these deficiencies arose as a result of demand chasing insufficient resource, and time simply ran out for the scientists of the Third Reich before a satisfactory result could be produced.

TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

Time and again in the course of this work we will come upon development programmes which were either cancelled before they came to fruition or which were still in progress at the war’s end. Many of them, of course, did not get under way until 1944, when the spectre of defeat was already looming large in Berlin and many essential items were in increasingly short supply. We can only speculate upon the possible outcome of an earlier start on the course of the conflict. Others were cancelled simply because they did not appear to offer the likelihood of spectacular results, and in those cases we can, all too often, detect the hand of Adolf Hitler. In general, we can note what can only be described as a wrong-headed insistence on his part that big (and powerful) was always beautiful (and irresistible). This major flaw led him to push for the development of weapons such as the fearsome – but only marginally effective and very expensive – PzKpfw VI Tiger and King Tiger tanks, which would have been far better consigned to the wastebin from the very outset, and the resources squandered upon producing them – and then keeping them in service – redirected into more appropriate channels such as the more practical PzKpfw V Panther.

In a very real sense, Hitler himself motivated and ran the German secret weapons programme. There seems to be a direct and very tangible link between this programme and his psyche, and we are perhaps left wondering whether the Wunderwaffen would have existed without him. On balance, it seems certain that they would have done, given the creative imagination of so many German scientists and the readiness of many of her military men to accept innovation, but it is equally certain that without Hitler’s insistence, many weapons systems which made a very real impact upon the course of the war would either not have been developed at all, or would, at best, have been less prominent.

Nonetheless, without the genius of many German scientists and the brilliance of German technologists and engineers, the entire programme would have been stillborn. Many of the weapons produced for the first time in Germany and employed in World War II went on to become accepted and very important parts of the broader armoury, and several have made an enormous impact on life as a whole outside the military arena. The more spectacular failures have a certain grandeur, despite their shortcomings, and even the outright myths – and there were many, some remarkably persistent – frequently had an underpinning of fact.