Archery (kyudo; literally “the way of the bow”) was the weapon most closely associated with warriors and was in common use by the end of the prehistoric era, during the fourth or fifth centuries C.E. While the term kyudo is more common today, kyujutsu (“technique of the bow”) was used to describe archery in the age of the samurai.

Warriors practiced several types of archery, according to changes in weaponry and the role of the military in different periods. Mounted archery, also known as military archery, was the most prized of warrior skills and was practiced consistently by professional soldiers from the outset in Japan. Different procedures were followed that distinguished archery intended as warrior training from contests or religious practices in which form and formality were of primary importance. Civil archery entailed shooting from a standing position, and emphasis was placed upon form rather than meeting a target accurately. By far the most common type of archery in Japan, civil or civilian archery contests did not provide sufficient preparation for battle, and remained largely ceremonial. By contrast, military training entailed mounted maneuvers in which infantry troops with bow and arrow supported equestrian archers. Mock battles were staged, sometimes as a show of force to dissuade enemy forces from attacking. While early medieval warfare often began with a formalized archery contest between commanders, deployment of firearms and the constant warfare of the 15th and 16th centuries ultimately led to the decline of archery in battle. In the Edo period archery was considered an art, and members of the warrior classes participated in archery contests that venerated this technique as the most favored weapon of the samurai.

In the earliest Japanese literary sources, military figures relied upon horse and arrow. Yet in the popular imagination, the samurai is always linked with the sword. In fact, swords were an important symbol of samurai status, particularly during the Edo period and afterward. However, as the warrior tradition began to develop, the most important weapon was the bow. The classic image of a medieval warrior with a long bow astride a dashing stallion does not accurately describe the typical soldier of the Heian through late Kamakura periods. However, many high-ranking samurai and those employed by wealthy domain owners were known for their equestrian archery skills. By the 14th century, as armies increased in size and outfitting sizable battalions became costly, even foot soldiers (ashigaru) were equipped with the relatively inexpensive bow and arrow, thus shattering the legendary exclusivity of warrior arts as “the way of the bow and horse.” Nonetheless, in the middle years of the feudal period, the bow gradually declined in prominence, with foot soldiers preferring to use naginata, a polearm with a curved blade, and then the straight spear (yari) after about 1450 C.E. The firearm eventually displaced archery in the arsenals of most samurai in the late 16th century. Thereafter, samurai continued to practice archery, though mostly as a spiritual and physical discipline and a popular form of entertainment, rather than as a martial skill for practical use.

Most ranking warriors carried several weapons in addition to their bows and arrows, one of which was a sword. Considered a viable defense only in hand-to-hand combat, the sword had disadvantages, such as fairly common concerns like broken blades or the prospect of complete loss if the weapon was lodged firmly in a corpse. Further, swords had symbolic associations with divinity and elite warriors, and were expensive and difficult to obtain for average samurai of low or middle rank. By contrast, arrows were plentiful, easily replaced, and more reliable. Thus, among the many military arts listed above, archery remained the traditional samurai specialty, although medieval Japanese swords were considerably more refined than those made in medieval Europe, where the sword was the weapon of choice. Foot soldiers, often excluded from the ranks of true samurai, were more likely to utilize polearms and spears.

Archery was widely regarded as the best way to ascertain a warrior’s abilities. In many military tales, samurai skills were assessed by the length of arrow (measured in fists or hand-widths) used to strike a target from a moving horse. Battles were occasionally settled not by entire armies but through a mounted archery duel performed by samurai leaders. Opponents would aim arrows while riding toward each other, using one arrow for each pass. Several passes might be used to determine the victor, rather than fighting until death of one party. Usually, fatal wounds were inflicted only after soldiers fired several arrows, not because their aim was poor, but rather because Japanese armor was skillfully designed to deflect such blows.

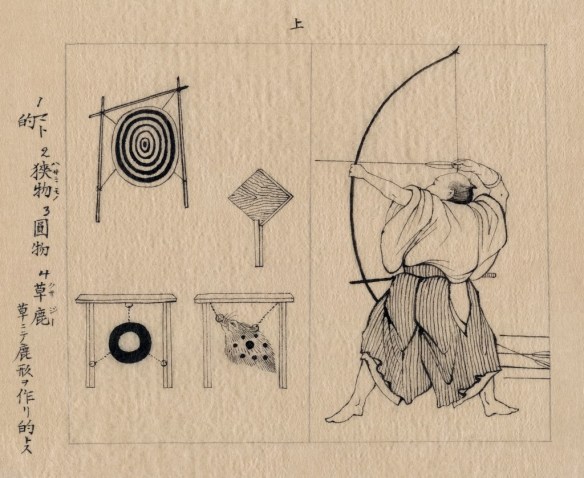

Typical samurai bows measured from about five feet long to more than eight feet, and about two-thirds of the bow was situated above the hand grip. These are generally classified as longbows, although they differ in form from similar weapons called longbows used in medieval European warfare. Japanese wooden bows had to be long to generate the power to launch arrows while remaining flexible and strong, since laminated wood and composite materials could separate if flexed strenuously. Handgrips placed in the center of such long bows would have made equestrian archery impossible, and would not have balanced the elasticity of the upper portion of the bow. Therefore, the handgrip was placed off-center, producing bows that bent in an asymmetrical fashion, which facilitated drawing the bow, reduced stress on the bent wood, and made mounted archery possible for those who were well trained. Less-experienced archers such as foot soldiers often used bows that were shorter and easier to manipulate. However, the Chronicle of the Wei Dynasty (Weizhi) notes that Chinese envoys saw Japanese archers using bows with shorter lower portions and longer upper sections by the mid-third century, although there is no mention of equestrian practices at the time.

From the Kamakura period, bows were constructed in layers utilizing bamboo slats for added strength and flexibility. The core of the bow was made of stiff wood and was combined with laminated pieces of bamboo. After the 15th century, the sides of the bow were laminated with bamboo slats, and the wooden core of the bow was thus completely encased in bamboo. For added strength, cane was wound around the stave of the bow. While in theory the cane bow was finished with lacquer for additional protection, this was not always the case in practice.

There were numerous kinds of arrows and arrowheads, intended to perform specific functions based on the desired point of contact. The average arrows were about 12 fists in length, although both longer and shorter arrows survive. Arrow length depended upon the skill of the archer and the desired target. During the medieval era, most samurai favored arrows between 86 and 96 centimeters (about 34–38 inches) in length. Arrow shafts were made of bamboo harvested in early winter and shaved to remove the outer bark and joint nodes. The shaft was straightened and softened by placing it in hot sand.

Arrowheads were fastened to the shafts by a system of flanges similar to the tangs seen on swords. These arrows had three or four fletchings made from the wing or tail feathers of varied species of bird. The shaft of the arrow was fashioned from young bamboo. In the early medieval period, arrow shafts were carried in devices called ebira, which resembled a woven chair. These quivers were worn on the hip and made from pieces of woven wood. Later, quivers called utsubo were used, which were wood, covered in fur, and worn across the back. Like other military equipment, the various components used by archers were manufactured and distributed in various locations, but the shapes and styles of these tools of war were quite consistent throughout medieval and early modern times, and across all regions of Japan.

Some forms of archery practiced in Japan were not intended to serve as preparation for battle. Mounted archery was ritualized in Japan beginning in the early 11th century with the practice called yabusame. Often performed for emperors or shoguns to glorify military training and celebrate samurai achievements, this ceremonial pastime involved four distinct movements. The designated primary archer first pointed a drawn arrow at the sky, and then the ground, to symbolize harmony between heaven and earth. Mounted archers would then begin to shoot at targets two meters away composed of five concentric circles in multiple hues. These targets were about 60 meters apart with a surface area of 60 square centimeters, and the archers aimed as they rode their horses at full gallop around a track. In the third movement, soldiers who had struck all three targets were invited to aim at three clay targets that were about one-third the size of targets in the second movement. Finally, the primary archer inspected all of the targets to determine who had demonstrated the best military prowess. Yabusame is still practiced today and is seen as an enduring symbol of Japan’s traditional military arts.